hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

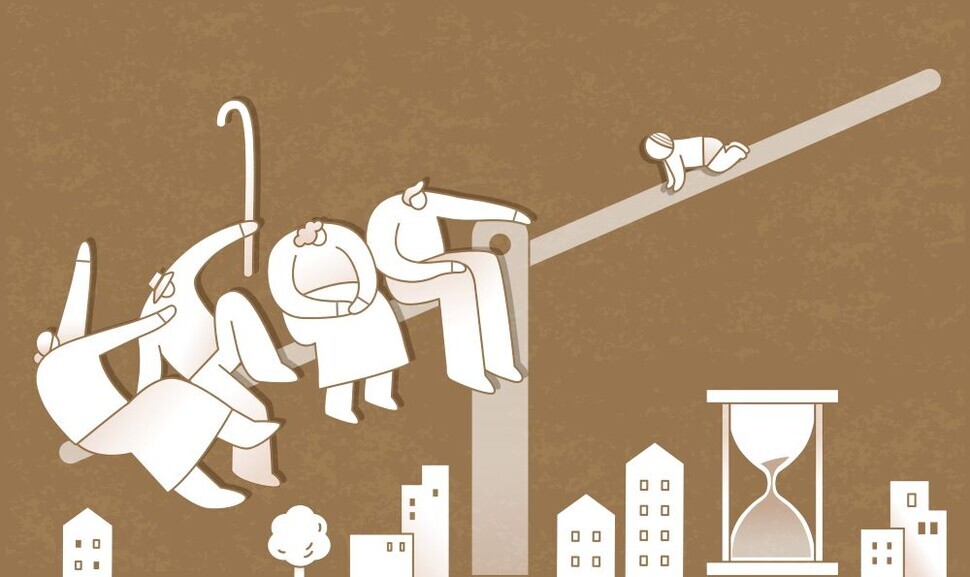

S. Korea to see negative growth by 2050s if record-low birth rates persist, says BOK

If South Korea’s birth rate stays on its current trajectory, the country is likely to see a negative economic growth rate starting in 2050. If the Korean government fails to combat plummeting birth rates, which are falling at an unprecedented pace, the economy will start shrinking. The Bank of Korea has proposed that the government increase its budget for subsidizing living costs, youth employment, and child-rearing expenses.

Released by the central bank on Sunday, a report titled “Measures to Combat the Causes and Effects of Extreme Population Abnormalities Such as a Super-Low Fertility Rate and a Super-Aging Society,” states that South Korea’s total fertility rate fell from 0.81 in 2021 to 0.78 in 2022. According to the report, South Korea had the lowest fertility rate of all OECD countries in 2021, unless Hong Kong is counted as a country.

According to the study, if South Korea maintains its current fertility rate, there is a 98% chance that the country’s population will fall below 40 million by 2070. This finding was based on a scenario in which the government fails to effectively combat plummeting birth rates. The study determined that in such a scenario, there is a 68% chance that the South Korean economic growth rate will fall below 0% in the 2050s. This calculation is based on the trend rate of growth, which excludes short-term economic fluctuations. In short, the size of the country’s economy is bound to shrink if its population does.

Bank of Korea researchers pointed to the pressures of competition that young people face as one of the primary causes of declining fertility rates. In a survey of 2,000 people aged 25 to 39, couples with high levels of perceived competition pressure were found to want to have a significantly lower number of children (0.73) than couples with lower perceived competition pressure hope to have (0.87).

Researchers also pointed to living costs, unstable employment, and child-rearing costs as factors in the low fertility rate. Youth unemployment is high, inequality in the labor market is worsening, real estate prices are soaring alongside the financial cost of raising children. All of these factors contribute to anxiety that prevents couples from having children, the report found.

While a previous survey showed 49.4% of all employed people expressing the intent to marry compared with 38.4% of unemployed people, the proportion of irregular workers hoping to marry (36.6%) was even lower than the rate among unemployed people.

Researchers suggested the total fertility rate could be raised from its current level of under 0.8 to over 1.5 through policies targeting these causes head-on.

Their conclusion is that the solution will necessitate relieving the population concentration in the greater Seoul area — which is exacerbating competition pressures — while taking action to stabilize housing prices and household debt and improve the dual labor market structure. They also advised increasing budget support from the government to alleviate child care concerns.

Indeed, the researchers’ analysis of data for 2019 predicted that if South Korea’s urban population concentration level of 431.9 were to be lowered to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average of 95.3, this would translate into an increase of 0.414 in the total fertility rate.

Other factors that the analysis showed would significantly contribute to raising the rate would be the attainment of OECD average levels in the percentage of children born outside of marriage (0.159), the employment rate for younger people (0.119), actual child care leave usage time (0.096), and family-related government expenditures (0.055).

A decline in the real housing price index to 2015 levels was found to translate into only a 0.002 rise in the total fertility rate. Analysts attributed this to the data not reflecting the sharp rise in housing prices since the COVID-19 pandemic.

South Korea’s plummeting total fertility rate has been a source of alarm around the world. In a Dec. 2 column entitled “Is South Korea disappearing?” New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote, “A country that sustained a birthrate at [South Korea’s current] level would have, for every 200 people in one generation, 70 people in the next one, a depopulation exceeding what the Black Death delivered to Europe in the 14th century.”

He also quoted a Statistics Korea projection, which stated that in the most pessimistic scenario, the South Korean population could fall below 35 million by 2067.

“[T]hat decline alone may be enough to thrust Korean society into crisis,” he wrote.

By Lee Jae-yeon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

Most viewed articles

- 1Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 2Trump asks why US would defend Korea, hints at hiking Seoul’s defense cost burden

- 3At heart of West’s handwringing over Chinese ‘overcapacity,’ a battle to lead key future industries

- 4[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- 5Fruitless Yoon-Lee summit inflames partisan tensions in Korea

- 61 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 7Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023

- 8AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 9First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 10Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report