hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] Plans for Korea’s lunar orbiter were unrealistic and poorly conceived from the start

Four years after South Korea started preparing to put a probe into lunar orbit, the project’s basic plan has yet to be finalized, and now the orbiter project has run into opposition from NASA, the government’s key partner in the project. The central cause for these hiccups, sources say, is the unilateral attitude that the government and the Korea Aerospace Research Institute (KARI) have shown over the course of the project. According to critics, the government set the main objectives for the project without objectively assessing the level of domestic technology or adequately consulting researchers on the ground and made the situation even worse by patching over problems instead of reassessing the overall plan.

During the presidencies of Roh Moo-hyun and Lee Myung-bak, the lunar orbiter project was only a distant research goal, slated for launch in 2020 under Roh and 2023 under Lee. But that situation changed after the election of Park Geun-hye as South Korean president in December 2012: during a televised presidential debate, Park declared that the Korean flag would fly on the moon in 2020. The lunar orbiter project was named one of Park’s key objectives in May 2013, three months after her inauguration, and unrealistic goals were set for the project: the orbiter development period was shrunk to three years (2015-2017).

“Even a satellite that’s going to be orbiting the earth takes four or five years to develop, so it was nonsense to think we could develop a satellite to orbit the moon in just three years. The project got off on the wrong foot,” a senior KARI official who is familiar with the project’s history told the Hankyoreh over the phone.

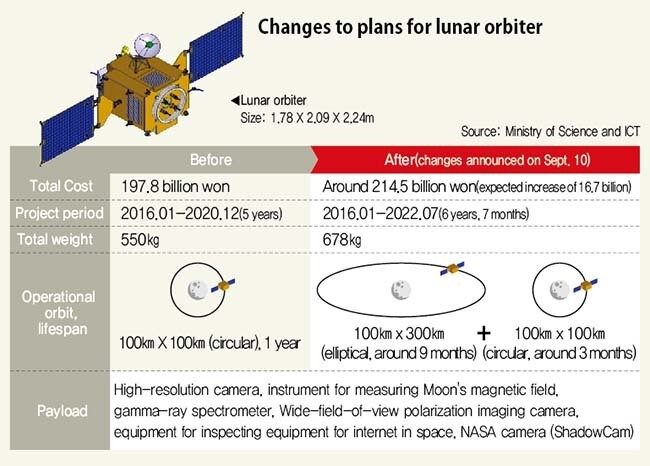

After that, the main aspects of the project were decided and altered regardless of the level of domestic technology required or the opinions of researchers who were actually working on the project. In September 2014, a plan to operate a lunar orbiter with a total weight of 550kg carrying four payloads (cameras and other lunar exploration equipment) for one year in a circular orbit at a 100km elevation above the moon passed a preliminary feasibility assessment by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MOEF). In January 2016, a basic lunar exploration plan that increased the number of payloads from four to six was approved by the National Space Committee; in December, KARI and NASA concluded an agreement outlining a one-year mission in a circular orbit. In exchange for NASA facilitating deep space communication, South Korea agreed to add a NASA camera (called ShadowCam) to the lunar orbiter.

Researchers on KARI’s lunar exploration project team described proposed alterations to the project mission – which didn’t reflect the opinions of technicians on the ground – as unrealistic from the very outset. “They never bothered to examine the various parts, equipment, number of payloads, or necessary amount of fuel when calculating the orbiter’s target weight,” said “N,” a researcher on the team.

“All we were told was that, since the Korean-made rocket that will power the second-stage lunar lander [after the moon orbiter project] can only transfer up to 550kg to the moon, we should stick to the 550kg limit for the first-stage lunar orbiter as well,” even though that’s supposed to be powered by an American-made rocket.

Weight never complied with 550kg limit even onceThe weight of the planned orbiter continued to increase, without complying with the 550kg limit even once: 610kg in September 2018, 638-662kg in March 2019, and 678kg more recently. In order to complete the same mission in one year with a heavier probe, the lunar orbit would have to be elliptical, rather than circular, which is what the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) announced this past September.

The project management committee, staffed by KARI experts, concluded that the weight limitations would have to be lifted in an independent report in March. In the report, they analyzed the respective pros and cons of eight theoretical ways to resolve the shortage of fuel resulting from the increasing weight – such as making the fuel tank bigger, altering the orbital revolution, shortening the mission length, and changing course.

In its report, this committee underlined that changing the orbit and shortening the mission length would both require NASA’s consent. Nevertheless, the government and KARI announced a tentative change to an elliptical orbit at an elevation of 100-300km in September, only to run into opposition from NASA, which had never approved the change.

Opportunities to fix problems were ignored“KARI and the Ministry of Science and ICT were anxious to duck responsibility whenever a problem arose, which only exacerbated those problems,” said Lee Cheol-hui, a lawmaker with the Democratic Party.

“The saddest part of all is that even though various problems came to light [when the new administration took power], the National Space Committee only delayed the launch date [from 2018 to 2020] while keeping the other conditions in place in August 2017. Thus, it missed an opportunity to reassess the overall plan,” said “N,” the KARI researcher.

“While the Ministry of Science and ICT announced that it was removing the weight limit [capped at 678kg] this past September, we’re still going to be short on fuel because the fuel tank has already been designed. The proposed solution of changing course isn’t feasible under domestic technology, and we’re unlikely to get help from NASA because that would fall outside the scope of our agreement.”

By Choi Ha-yan, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

Most viewed articles

- 1Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 2At heart of West’s handwringing over Chinese ‘overcapacity,’ a battle to lead key future industries

- 3[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- 4Trump asks why US would defend Korea, hints at hiking Seoul’s defense cost burden

- 5Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors

- 6Fruitless Yoon-Lee summit inflames partisan tensions in Korea

- 7[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 8[Column] For K-pop idols, is all love forbidden love?

- 9[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 10[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes