hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Recalling seeing soldiers secretly burying bodies behind Gwangju Prison

“I witnessed soldiers burying the bodies of civilians behind the general affairs department at Gwangju Prison.”

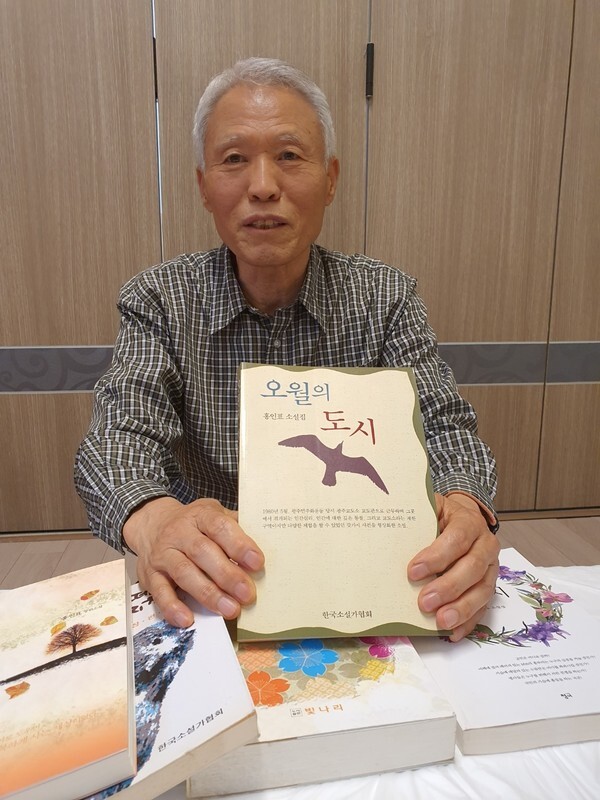

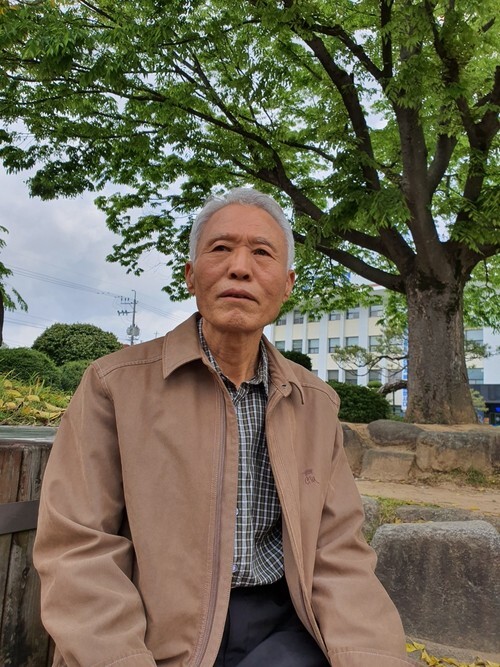

When 74-year-old writer Hong In-pyo spoke with the Hankyoreh in Jangheung, South Jeolla Province, on May 1, he clearly remembered an incident connected with allegations of secret burials at the old Gwangju Prison, in the Gakwha neighborhood of Gwangju’s Buk (North) District.

Hong was on the 4th watch tower, around dusk on May 21, when he saw something he’d never forget: soldiers from the 3rd Airborne Brigade were secretly burying the body of a civilian. Two other bodies were buried inside the barbed wire of the prison compound. “They pulled out 70 or 80 people from two canvas-covered trucks like they were luggage, beat them, and made them put their heads on the ground with their buttocks in the air,” Hong said, describing an uncomfortable and humiliating position commonly used as corporal punishment in Korea.

When the 3rd Airborne Brigade relocated to Gwangju Prison on May 21, it brought along demonstrators that were in detention at its quarters at Chonnam University. The three demonstrators buried on the prison grounds likely suffocated to death while being taken to the prison.

“After a couple of days, I saw three or four bodies being flown out by helicopter,” Hong said. Because of the events unfolding in Gwangju, Hong had to stay at the prison for 10 days, unable to go home even when his shift was over. Hong recounts his experience at the prison during the uprising in meticulous detail in his short story, “The City in May.”

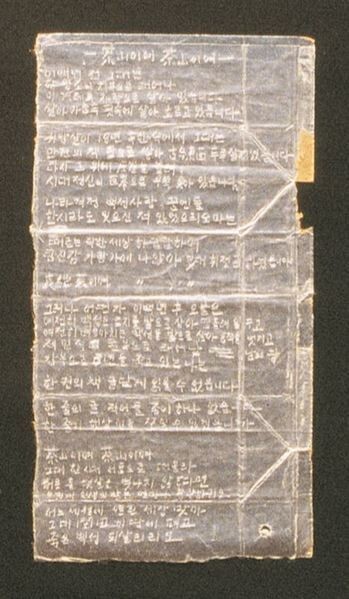

Hong became a corrections officer in 1977. While serving at Gwangju Prison, he got to know several prominent activists. Park Seok-mu (a future lawmaker who was jailed under the Park Chung-hee administration) came by in 1980 and asked Hong to look after Kim Nam-ju (1946-1994), a poet who’d been relocated to Gwangju Prison. “Kim Nam-ju said he wanted a way to write poems. I told him that milk came in tinfoil that he could write on with a sharp object. He asked me for a nail, so I smuggled him one from the carpenter’s shop,” Hong said.

Hong hid Kim’s poems by wrapping them in plastic film and burying them in his yard. Of the 510 poems that survive Kim, 360 were written from behind bars.

After the two became friends, Hong shared his desire to write fiction. So Kim introduced Hong to Lim Heon-yeong, a critic who was also incarcerated there. Hong was soon reading fiction and writing prose; he ultimately debuted with a novel called “King of the White House,” which was published by Changbi in 1989.

“My novel deals with the secret dealings that go on inside prisons. After it came out, I was called in by the prosecutors, who told me to stop writing. But I shot back that I was going to keep writing fiction,” Hong said.

Hong quit his position at the prison in 1992, after 15 years on the job, and turned to manual day labor and security work at apartment complexes and universities. He’s never stopped writing fiction, though. He released a short story collection called “Ring of Flowers” last year and won a prize from the Korean Literary Critics Association in 2014.

By Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 3Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 4[Cine feature] A new shift in the Korean film investment and distribution market

- 5[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 8[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 9[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 10Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan