hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Children of undocumented immigrants unable to access healthcare services

“I think I need to go to the hospital,” the child said. In reply, the mother simply repeated, “Let’s just wait.” The child, who was running a high temperature, pressed again to go to the hospital; the mother shook her head. “Does it hurt a lot? You don’t need to go to the hospital,” she said soothingly. The mother, who is from Peru, is an undocumented immigrant. Since she cannot receive health insurance benefits, medical costs make a trip to the hospital unthinkable.

Another child whose Vietnamese parents are both undocumented has never been to the dentist despite having nine cavities. “It’s really expensive,” the child explained. “I’d like to go to one of the big hospitals for a checkup, but we can’t go because we don’t have insurance.”

These are the children of undocumented migrants. Because their parents are in South Korea illegally, their births have not been reported. Not being registered anywhere, they are not entitled to health insurance benefits. Even though they were born and have lived their whole lives in South Korea, the lack of any birth record means there is effectively no trace of them. They can attend elementary and middle school thanks to a 2010 amendment of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act enforcement decree, but many still cannot go to the hospital when they are sick.

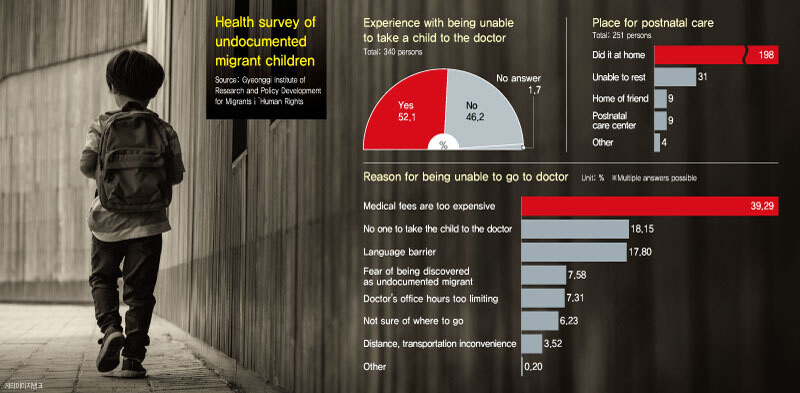

On Nov. 6, the Hankyoreh acquired the final report from the “2019 survey of health rights support for unregistered migrant children in Gyeonggi Province” by the Gyeonggi Institute of Research and Policy Development for Migrants’ Human Rights (GMHR). The results showed one out of every two married couples with an undocumented migrant child under 18 in Gyeonggi Province was unable to take the child to the hospital when sick. When asked whether they had the experience of not taking a child to hospital when he or she was sick, 177 out of 340 respondents (52.1%) answered “yes.” This means a 52.1% rate of “unmet health care needs,” referring to the percentage of people unable to visit hospitals or clinics despite having a health condition.

The number is nearly 10 times higher than the 5.6% rate of unmet health care needs reported in 2006 for South Korean children aged 12 to 18 according to the government’s seventh national health and nutrition survey. While five in 100 South Korean children are unable to visit the hospital when sick, the rate for undocumented migrant children climbs all the way to 52 in 100. Among 123 guardians with a child complaining of toothache, 47% (50) said they had been unable to take the child to a dentist.

When asked for their reason(s) for not taking their child(ren) to the hospital, 39.3% of respondents said, “Because it’s too expensive,” while 18.2% said, “Because we don’t have anyone to take the child to the hospital.”

Over the past year, the GMHR held interviews with 340 illegal migrant residents in Gyeonggi Province to investigate their situation. This kind of large-scale survey on the health rights of undocumented migrant children by a local government is rare.

With parents carrying the illegal resident “scarlet letter” around after arriving in search of the “Korean dream” while their children go without proper healthcare benefits, many observers are arguing that support should at least be provided for children’s healthcare. In its report, GMHR said, “The examples of education rights being guaranteed regardless of students’ sojourn status for compulsory elementary and middle school education, as well as inclusion [of unregistered students] as beneficiaries of School Safety and Insurance Association support, should be consulted in considering plans for bringing unregistered migrant children into health care administration services independently without a process of conferring citizenship or sojourn status upon them.”

Objections have been strong. Perhaps the most common complaint is that guarantees on undocumented children’s health rights will merely lead to more people staying illegally. But others are strongly pointing to a growing trend in Europe and elsewhere around the world of guaranteeing health rates on par with ordinary citizens to illegal sojourners and their family members (particularly pregnant women and children) since the adoption of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which stipulates health rates for all children as a basic survival right.

“In the US state of California, healthcare services have been provided even to undocumented residents not only because of the belief that health rights should be a basic right guaranteed for all, but also because it ultimately reduces the burden on the public health budget and because migrant children need to grow up healthy to be able to enter the labor market normally,” explained attorney Lee Taek-geon.

“If we consider that South Korea is a society that already has over two million migrants living in it, providing suitable healthcare services to their children is not merely morally right but also proper in policy terms,” Lee said.

By Hong Yong-duk, South Gyeonggi correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 4Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 7OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 8Inside the law for a special counsel probe over a Korean Marine’s death

- 9Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 10[Exclusive] Hanshin University deported 22 Uzbeks in manner that felt like abduction, students say