hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

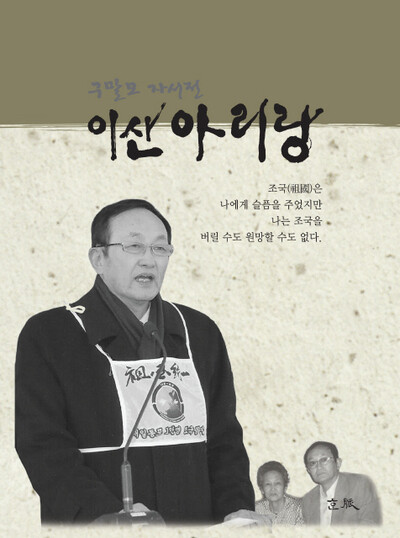

After 40 years, accused spy tells his tragic story

By Han Seung-dong, senior staff writer

“My country caused me pain, but I can neither abandon nor resent it. [. . .] At first, I wasn’t planning to write a book, but my daughter, who grew up as a third-generation Japanese-Korean, my wife, and my friends all urged me to write it, so I did. They said that the only way for people to know that I had finally cleared my name after 40 years of being unfairly regarded as a spy was to publish a book. [. . .] I hope that the book will be a reference for resolving conflict between Korea and Japan, to serve as a guideline for allowing families divided by the Korean War to meet each other freely and for unifying North and South Korea. I also hope that it will be used to teach future generations why an innocent man became a scapegoat of history and had to suffer such a tragedy.”

Japanese-Korean Gu Mal-mo, 78, was the sixth of eight children born to a couple from Yeosu, South Jeolla Province, who were forcibly drafted to work in mines during the Japanese occupation of Korea. Gu grew up in Moriyama in Saga Prefecture, near Kyoto, and completed a master’s degree at Waseda University. After working at the South Korean Embassy in Japan, he came to Korea for a doctorate. This is when he was framed as a spy.

Gu was released in 1981 after 10 years in prison. It was not until Nov. 2012 that his record was finally cleared - 40 years later - by the South Korean Supreme Court. Gu tells his tragic story in the book “A Divided Family’s Arirang”, which was published by Hanmaek.

In a phone interview with the Hankyoreh on Dec. 10, Gu explained that another reason that he wrote the book was because he dreams of the day when Japanese-Koreans, who have become people stuck on the borders, will be able to freely visit North and South Korea regardless of national borders and ideology. He also said that the book represents a heartfelt apology to the spirit of his older brother who took care of him in prison but passed away before he could hear the not guilty verdict and to his unlucky nephews and nieces, who were unable to get jobs or even to leave the country because of the “guilt by association” system in Korea.

Gu came to Korea in 1967 to learn the Korean language and Korean history. He enrolled in the department of politics and diplomacy at Yonsei University and completed his doctoral coursework in two years. After that, while he was preparing to study in Canada, he was arrested on charges of violating the National Security Law and was sentenced to fifteen years in prison.

“My second older sister, who is seven years older than me, had gone to North Korea along with a lot of other Korean-Japanese around 1960 after getting married,” Gu recalls. “In 1970, I went to Pyongyang to meet my sister, who was living in Hamhung.”

Gu had only gone to Pyongyang one time, but the South Korean security authorities claimed he had made two trips to the North to receive orders. He was assigned to go to South Korea, authorities said, to report on the domestic political situation and trends in universities. Gu was rounded up along with eleven other people believed to be part of the same spy network.

Gu was subjected to various kinds of torture by KCIA agents. As a result, he suffered from memory and speech loss for some time and was confined to an intensive care unit. He was beaten so severely that even his family members were unable to recognize him when they came to visit.

However, Gu did not believe it was anyone’s fault that he had been a Japanese-Korean or that he had been locked up in prison. Gu was determined not to die a wretched death inside a shabby prison. He reminded himself that if he did not look forward to the day when Korea and Japan could grow together, and to the day when North and South Korea would be reunified, then all of this would be all his own fault.

After being released from prison, Gu served as the president of the Peace and Unification Alliance in Japan and the chair of the Committee for Peace and Unification of Korean Residents in Japan (Mindan), leading a movement to unify the Korean people.

“Money can’t fix what happened, but for practical reasons, I have filed a few criminal and civil compensation lawsuits. I hope the courts will be considerate enough to bring these to a quick conclusion,” Gu said.

There are about 120 Japanese-Koreans who were convicted of being spies under circumstances similar to Gu’s. Forty of them have requested a retrial, and twenty have been found not guilty and have sued the South Korean government for damages.

“I have not been able to contact my sister in Hamhung for the past two years, and I stopped getting letters from her one year ago. In her last letter, she said that she was lying in a hospital bed . . .”

On the afternoon of Dec. 12, a commemorative event will be held for the publication of “A Divided Family’s Arirang” on the second floor of the convention hall at the new K-Turtle building in Seoul’s Shinchon neighborhood.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 6Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 7[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 8The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 9Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South

- 10Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76