hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report] South Korea’s social divide between universities within Seoul and universities without

I

In the British House of Commons, two red “sword lines” have been drawn into the floor. The lines were put there to prevent the opposing lawmakers facing each other across the floor from taking out their swords and running each other through during their arguments. It’s a symbol of the British Parliament, a setting where heated debates unfold. The reason Cho Ji-hoon, a 22-year-old university student from Gimhae, South Gyeongsang Province, chose political science and international relations as a major was because he wanted to pursue that same kind of heated politics in South Korea.

The first thing Cho learned in college was self-deprecation: “Universities fall as cherry blossoms bloom.” The professors at the university Cho attends predicted that universities far away from Seoul would soon start dying off one by one. Cho was simply born in Gimhae, his parents’ parents’ parents’ hometown, and he simply attends school there -- but others tend to judge him on those two factors alone. Every time he tries to estimate his future, he describes it as being “bleak like facing a backlog of laundry.”

“In our department, a good outcome is getting a job at a bank,” he said. “When I look at my older classmates who’ve gotten jobs, they’re typically making about 1.8 to 2.5 million won [US$1,513-2,101] a month. It’s very tough to find anything that pays more than 2.5 million.”

“I’m probably going to pick a job with no money in it, and when I put the numbers in my calculator, all I can think is, ‘How am I going to survive?’”

Cho’s parents divorced when he was in his second year of high school. His father’s business went under, and after the divorce his mother, who works as an insurance broker, assumed his debts. After finishing with his rolling admission screening in his third year, Cho worked nonstop -- at a convenience store, a family restaurant, a chemical plant, a hotel, and a barbecue restaurant. He now works at a fast food place five to six hours a day, three to four days a week. When asked whether he wished for some kind of economic support, he said, “That’s like saying that if Goguryeo had unified the Three Kingdoms, Manchuria would belong to Korea today -- it's meaningless. I’m very tired physically, but all I can do is the best I can in my given circumstances.”

Cho defined himself as “someone outside the mainstream.” He did not take sides in the debate that unfolded after allegations of “résumé swapping” involving the daughter of former Justice Minister Cho Kuk.

“I didn’t agree with Cho Kuk’s family, but I didn’t agree with the Seoul National University students’ demonstrations either. There have also been questions over whether the commendation Cho’s daughter got from Dongyang University helped her get into her school -- but there’s a disparaging undercurrent toward local universities when people say things like that. I think this deep-seated academic cliquism needs to be resolved. Fairness is when Cho Ji-hoon, someone who ranked third or fourth in his class in high school, can hope to succeed if he works hard at a local private university. What isn’t fair is when everything is determined by the name of your university.”

Cho’s reality has been weighing heavily on his beliefs.

“My friends keep telling me to transfer to a university in Seoul. But if we all go to Seoul, what happens to the provinces? I felt that people like me should work to create livable neighborhoods [outside Seoul]. But as I’ve heard so many people urging me to transfer, I’ve started to panic.”

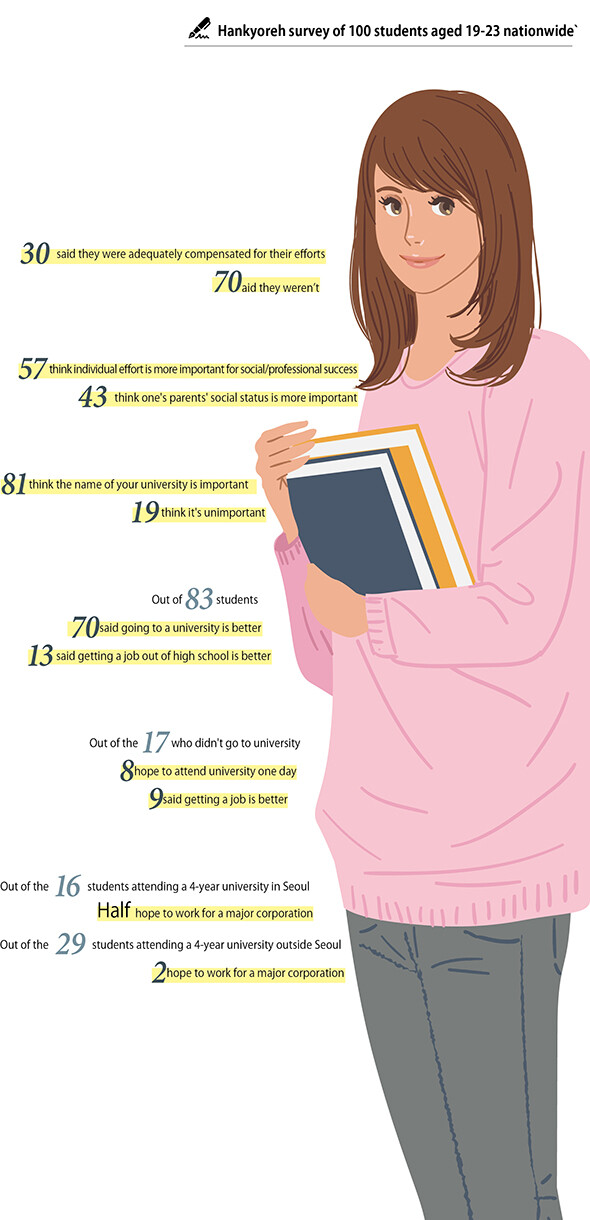

Majority of students in provincial universities want to moveOut of 47 students from universities outside the Greater Seoul area who spoke to the Hankyoreh, 26 of them -- 55% -- wanted to leave the region where they currently live. The percentage is 2.5 times higher than the eight out of 36 students (22%) at junior or four-year universities in the Seoul area who said they wanted to leave their region. Many students at local universities are like Cho Ji-hoon’s friends -- regarding a transfer as their route to survival. The reason given by local students for wanting to leave was the “lack of opportunities.” Gang Eun-bi (pseudonym), 21, a student at a four-year university in Daegu, said, “There just aren’t many companies where you can get a job. You have to go to Seoul.”

The learning environment in the provinces is also less than satisfactory. Kim Tae-gwang, 25, a graduate of a North Gyeongsang Province university, hoped to become an actor. But there was nowhere to study acting in his hometown of Changwon, South Gyeongsang Province, or even in the province where his university is. In December 2016, he left for Seoul, where he attended an acting academy in the city’s Cheongdam neighborhood while working part-time as a restaurant server. But he ended up going back to his hometown after being diagnosed with depression due to stress over living and study costs. After his return, he gave up on his acting dreams. But he still contacts his former acting instructor when he has questions about something. In Seoul, there had always been acting instructors available -- but the closest to Changwon was in Busan, about 50km away. Even his friends were split into two groups: “In Seoul, I had the friends I could share my pastimes and values with, and at home I had only the friends left that I could share memories with.”

It isn’t only students outside of Seoul who feel discriminated against and isolated. Junior college students find themselves suffering the same plight. Article 27 of the Higher Education Act states that the purpose of junior colleges is to “cultivate professionals.” It’s a distinct role from that of universities, which are defined by Article 28 as being intended to “teach and research profound theory and [. . .] application methods.” But with their different establishment goals, junior colleges have been shunted to the very bottom by a hierarchy-obsessed society. Gong Min-jeong (pseudonym), 23, a graduate of a South Jeolla Province junior college who now works as a medical technician at a general hospital in the same region, suffered a scarring experience. She previously trained at “K” university hospital in Seoul. One day, she was with some of her fellow trainees at a pub when she ran into some other trainees. Gong’s group was made up entirely of local junior college graduates, while the others they met were students of K University. Only later on did she learn that it was a drinking party organized by the instructor exclusively for K University students. The discrimination carried over into her workplace.

“People who work at our hospital who graduated from four-year university often have people tell them, ‘Why are you working here? You should go someplace better.’ But they never say things like that to the junior college graduates. It’s a subtle kind of insult.”

The Hankyoreh asked 83 university students to rate their satisfaction with their school experience on a 10-point scale. The results showed an average of 7.5 points for students in the Greater Seoul area, 6.8 points for university students outside Seoul, and 5.3 points for junior college students. Kim Su-jeong (pseudonym), 20, a student at a Greater Seoul-area junior college, rated her experience as a student a “2.” The school did not seem to have any concerns about teaching the students properly, she explained. Lectures were of poor quality, and rumors circulated about professors embezzling money from the school. Even the professors would openly tell the students, “You should transfer.” When asked to rate out of 10 points how important academic cliques were in South Korean society, Kim answered “10” without any hesitation.

“The school you attended is important, you know? Whenever people meet you, they always ask, ‘What school did you go to?’” she said.

If there only 100 South Koreans aged 19 to 23, 67 of them would be attending a junior college or a provincial university outside of the Greater Seoul area. But these students did not perceive themselves as representing a “majority” or the “mainstream.”

Students content with living outside the mainstreamYoung people in regions outside of Seoul did not see themselves as necessarily having to become mainstream. Many expect that their future will be better than their present. One of these is Shin Myeong-gwan, 19, a student in the hotel/tourism/barista department at Masan University in South Gyeongsang Province. Shin rated his satisfaction with his student experience an “8.” His dreams of becoming a professional barista began in middle school when he learned to make hand-drip and siphon coffee. “I studied specifically to get into this [university],” he said. Though still a freshman, he has already acquired Level 1 and 2 barista certification and trainer certification. Throughout the interview, he appeared cheerful as he talked about his hopes of working as a barista at an overseas hotel. Chae Yu-ri (pseudonym), 21, a student at a four-year university in Gyeonggi Province, attended an alternative school for her middle school studies before dropping out to pursue music. Later deciding that she wanted to go to college, she attended an academy for students retaking the college entrance exam, and she ended up at her current university. Chae rated her satisfaction with university life a “10.”

“Attending school after not attending for so long, I’ve found it enjoyable simply learning things,” she said. “It’s the first time people have asked me what I think, and it’s been a good experience discovering my own development potential in the process.” As with many young people, her current economic situation is tight. “I’m living on 500,000 won [US$420.31] a month,” she said. “It’s hard. A lot of people I know are also struggling with finding a job. But I believe that as I get older, I’ll continue to develop, and I’ll get more professional recognition.”

Students in provinces resigned to working for smaller companiesThis may be a form of resignation. Bae Yoon-jeong, 20, a student at an Incheon junior college, believes her future will improve at some point despite her poor school environment. Like fellow junior college student Kim Su-jeong, Bae feels like she isn’t learning anything at her school, but she forgets about the reality when she imagines her future after finding a job.

“Apart from the personal relationships, there isn’t anything about the school I find satisfactory,” she said. “With a lot of classes, I have no idea why I’m taking them. But I think I’ll acquire a lot of things once I find a job. I may not go straight into a big company, but I think different opportunities will open up as I build up experience at the lower levels. I’m looking into small and medium-sized companies where I can develop sales or marketing strategies.”

Of the 29 students at private universities outside of Seoul who spoke to the Hankyoreh, only two said they hoped to work for a major company. Nine said they aspired to a job at a small company. Of the 28 junior college students, just two said they wanted to go to work for a large company; 11 said they wanted to work for a small company. Three of 10 provincial public university students said they wanted a job at a major company. In contrast, not a single one of the 16 students from Seoul-area universities said they wanted to work at a small company. Eight of them, or half, hoped to find a job at a large company. This could be taken as a sign of entrenched discrimination -- but it could also be that some of them, in their resignation, hope to turn their present into a somewhat better future.

If the House of Commons “sword line” divides right from left, then the boundaries of Seoul and the “four-year university” threshold divided South Korea’s young people into “top” and “bottom.” At every moment in life, South Korean society questions, “Why haven’t you crossed that line?” With the discrimination so firmly rooted, what the young people living in South Korea today need to overcome their struggles is not a society that tests them at every second, but one that supports them in achieving a life of equality.

By Kim Yoon-ju, Hyu-yun, Kang Jae-gu, and Seo Hye-mi, staff reporters

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 3Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 4Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 5[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 6Historic court ruling recognizes Korean state culpability for massacre in Vietnam

- 7Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 8Story of massacre victim’s court victory could open minds of Vietnamese to Korea, says documentarian

- 9Historic verdict on Korean culpability for Vietnam War massacres now available in English, Vietnames

- 10[Guest essay] How Korea must answer for its crimes in Vietnam