hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

With payday looming, wage hike issue hanging like a dark cloud over Kaesong Complex

Storm clouds are once again gathering over the Kaesong Industrial Complex.

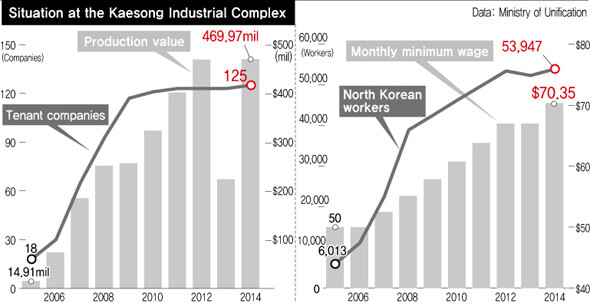

April 10 marks the beginning of March wage payment for North Korean workers at the complex, for whom Pyongyang has unilaterally demanded a wage hike. On Mar. 11, North Korean authorities single-handedly amended 13 provisions in the complex’s labor regulations. Two of those provisions were applied in late February, when Pyongyang announced that the monthly minimum wage would be raised 5.18% to US$74 as of March. It also said it would be raising social insurance payments (similar to the four major types of insurance in South Korea) to 15% of basic wages plus overtime, rather than the 15% of basic wages that it was before. The result was an increase of 5.5%, or US$8.60.

South Korean authorities are keeping a tight rein on the complex’s tenant companies and demanding that they not comply with the demands. On Apr. 2, the South Korean government sent a notice to the tenant companies ordering them not to comply with North Korea‘s unilateral minimum wage hike and insisting that they pay only the agreed-upon wages and social insurance. It also warned that those who did comply with Pyongyang’s terms may not be granted approval to visit North Korea, or could suffer consequences ranging from financial support restrictions to the revoking of business licenses.

The current cap on minimum wage increases at the complex is five percent. The rate demanded by North Korea comes out to just 0.18 percentage points more. But from Seoul’s perspective, the key question is how much more Pyongyang may ask for later.

“If we accept the labor regulations that the North changed without reaching an agreement, we’re giving them a pretext to change other insurance and taxation regulations in the future, and just generally run the Kaesong Industrial Complex however they see fit,” explained a Unification Ministry official.

Pyongyang, for its part, insists it is not backing down. In late March, its Central Special Development Guidance Bureau delivered new guidelines to the North Korean accounting staff at the complex’s businesses ordering them to calculate wages based on the new policy.

Now caught in the middle, the companies have been expressing concerns about the future.

"There hasn’t been any change among the North Korean workers, but we’re worried about how the situation could change going forward,” said the head of one tenant company.

Kim Seo-jin, managing director for the Corporate Association of Gaeseong Industrial Complex (CAGIC), said the situation “becomes much more urgent for the smaller-scale companies and ones with imminent delivery deadlines if they don’t comply with the wage hike and the North Korean workers refuse to do overtime.”

The current wage conflict brings back memories of the five-month shutdown that occurred in 2013. That year, North Korea pulled out its workers over joint South Korea-US military exercises, and South Korea ordered its businesses home. Companies would later report massive losses from the shutdown, totaling some 1.056 trillion won (US$965.1 million). In August 2013, Seoul and Pyongyang held seven rounds of working-level talks before finally drafting an agreement for the complex‘s “internationalization” and measures to prevent future shut downs, and the South-North Joint Committee for Gaeseong Industrial Complex was created to implement its terms.

But the recent unilateral labor regulation change by Pyongyang violates the agreement, which requires the two sides to resolve issues in the Joint Committee. For this reason, there are worries that North Korea may have reverted to its position from before the 2013 shutdown.

Why did Pyongyang go ahead with the unilateral amendment? It could be an effort to make up for the complex to generate the kinds of profits the North had originally planned for.

“It looks as though the North conducted a general analysis of the Kaesong Complex’s projects and found that it wasn’t generating the anticipated profits, and now it’s trying to make up for that,” said Cho Bong-hyun, a senior researcher at the IBK Economic Research Institute.

Others factors could be the recent launches of balloons containing propaganda leaflets by South Korean groups and joint military exercises with the US. The changes may also be the start of a push by North Korea to turn the complex into a Pyongyang-led operation rather than a matter of inter-Korean agreement.

“What we’re seeing here is another eruption of the same issues that have piled up over the past eight years since South Korean public servants were pulled out of the Kaesong Complex under the Lee Myung-bak administration in 2008,” said Kim Yeon-chul, a professor of North Korean studies at Inje University.

“This looks to be an attempt by North Korea to change the complex’s management from a joint effort by South and North to one driven by North Korea,” Kim added.

Meanwhile, the issue of land usage fees, which go into effect this year, presents another potential source of conflict. In 2004, North Korean authorities signed a rental agreement with individual businesses, including South Korea‘s Hyundai-Asan, which would assess the fees once ten years had elapsed in 2015. In Nov. 2014, a North Korean official visited the Joint Committee to propose discussions on the issue. Pyongyang had previously announced immediate plans in 2009 to collect land fees of US$5-10 per 3.3 square meters, but was stymied by South Korean objections. Seoul’s position is that the demand is excessive in light of precedents in other countries such as Vietnam, where international industrial complex land fees come out to US$2.80 for every 3.3 square meters.

The complex’s role for both North and South could be undermined if the conflict isn’t resolved and operations are not normalized.

“Right now, Chinese consignment processing complexes are popping up on the border with North Korea, and there are more than 20,000 workers working in Russia,” said Kim Yeon-chul. “The relative status of the Kaesong Complex in North Korea appears to be waning.”

An extended dispute also appears likely to result in increasing South Korean exhaustion with the complex, which has been the center of numerous inter-Korean conflicts to date.

North Korea could reverse its measures and return to the spirit of inter-Korean consensus, while South Korea works to restore relations by lifting the May 24 Measures imposed in the wake of the 2010 sinking of the ROKS Cheonan warship.

A senior South Korean government official, speaking on condition of anonymity, said North Korea should “abide by the current agreement, and follow that agreement in resolving the wage hike matter and moving forward to the next stage.”

Lim Eul-chul, a professor at the Kyungnam University Institute of Far Eastern Studies, said Seoul “should get inter-Korean dialogue moving again by blocking the propaganda leaflet launches and showing that it is sincerely committed to improving relations with the North.”

Kim Yeon-chul said the most important step by Seoul would be to lift the May 24 Measures.

“There’s no way forward with the Kaesong Complex as long as new investment is barred by the May 24 Measures,” he said.

By Kim Ji-hoon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1‘Right direction’: After judgment day from voters, Yoon shrugs off calls for change

- 2[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- 3[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 4Where Sewol sank 10 years ago, a sea of tears as parents mourn lost children

- 5Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 6[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 7Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range

- 8Umbrella with holes: New NK missiles prove Seoul’s defense system to be faulty at best

- 9Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?

- 10[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test