hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

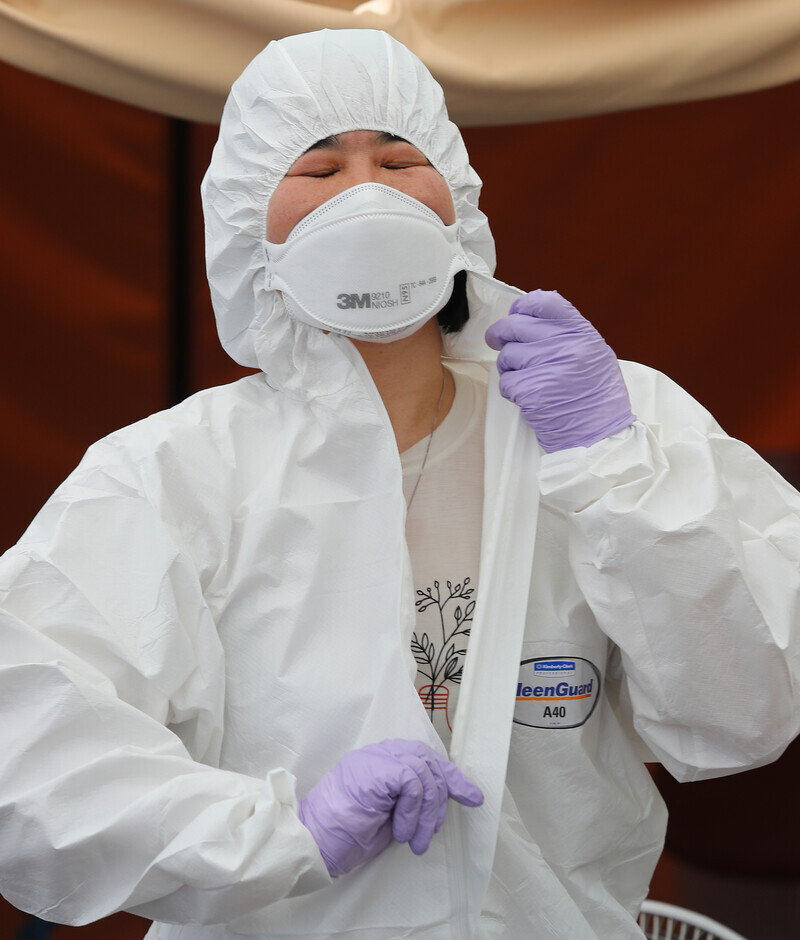

Public health workers overworked and underpaid in struggle to fight COVID-19

“There have been a few times when I experienced mortal fear -- the feeling that if I kept going, I was going to end up dead. I wanted to run away, but I couldn’t just leave the patients behind. [. . .]”

Kim Ye-jin (pseudonym) made the decision to leave her job as a physician at a public health center in the Seoul Capital Area (SCA) amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Even when she slept, her energy never seemed to recover. She began crying at odd moments. Her body and mind were both exhausted. Since mid-February, she had not had a single day of rest. Whenever a patient was diagnosed in her area, she would be testing patients from 8 am to 10 pm. She was also on standby at the center on weekends for emergencies, including testing for overseas arrivals.

“I was there in Level D protective gear, seeing hundreds of patients lined up in front of the screening clinic tent like a coiled snake, and I couldn’t breathe,” she recalled.

There was one day where 350 people came to the clinic. The center had five doctors working; as the newest among them, Kim was tasked with one of the two screening clinic tents. “I asked them repeatedly to provide more doctors, but with the COVID-19 crisis it was tough to find doctors to work for 14,000 won [US$11.53] in overtime pay,” she explained. As it is, public health center physicians earn less than two-thirds what regular physicians make. In early April, Kim was hospitalized for work-related exhaustion and diagnosed with depression.

It is ordinary doctors like Kim and public health doctors (doctors serving to fulfill their mandatory military service requirement) who work at city, county, and district public health centers. Like regional medical centers and national university hospitals, the public health centers are classified as “public health and medical institutions” according to the Public Health and Medical Services Act. As of June 2019, a total of 788 physicians were working at 256 public health centers nationwide -- around one for every 65,800 people.

Four months have passed since the first patient was diagnosed with COVID-19 in South Korea. At the public health and medical institutions on the front lines in treating patients, many medical professionals have succumbed to burnout like Kim. According to the findings of an “initial survey of Gyeonggi Province coronavirus medical and disease prevention response team perceptions” published on June 11 by the Gyeonggi Province public health and medical service support team and a research team led by Seoul National University Graduate School of Public Health professor You Myoung-soon, 62.9% of the 1,112 medical professionals and local response team members who had been treating coronavirus patients responded that they felt “emotionally exhausted as a result of coronavirus-related duties.” When asked about their level of “trauma stress” in connection with the coronavirus response, 16.3% said they required “immediate [psychological] assistance.” At 43.6%, the highest rate of response among institutions was found among medical staff at public hospitals like Gyeonggi Provincial Medical Center and Seongnam Citizens Medical Center.

Public health doctors comprise only 10.9% of those in private hospitalsBetween June 4 and 15, the Hankyoreh interviewed seven doctors and nurses who had cared for COVID-19 patients at public health and medical service institutions. They reported the biggest obstacle to the coronavirus response as being a “shortage of staff.” Legally, public health and medical service institutions are required to provide the first public health and medical services in disasters such as infectious disease outbreaks. But of the 149,344 doctors employed in South Korea as of late 2018, just 16,231 were working at public health and medical service institutions. The number of public health service professionals amounts to just 10.9% of the number of doctors in privately run hospitals. The ratio of public health physicians to privately employed ones has been on the decline, slipping from 11.2% in 2016 to 11% in 2017 and 10.9% in 2018.

Nurses, who have a large amount of face-to-face contact with coronavirus patients when taking blood samples, administering medications, changing diapers, and performing other duties, have also been suffering from acute physical and psychological stress. Yang Min-a (not her real name), a nurse who has been working for over 20 years at Gyeonggi Provincial Medical Center Ansung Hospital, said she has experienced “growing anxiety” amid the recent increase in the number of coronavirus patients in the SCA. Many nurses have quit because of the strenuous labor associated with caring for covid-19 patients; the number of nurses per shift has dwindled from 10 to six or seven. The hospital currently has around 60 COVID-19 patients hospitalized, meaning that each nurse is looking after around 10 patients. The night shift, which reports for duties at 11 pm, has dropped by half from eight to four.

“We’ve been working without any days off due to the increasing patient numbers. The leave that the Gyeonggi governor talked about giving us is a pipe dream,” Yang said.

“Compared with university hospitals and other private hospitals, the regional medical centers are public hospitals without any additional staff beyond the nurses, who have to do everything from cleaning the wards and transporting patients to hammering shut the plastic medical waste containers,” she explained.

Medical professionals in the Daegu/North Gyeongsang area, who faced new patient numbers as high as 741 per day in late February, experienced burnout early on. Lee Mi-hwa (pseudonym), who has worked at Daegu Medical Center for 20 years since 2001, found herself regretting being a nurse for the first time in her life during the COVID-19 outbreak. On Feb. 21 when the first patients started arriving, she had to work for 11 hours dressed in protective gear before she was able to go home with her now-cold lunchbox meal. Over the next 10 days, her working hours were adjusted into two shifts of 12 hours starting at 8:30 am. At one point amid the explosion in cases related to the Shincheonji Church, she had to look after 20 patients on her own. Even with 200 nurses employed, the number was far too small to deal with over 350 patients, given the shift system.

Workers get no public appreciationLee first began experiencing periodic urges to quit around mid-March, after the hospitalization of patients from Saeronan Oriental Medicine Hospital and Hansarang Convalescent Hospital. The nurses were tasked with everything from changing diapers to wiping feces from patients suffering from dementia and tending to bedsores. Diaper changing for a single patient with dementia and severe COVID-19 systems was at least a four-person job, with one nurse needed to arrange the respirator and other lines going into the patient’s body, another to hold the patient to one side, and others to change the diaper. Nurses also had to deal with complaints, including people asking “Why am I being kept here when I feel fine?” or “Are you going to take responsibility if I die?”

“Public hospitals have to take every patient, no matter what, and as the situation dragged on, the nurses’ immune systems were stressed and we became exhausted,” Lee recalled. “I lost all my drive when the city of Daegu started talking about the ‘nurse’s responsibility’ when a nurse colleague tested positive.”

“Rather than having ‘thank you challenges’ to support medical staff, they needed to be providing more nursing staff with additional pay to prepare for a second outbreak,” she urged.

Private hospitals can’t be relied on in disaster situations due to profitabilityJeong Hyeong-joon, policy committee chair for the Korean Federation of Medical Activist Groups for Health Rights, said, “Severe cases are evenly distributed across regions at the moment, but the private hospitals are short of the necessary trauma and disaster medical staff due to profitability issues.”

“Public health services are a public asset like firefighters and police officers, and we need to establish a public health university to train the necessary physicians, nurses, and other public health medical professionals to respond to things like infections and trauma,” he added.

By Kwon Ji-dam, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence![[Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/4417158464854198.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

[Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

Most viewed articles

- 1China calls US tariffs ‘madness,’ warns of full-on trade conflict

- 2[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 3[Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- 4[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

- 5[Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- 6US has always pulled troops from Korea unilaterally — is Yoon prepared for it to happen again?

- 7[Book review] Who said Asians can’t make some good trouble?

- 8Naver’s union calls for action from government over possible Japanese buyout of Line

- 9Could Korea’s Naver lose control of Line to Japan?

- 10[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line