hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

S. Korean parents under 24 face economic difficulties and social prejudice

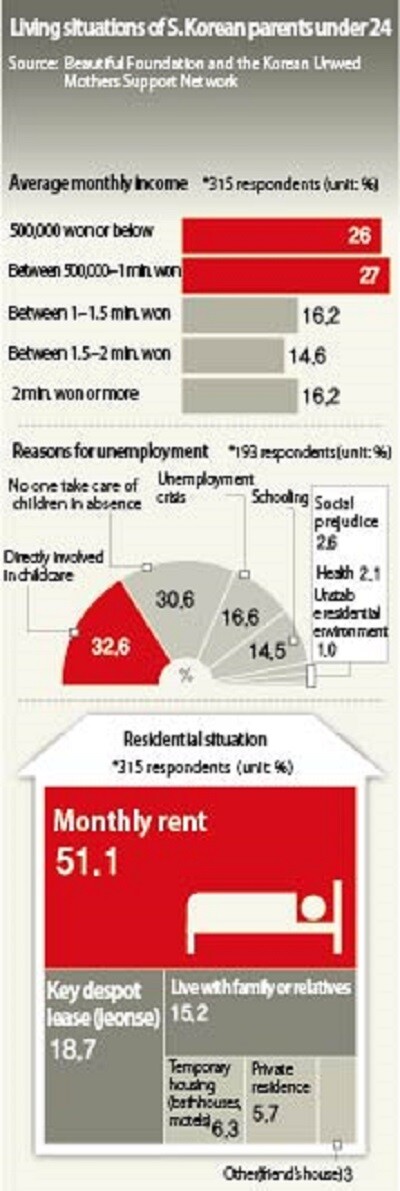

Economic difficulties, residential worries, and societal prejudice -- young parents face problems from three different angles in their attempts to bear and raise children amid their straitened circumstances. One in four young parents earns less than 500,000 won (US$432.65) a month, while many young pregnant women are forced to adopt temporary accommodations in bathhouses and motels due to a lack of suitable places to live. Five out of 10 young parents also report suffering prejudicial treatment from family members and society at large, including abandonment and recommendations to abort their child or give it up for adoption. A vivid portrait of the situation was painted in the findings of a research report on young parents acquired by the Hankyoreh on Jan. 12. The report in question was based on interviews and questionnaires administered to 315 parents under 24 (average age 18.7 years) by the Beautiful Foundation and the Korean Unwed Mothers Support Network.

Economic struggles

According to the findings reported in the study of young parents, over half of respondents (53%) reported a monthly income averaging below 1 million won (US$865.31), which included their own and their spouse’s salaries, government subsidies, and family support. A total of 26% (82 people) said they were earning 500,000 won a month or less. This contrasts with the 2.63 million won (US$2,274) average monthly income for a single-person working urban household between the first and third quarters of last year.

In most cases, young parents mostly face economic troubles because their situations often oblige them into positions of manual labor, short-term sales gigs, and other unstable forms of employment. When the 315 respondents were asked about their work history (multiple responses allowed), 56.5% reported forms of simple labor such as restaurant serving and part-time employment at coffee houses.

“I work a part-time hourly position at a fast food restaurant, but it isn’t suited at all [to raising a child] because it doesn’t really have a fixed finishing time,” said a 24-year-old surnamed Ahn who is raising a five-year-old child.

Even those uncertain, short-term positions can be too much for young parents who have to contend with child-raising responsibilities. Sixty-one percent (193) of the 315 respondents were unemployed at the time of the survey. As reasons for this, 32.6% (63) said they “wanted to be directly involved” in raising their child, while 30.6% (59) said they had no one to look after their children while they worked. When asked about their own parents’ financial situation, 64.8% of respondents reported being unable to turn to their parents for help: 24.8% described their parents as “somewhat struggling financially,” 20% as “basic livelihood security recipients” and 20% as “financially struggling but not eligible for basic livelihood security.”

Despite their dire needs, young parents found the barriers to government assistance daunting. With no separate system in place to support young parents, those hoping to receive government subsidies must be recognized as eligible for either basic livelihood security or single-parent household assistance. To receive livelihood benefits, an applicant must be making less than 30% of the median income -- 520,000 won (US$449.76) a month for a single-person household, 890,000 won (US$769.72) a month for a two-person household. For a young parent who is still a minor to be ruled eligible for basic livelihood security benefits, they must prove that their parents do not have the ability to provide support as mandated by the law. Because young parents are frequently shunned by their parents, they have difficulty providing documentation to neighborhood centers and other office regarding their parents’ inability to offer support.

Single parents are entitled to receive 350,000 won (US$302.70) a month per child toward child-raising costs and a self-sufficiency encouragement allowance of 100,000 won (US$86.49) a month. They are also eligible to live in residential facilities for single-parent families. But young parents who are in a common-law marriages are not legally recognized as single parents. This is one of the reasons that many young parents in common-law marriages do not report their marital status, even after they reach the age of 19 and are able to marry without their parents’ consent.

Unstable residential situationsWith livelihoods uncertain, residential situations were inevitably precarious. A whopping 51.1% of the young parents surveyed (161 people) were currently living under monthly rental arrangements. 18.7% (59) had paid key money deposits, while 15.2% (48) were living with family. A total of 6.3% (20) were using temporary accommodations such as bathhouses or motels. When asked about their experiences with housing during pregnancy and childbirth, a substantial number of young parents reported living in inns/motels (26), public bathhouses (nine), or a gosiwon rental room for students (one). The risk of harm to both mother and infant is high when they live in multi-use facilities during the pregnancy and childhood periods, which demand more hygienic conditions than other times in life.

But respondents were unable to receive suitable assistance to address their residential issues. 31.4% of them (99) lived at their own parents’ or their spouse’s parents’ home immediately after childbirth, while another 13.3% (42) lived in a facility for unwed mothers, for a total of 44.7%. A similar trend was observed early in pregnancy and just before childbirth. For this reason, young parents talked about their longing for stable residential situations. A 22-year-old surnamed Kim, who dropped out of high school and is currently raising a four-year-old while working at a call center, explained, “My parents have lived in monthly rentals since I was young, and it was a cramped basement space that wasn’t my own home. I was envious of people living in ordinary places like ‘villas’ [small-scale apartment buildings].”

But no separate housing measures exist specifically for young parents. Those who meet the income requirements are eligible to apply for key money-based rental housing from the Korea Land and Housing Corporation (LH), but in this case they would have to pay a rental deposit equivalent to 5% of the loan amount; a person taking out a loan of 120 million won (US$103,763) would be required to pay 6 million won (US$5,188). That may not be a huge burden for an adult worker, but it is a lot to ask from a young parent. Yu Mi-suk, a team director with the Korean Unwed Mothers Support Network, said, “We need to change the current approach by substantially lowering or eliminating key money deposits for young parents.”

The barrier of societal prejudiceThe biggest difficulty for young parents is the burden of social prejudice. In addition to being disregarded by society at large and their own parents and family members, young parents are also excluded from information regarding pregnancy and child care.

Among young parents surveyed, 54.3% of them (171 people) depended on internet portal sites for information about pregnancy and child care. A mere 18.7% received information through family members or neighborhood centers, while just 3.2% (10) received it through the Ministry of Health and Welfare or Ministry of Gender Equality and Family website.

A 23-year-old high school graduate surnamed Im who is raising a six-year-old child while working as a nursing assistant explained, “My child has been in the emergency room once or twice nearly every month. Every time there’s been an emergency, I’ve had a difficult time wondering how I’m supposed to care for my child.”

Chilly responses from family members and society were another big source of pain. Among respondents, 22.9% (72) were told to get an abortion when they told family members about the pregnancy; another 15.2% (48) were told to put the baby up for adoption. In 16.2% of cases (51), the young people were abandoned to handle the issue on their own. A 21-year-old surnamed Kang who had a child when she was 17 explained, “When I’ve gotten on the bus or subway with my child, I’ve heard the older women saying things like, ‘She’s so young and she has a child. What is the world coming to these days?’”

“I’ve cried a lot when that kind of thing has happened,” she said.

By Kang Jae-gu, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 5[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 8Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 9Nearly 1 in 5 N. Korean defectors say they regret coming to S. Korea

- 10Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range