hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Wage gap between large corporations and SMEs in S. Korea worse than in advanced countries

Wages for workers at South Korea’s large corporations are up to 50% greater than those for workers at large corporations in the US, Japan, and France, research findings show.

An alternative approach was also proposed for relieving wage polarization between large corporations and SMEs, which involved both large corporation unions and chaebols abandoning their respective strategies of maximizing wages and dominating the market for high-paying positions.

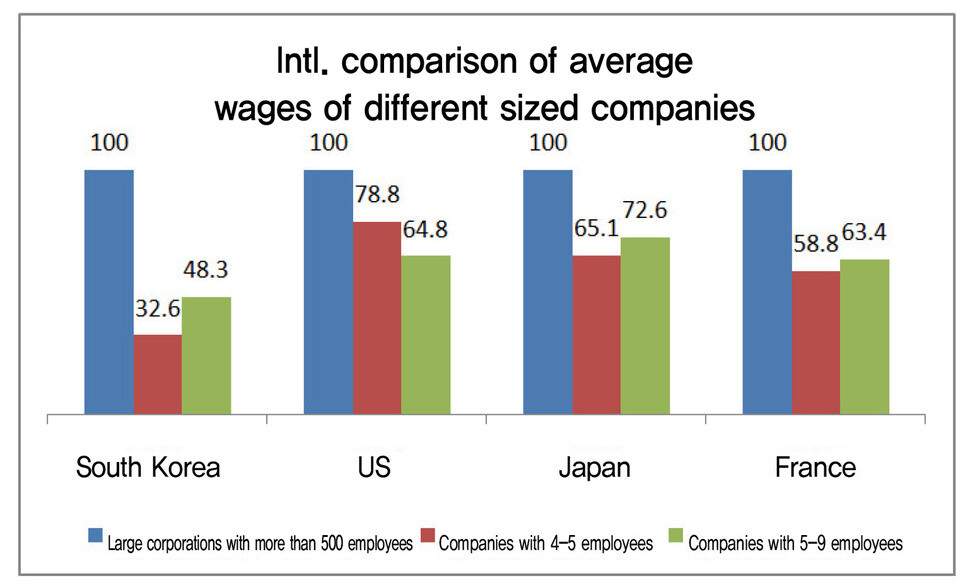

Presenting at a policy debate organized by the Economic, Social & Labor Council (ESLC, Chairman Moon Sung-hyun) on the topic “Relieving Polarization and Creating High-Quality Jobs” at the Seoul Press Center on Nov. 26, Noh Min-seon, research fellow at the Korea Small Business Institute (KOSBI), explained, “If the average monthly wages per person for workers at a South Korean large corporation with 500 or more employees [in 2017] is set at 100, then wages for companies with one to four and five to nine employees respectively amount to 32.6% and 48.3%.”

“In contrast, the respective percentages were 78.8% and 64.8% for the US [in 2015], 65.1% and 72.6% for Japan [in 2016], and 58.8% and 63.4% for France [in 2015], which means that the wage gap between large corporations and SMEs is greater for South Korea than for the advanced economies,” he continued.

Noh also noted, “The average per capita wage for [all] employees in South Korea is US$3,302, which is 78.6% to 94.2% of the levels in the US (US$4,200), Japan (US$3,504), and France (US$3,811).”

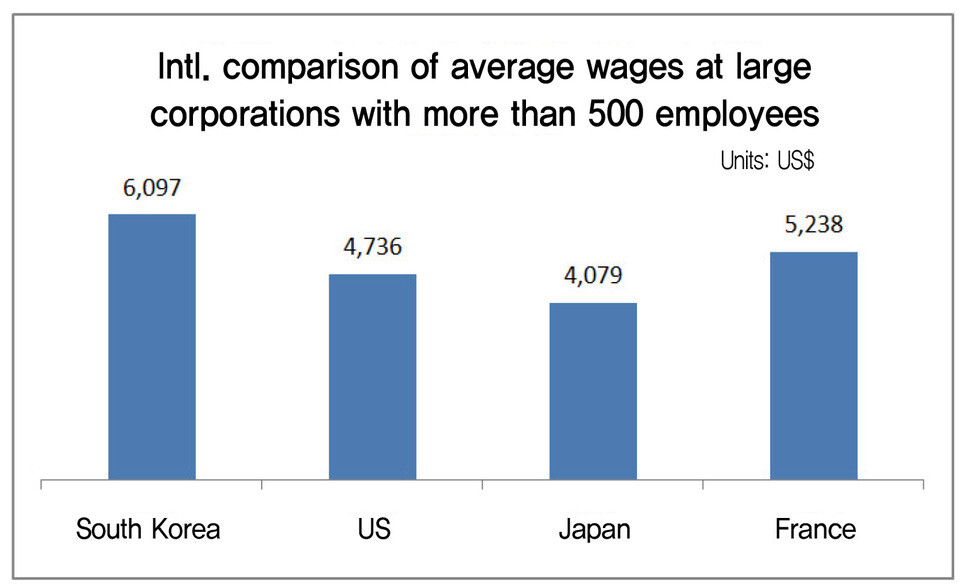

“In contrast, the average monthly wage for a South Korean employed at a large corporation with 500 or more employees was actually higher at US$6,097, which is 116.4% to 149.5% of the averages in the US (US$4,736), Japan (US$4,079), or France (US$5,238),” he explained.

Average wages by country were calculated in terms of purchasing power parity, taking the cost of living for that country into account.

Though criticism has been leveled at the high wages of regular employees at some of Korea’s chaebol amid the increasing wage gap between South Korea’s conglomerates and its small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), this represents the first international comparison of conglomerates with 500 or more employees.

“This is an empirical demonstration that the wages of employees at Korea’s chaebol are higher than at conglomerates in advanced countries such as the US and Japan. The main beneficiaries of the unequal structure between the conglomerates and the SMEs are the regular workers at the conglomerates,” said Jeong Seung-guk, a professor at Joong-ang Sangha University, who participated in the debate.

“43% of South Korean workers are employed at small companies with fewer than 10 employees. The income gap is more severe in South Korea than in advanced countries, where workers at small companies make up a smaller share of the workforce,” said Noh Min-seon.

In order to redress the income gap between conglomerates and SMEs, suggested Cho Seong-jae, head of research into labor and management relations at the Korea Labor Institute, the labor movement (which largely consists of regular workers at conglomerates) has to give up its strategy of wage maximization, while some chaebols need to abandon their strategy of cornering high wages.

“The labor unions need to adjust their wage-maximization strategy and instead adopt a strategy of wage standardization or ‘solidarity wages.’ They should also take into consideration not only wages but also employment stability,” Cho said.

“Employers should also reduce the wage gap through arbitration with the unions as in the case of Japan and make an effort to build a tolerant and integrated employment and labor relations system that’s based on employment stability.”

Wage reinforces two-tier labor market and reduces potential for innovation in economy

“The worsening of the wage gap between conglomerates and SMEs is reinforcing a two-tier labor market. The top tier of the labor market consists of regular employees, conglomerates and public companies with good working conditions, while the bottom tier consists of irregular workers and SMEs, and these two tiers operate according to different principles,” Cho said.

“Conglomerates only employ a small number of regular workers while taking advantage of low-wage workers on the outside by outsourcing non-core operations. They also use price hikes to constrain SMEs’ payment capacity, which makes it impossible for workers at SMEs to receive high wages. This pushes Korean society into a vicious cycle of lower quality employment and a widening wage gap, which damages social integration and impedes the movement of labor and other resources. The result is less possibility for innovation and a lower growth potential in the Korean economy.”

This debate was organized with the goal of achieving the key goals of creating good jobs and addressing the polarization of society. It was held shortly after the Economic, Social and Labor Council was launched on Nov. 22 to foster social dialogue between labor, management and the government. The debate featured the publication of the findings of a commission established this past June to tackle polarization by creating good jobs.

If the Economic, Social and Labor Council reflects the findings of this policy debate in upcoming social dialogue, it’s likely to ask for concessions from the labor and management at conglomerates on the one hand and from SMEs and irregular workers on the other hand.

During an interview with the Hankyoreh back in March, Ha Bu-yeong, head of the Hyundai Motor chapter of the Korean Metal Workers' Union, suggested an approach to solidarity wages in which the workers at conglomerates get small raises and irregular workers and SME employees get large raises. “If we’re to reduce the wage gap, the Hyundai Motor labor union will need a change of direction,” Ha said.

By Kwack Jung-soo, business correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 5Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 6N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 7Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 8Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 9N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 10[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father