hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Still trying to find a comrade, 40 years later

Forty years have passed since the Gwangju Democratization Movement, which began on May 18, 1980, but we have yet to learn the full truth about the movement, including the number of those killed, the whereabouts of the missing, and the identify of those who ordered government troops to open fire on protesters. We’ll be exploring the need for a thorough investigation based on the testimony of the survivors and the family members of the victims, as well as the challenges that remain, over the course of three articles.

A second’s hesitation was the crossroads between life and death. When an airborne soldier with murder in his eyes shouted for members of the Gwangju citizens’ militia to come out, 17-year-old Choe Jin-su hesitated for a moment, giving a comrade surnamed Kim time to step forward. A soldier with a staff sergeant’s insignia approached and shot Kim in the right temple with an M16 rifle and then aimed the barrel at Choe. But a captain ordered the staff sergeant to take Choe outside, explaining that killing him in the house would create too much noise. Instead of shooting Choe, however, the soldiers took him and three other members of the civilian militia to the airborne company headquarters, enabling Choe to evade death.

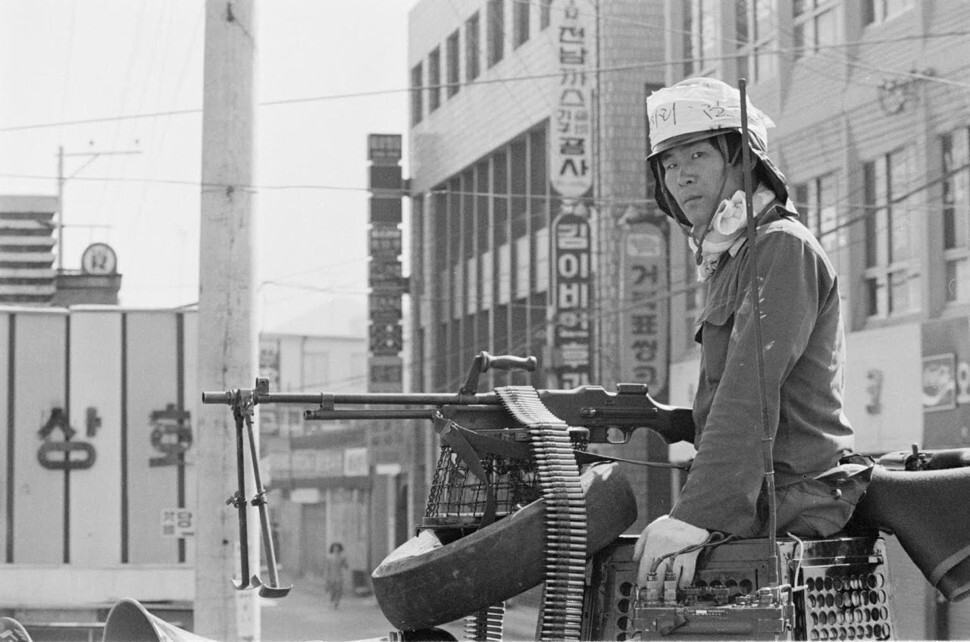

Choe sat down with the Hankyoreh in Ansan, Gyeonggi Province. “Eleven of my comrades and I were riding in a truck toward the Songam neighborhood on the orders of the militia leadership on May 24 when we encountered an armored car from the 11th Airborne Brigade. The car sprayed us with a .50 caliber machine gun, so we scattered and took cover in the houses in the area,” he recalled.

“We laid low in a house for about 40 minutes amid the ferocious roar of guns and rifles until an order was given to stop firing and the sound died down. Curious about what was happening, we poked our heads out of the window and saw 40 or so soldiers surrounding the house.”

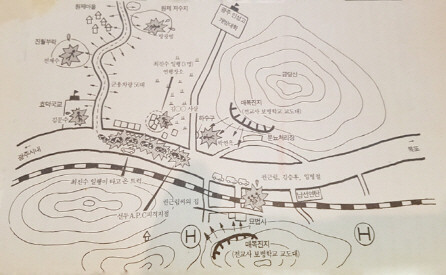

The gunfire that Choe had heard while hiding in the house turned out to be a skirmish between the 63rd Battalion of the 11th Airborne Brigade, which was withdrawing to the Gwangju Airfield, and a unit of drill sergeants of the Republic of Korea Army Infantry School, which had mistaken the airborne troops for members of the civilian militia. Nine soldiers were killed and 33 wounded in this friendly fire incident in the Songam neighborhood. Angered by the casualties, the government troops lashed out at innocent civilians, and the militia member named Kim was killed in the process.

Choe was carted off to a holding cell at the Army Training and Doctrine Command at Sangmudae base. On July 1, 1980, investigators brought him back to the Songam neighborhood where the incident had occurred. When Choe asked the residents about what had happened to Kim’s body, they said soldiers had left the body behind, so they’d given it a temporary burial on a hill nearby called Geumdang. The residents said the soldiers had returned to collect the body on May 31 and didn’t know what had happened to it afterward.

Choe, who was released from jail in October, felt that Kim had died in his stead. Choe didn’t know the young man’s first name or age, but he wanted to hold a memorial ceremony for him. Choe showed up at the Gwangju hearings at the National Assembly in 1989 and the Ministry of National Defense’s fact-finding committee in 2006 to ask them to look into what happened to Kim’s body. He even offered a 5 million won (US$4,065) reward, but without any results. Choe took part in the documentary film “Kim-Gun (Mr. Kim),” which was released last year, and is working to erect a statue in his honor, all as part of his efforts to find the young man’s body.

“After the Gwangju Democratization Movement, I looked high and low for the other comrades who’d been with Kim and me, but all of them had vanished. The soldiers stationed in the city can’t be any older than their mid-60s. I really hope we’ll learn the truth,” Choe said.

Witness testifies to 52 burials

Kang Gil-jo (38 years old at the time) was protesting when he was arrested in front of Chonnam National University on May 20 by soldiers from the 3rd Airborne Brigade. Kang demands the search for 52 people who were killed in the old Gwangju Prison. “Eleven people were smothered to death while the 3rd Airborne Brigade was withdrawing from the prison. The soldiers placed numbered strips of wood on the corpses and took photographs of them,” Kang said.

Kang was locked up in a factory that produced straw bags in the prison with about a hundred other demonstrators. People were killed there every day until he was taken to a jail at Sangmudae on May 31, their bodies carried off by army helicopters in the early morning hours. Kang kept a tally of the corpses on a scrap of paper; there were 52 altogether, including the 11 who died in transit.

“There were probably more victims, since they must have buried the people they shot outside the prison. I’m 80 years old, but I’d really like to see the truth of Gwangju brought to light before I die,” Kang said.

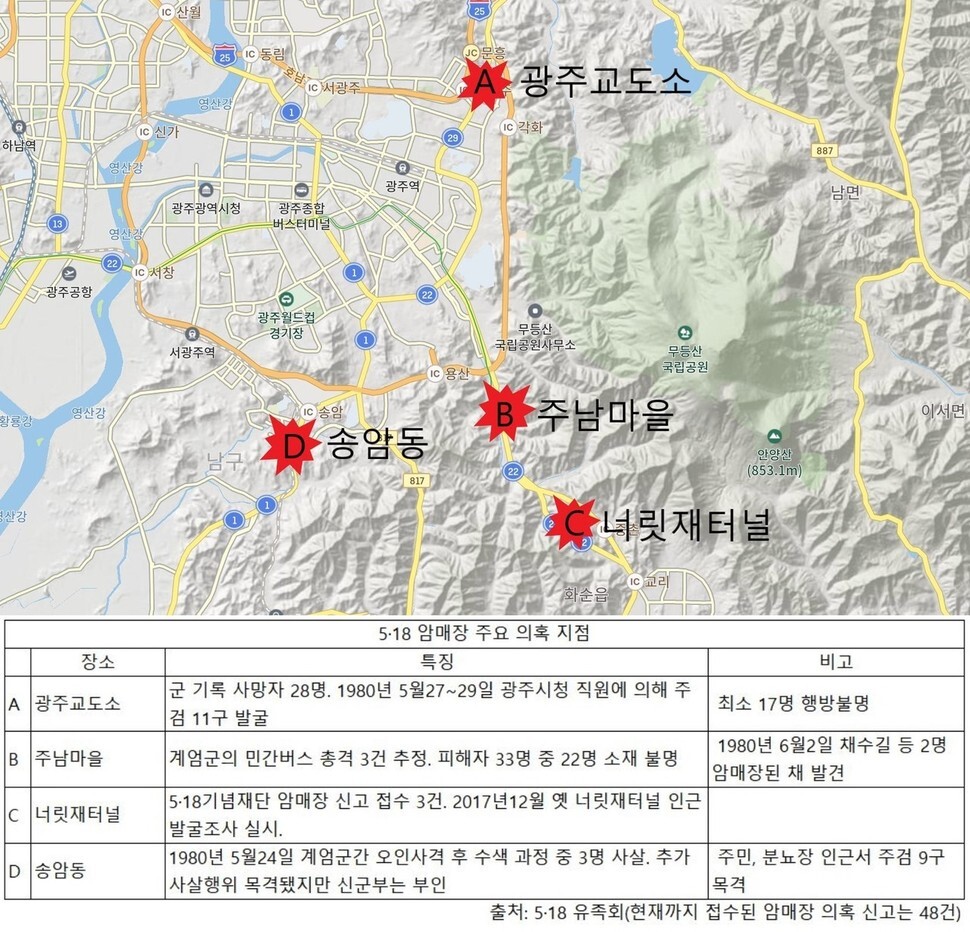

Determining the whereabouts of the missing is one of two unfinished tasks, the other being figuring out who ordered the soldiers to open fire on the demonstrators. There are currently 78 people on Gwangju’s official list of the missing and 242 other missing claims that the city doesn’t recognize.

The issue of the missing bodies is linked to accusations about secret burials. A sergeant surnamed Kim with the 62nd Battalion of the 11th Airborne Brigade testified to the Defense Ministry’s fact-finding committee in 2007 that certain soldiers wearing infantry uniforms had apparently gone into Gwangju and dug up temporary burial sites on the orders of the commander of the 62nd Battalion. Kim’s testimony backs up allegations that the airborne troops secretly recovered bodies from shallow graves.

The city of Gwangju and the May 18 Memorial Foundation have carried out five searches for temporary gravesites — in 2002-2003, 2006-2007, 2009, 2017, and this year — without yielding any results, and former President Chun Doo-hwan and other members of the military junta that ruled Korea at the time continue to deny allegations about the secret burials.

“We will confirm the number and location of those who went missing and determine the truth of allegations about secret burials and abandonment of corpses,” a government commission investigating the Gwangju movement said in a statement on May 12. It remains to be seen whether that promise will be kept.

By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 3Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 4Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 5Anti-immigration candidate marauds across Korea with squad detaining foreigners

- 6Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 7Alleged drug use by Korean A-listers rocks nation – but not for the first time

- 8[Column] Unsettling moves by the UN Command lay way for Korean involvement in Taiwan

- 9[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 10Bills for Itaewon crush inquiry, special counsel probe into Marine’s death pass National Assembly