hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

S. Korean professor doxed by digital vigilante group for a crime he didn’t commit

The phone number and other personal information of a university professor who had allegedly attempted to purchase illicit pornographic material (which was shared among users in a Telegram chat room in an infamous case known as the Nth Room incident) was uploaded to a South Korean website called Digital Prison, a website that doxes alleged sex offenders out of frustration for the judicial system’s lenient approach to sex crimes.

By the time his innocence was proven, damage was already doneBut when the police launched an investigation, the allegations turned out to be untrue. By that point, the professor had already suffered terribly because of the disclosure of his personal information. This incident, along with an earlier suicide by a university student who was doxed by Digital Prison, raises questions about how South Korean society should regard vigilante justice that dispenses with ordinary judicial procedures.

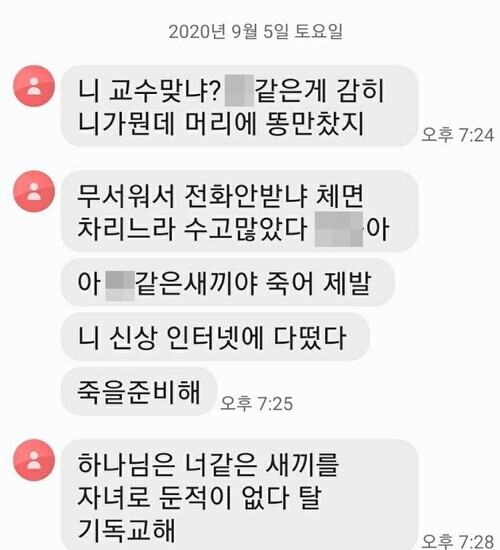

“Get ready to die.” “Can you please just die?” Each day, Chae Jeong-ho, 59, a professor in the mental health department of the medical school at the Catholic University of Korea, receives dozens of text messages like these, full of curses and vulgarity.

But Chae used to receive even more. When his personal information — including his mobile phone number, photograph, and workplace — were posted on Digital Prison at the end of June, he was getting hundreds of obscene text messages and threatening phone calls each day. A petition was even posted on the Blue House website asking for him to be prosecuted. Chae objected that the allegations were groundless, but Digital Prison administrators countered by posting screenshots of text messages.

Members of his academic society called him an “unethical doctor,” referred him to the ethics committee, and even asked for his lectures to be suspended. “This obviously has caused pain for my family members. But on top of that, I’ve even heard from former patients who say they can’t trust me anymore. I’m suffering from frustration and depression,” he told the Hankyoreh over the phone on Sept. 7.

The tables were turned when the police released the results of their investigation at the end of August. The Daegu Metropolitan Police Agency had taken up the case after Chae sued Digital Prison for defamation. After analyzing 100,000 messages on his mobile phone, 50,000 records on his browser, and 87,000 multimedia items he had viewed, police officers concluded that Chae wasn’t the person who had exchanged text messages with Digital Prison.

“Chae’s phone does not contain any text messages corresponding to the screenshots posted on Digital Prison, even including deleted data on his phone. No videos, images or messages were found that would suggest that Chae attempted to purchase illicit pornographic material or deliberately deleted it,” the police said in an official message sent to the Korean Neuropsychiatric Association, the academic society of which Chae is a member.

According to the statement by the police, the person who sent messages to Digital Prison may have been impersonating Chae, or the messages themselves may have been digitally manipulated. The police explained that the linguistic patterns found in the 99,962 messages on Chae’s phone are completely different from the tone of the messages posted by Digital Prison; the police also said that Chae wasn’t even logged onto the Telegram app when the messages were sent.

“If someone had beaten me up, they would have been arrested and booked for assault, but I haven’t even had the consolation of knowing who caused my pain. Now that the investigation has concluded, I feel like the worst of the pain has passed,” Chae said.

The dubiousness of vigilante justice and how it can target innocent individualsDigital Prison was launched with the goal of directly publishing the personal information of sex offenders as a form of vigilante justice, motivated by frustration about the South Korean judicial system’s tepid approach to prosecuting sex crimes. But recently, the website has been creating victims of its own.

“As a trauma researcher, I’m aware of how much trauma is endured by the victims of sexual violence, and I think sex offenders should be severely punished, too. But no matter how just a cause may seem to be, it can’t be more precious than life itself. Doxing people for unconfirmed crimes is a criminal act,” Chae said.

The police are currently carrying out an investigation of Digital Prison that combines several lawsuits and criminal complaints filed against the website. “The server is based overseas, and the website is presumably operated by several people,” the Daegu Metropolitan Police Agency said.

The administrators of Digital Prison didn’t respond to a request for comment.

By Jeon Gwang-joon, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 5[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 6[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 7[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 8[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 9Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 10[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel