hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Digitally illiterate senior citizens flock to community centers to apply for basic disaster allowance

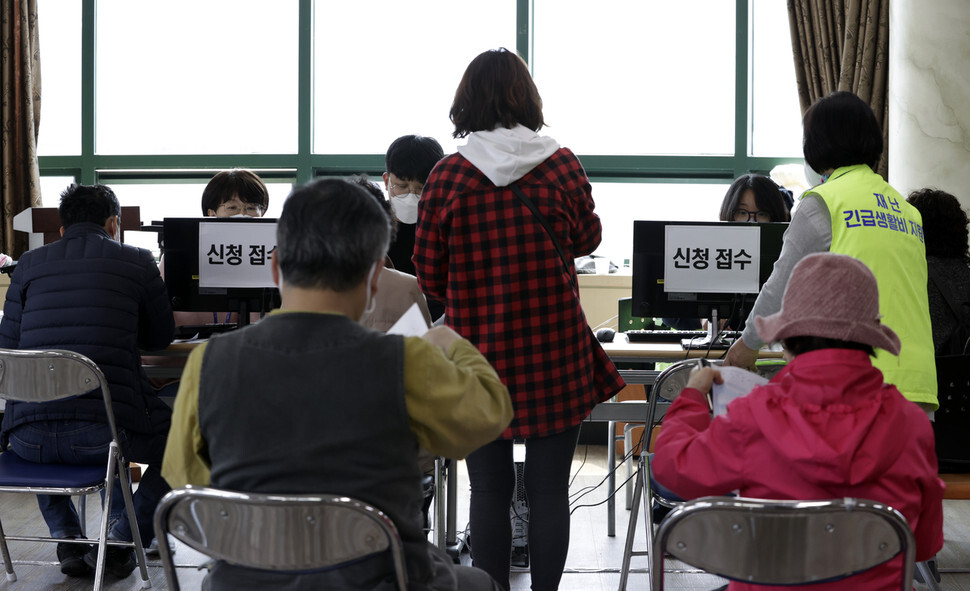

On the morning of Apr. 16, the Hwagok 1 community center in Seoul’s Gangseo District was thronged with senior citizens. They were there to request basic disaster allowance benefits from the city. A center employee told them there was no need to rush, but the elderly visitors pushed ahead, concerned that being too late would result in no benefits. A message on the ground calling for “social distancing” was ignored. A flustered center employee explained, “We start taking applications at 9 am, and they began lining up about 30 minutes ahead of time.”

Amid the novel coronavirus outbreak, the city of Seoul had been accepting applications by mobile phone and online since Mar. 30 for basic disaster allowances of 300,000-500,000 won (US$246-410) per household to those earning less than the median income (4.75 million won, or US$3,896, for a family of four). But with Apr. 16 marking the first day of on-site applications, seniors who had been having difficulties with mobile and online applications began flocking to local community centers.

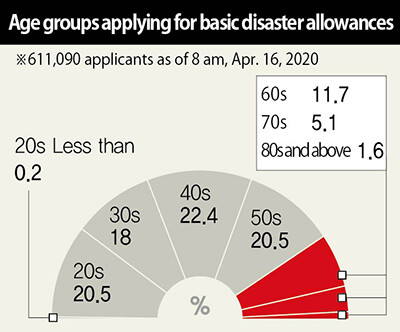

Among the 611,090 people who had previously requested basic disaster allowances as of 8 am that day ahead of the on-site applications, similar rates of around 20% were found among those in their 20s to 50s -- but for those in their 60s and 70s, the respective rates were just 11.7% and 5.1%. The number provided an indicator of how much senior citizens have become excluded from digitally based information. Indeed, when the Hankyoreh paid visits on Apr. 16-17 to centers in Seoul neighborhoods with large populations of residents aged 65 and over -- including Yeokchon in Eunpyeong District (7,969), Hwagok 1 in Gangseo District (7,812), and Oryu 2 in Guro District (7,618) -- most of the on-site applicants were senior citizens.

“I came after hearing about it from other seniors I know,” said Kim Geon-rye, an 81-year-old visitor at one of the neighborhood centers. “I don’t really know about text messaging.”

According to figures from the city of Seoul, a total of 59,035 people submitted allowance applications through visits to neighborhood centers alone on Apr. 16.

“People in their 60s and over were estimated to account for over 70% of those applying on site between Apr. 16 and 17,” said an official with one Seoul district.

The senior citizens applying for emergency disaster allowance benefits were mostly those with small and irregular earnings and those dependent on a basic pension. One 73-year-old woman who spoke with the Hankyoreh in front of the Yeokchon 1 residents’ center had had to quit her difficult job as a taxi driver late last month after five years. As the virus spread, her passenger numbers fell too low for her to cover her company payments.

“Since February, it had become common for me to go around for two hours without a single fare,” she explained. She has a son in his 40s, but as a freelancer, he too has been pulling in almost no earnings since the outbreak began. The woman explained that covering living costs is a secondary concern, with her biggest worry having to do with replaying the family’s tens of millions of won in debt. Even the 300,000 won (US$246) in basic disaster allowance benefits for a two-person household is restricted to use at businesses such as restaurants and supermarkets.

“I don’t understand why there are so many restrictions on where you can use it when it isn’t even that much money,” she said. “There are a lot of people who have urgent debts to repay.”

In front of the Oryu 2 community center, a 68-year-old privately owned taxi driver surnamed Kim sighed, “On an average day, I’d been making around 200,000 to 300,000 won [US$164-256], but since March I’ve had a lot of days where I didn’t even make 40,000 won [US$33].”

“I’m not planning on operating for now because I’m losing money,” Kim said.

A 58-year-old surnamed Park who drives a truck and sells fruit near the Yeokchon 1 neighborhood said sales had fallen by more than half since the outbreak.

“A lot of people are complaining about how small the disaster allowance is, but for people in the working class, every penny is welcome,” Park said.

An 81-year-old surnamed Lee who reported a basic pension of 300,000 won (US$246) as his only income said, “I’m not making anything, and I have to spend money on face masks because of the coronavirus. I want to get the allowance as soon as possible.”

Only households earning less than median income eligible for benefitsMany residents ended up wasting their efforts, either because they did not know the terms for applying for the allowance or because they were unaware of the weekday-based system for applications. Only those who belong to a household earning less than the median income and not receiving any other forms of support such as a youth allowance from the central government or the city of Seoul can apply for emergency allowance benefits; as in the case of publicly supplied masks, applications are only accepted on a specific day of the week based on the last digit of the applicant’s birth year. Lee Gyeong-jae, a 70-year-old resident who visited the Hwagok 1 residents’ center on Apr. 16, explained, “I was born in 1950, and I didn’t know they were only taking applications [today] from people whose resident registration number ends in four or nine.”

A 70-year-old surnamed Choi said, “I asked one of the staff, and they said you can’t [apply] if your income is more than 1.7 million won [US$1,394] before taxes.”

“I’m a security worker, and I couldn’t get [benefits] because I’m earning the minimum wage [1,795,310 won per month as of this year],” Choi sighed before turning back around.

By Chai Yoon-tae and Park Yoon-kyung, staff reporters

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0512/3017154788490114.jpg) [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks![[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’ [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/5217153290112576.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’- [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- 2Seoul’s plan to adopt SM-3 missiles is like wanting a sledgehammer to catch a fly

- 3Yoon rejects calls for special counsel probes into Marine’s death, first lady in long-awaited presse

- 446% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 5S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 6Behind-the-times gender change regulations leave trans Koreans in the lurch

- 7Japan says its directives were aimed at increasing Line’s security, not pushing Naver buyout

- 8Yoon voices ‘trust’ in Japanese counterpart, says alliance with US won’t change

- 9US expert says THAAD can’t distinguish between real and decoy warheads

- 10Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February