hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Correspondent’s Column] Author recounts little known story of Japanese comfort women

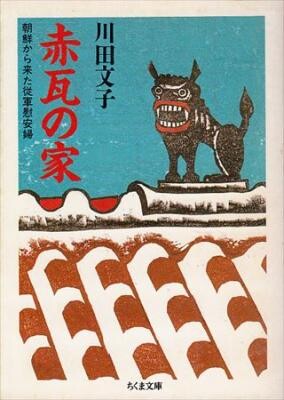

This October, I attended a seminar about Japanese comfort women at the Women‘s Active Museum on War and Peace (WAM), located near Waseda University in Shinjuku, Tokyo. In the seminar, titled “Listening to the Stories of the Japanese Comfort Women,” nonfiction writer Fumiko Kawada related what she had been told by former Japanese comfort women, who are little known even in Japan. Kawada is the author of the nonfiction book “The Red Tile-Roofed House,” which is based on her interview with Bae Bong-gi, the first Korean to go public with her experience as a comfort woman for the Imperial Japanese army.

Kawada told the story of Tamako Ishikawa (a pseudonym), who was born in Yokohama. During World War II, Ishikawa lived at comfort stations in places such as Rabaul, Papau New Guinea. She testified that she sometimes had to service between 100 and 200 men a day. In 1988, an article in the magazine Asahi Journal wrote that Ishikawa was a Korean comfort woman. But the people who knew Ishikawa were doubtful about whether she was Korean, since her lifestyle and language were quite different from those of people born on the Korean Peninsula.

Another source of doubt is that Ishikawa was born in 1908, at a time when an extremely small number of Koreans were in Japan, most of them students. Kawada said that she visited the hospital where Ishikawa was staying in 1991, the year that Ishikawa passed away. Kawada recalled Ishikawa being so sick that she could not bring herself to ask whether Ishikawa was Korean or Japanese as she had wanted. After Kawada’s friends suggested she could get to the bottom of that by asking Ishikawa her real name, Kawada went back to the hospital – but by that time, Ishikawa had already died.

In Kawada’s view, it does not really matter whether Ishikawa was Korean or Japanese. In the end, she said, what matters is that Ishikawa was a victim of human rights abuse. Kawada also told the story of a Japanese woman named Tami (a pseudonym), who had been at a comfort station in Japan. As a young child, Tami had been so diligent at school that her friends said she would go on to study at Ochanomizu University (a university for women). But because of her family’s poverty, she was sold to a brothel and then, during World War II, also spent time at a comfort station. According to Tami, people around the comfort station would thank her for her service to her country.

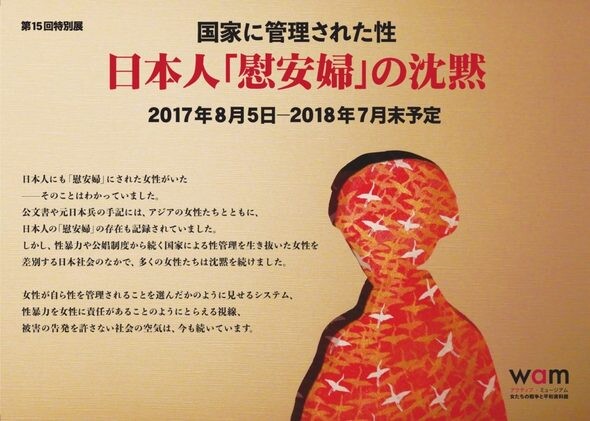

WAM is currently holding an exhibition titled “The Silence of Japanese Comfort Women: State-Managed Sexuality.” This exhibition, which will be held through July of next year, displays the stories of Japanese who have admitted that they were comfort women for the army. The exhibition also explains in detail the context in which the comfort women system developed.

It is widely believed that the Japanese army started organizing the comfort stations around the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. The apparent catalyst was the frequency of sexual assaults by Japanese troops and the reporting of these incidents in the West. The Japanese military authorities set up the comfort stations, ostensibly to prevent soldiers from committing sexual assault, and many women from Korea, China and various countries in Southeast Asia became comfort women. Inside Japan, it was typically women from poor family who ended up in that position.

The exhibition also says that, following Japan’s defeat in World War II, it set up comfort stations for American troops, with the goal of protecting the chastity of the larger female population. The exhibition explains how Japan “managed” women’s sexuality and created a structure in which victims remain silent.

Since South Korea and Japan reached an agreement on the comfort women in 2015, one often hears in Japan that the comfort women issue is viewed not as a human rights issue but as a diplomatic dispute. It was memorable to hear Kawada remark toward the end of the seminar that “this is a human rights issue.”

By Cho Kye-won, Tokyo correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 7[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 10[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father