hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Let’s stop looking at women athletes through lens of misogyny

“Kang Cho-hyun, the silver medalist in the air rifle event at the Sydney Olympics, is extremely popular — and pretty, too.”

“Ki Bo-bae has won two events in archery. This ‘archer with a pretty face’ is here with us today.”

“Koreans now view Yeon-jae as something of a cherished ‘little sister.’”

“The beauties on the volleyball team are enjoying soaring popularity.”

These lines appear in a scene from a documentary on athletes on Korea’s national team that was broadcast on the KBS show “Docu Insight” on Aug. 12.

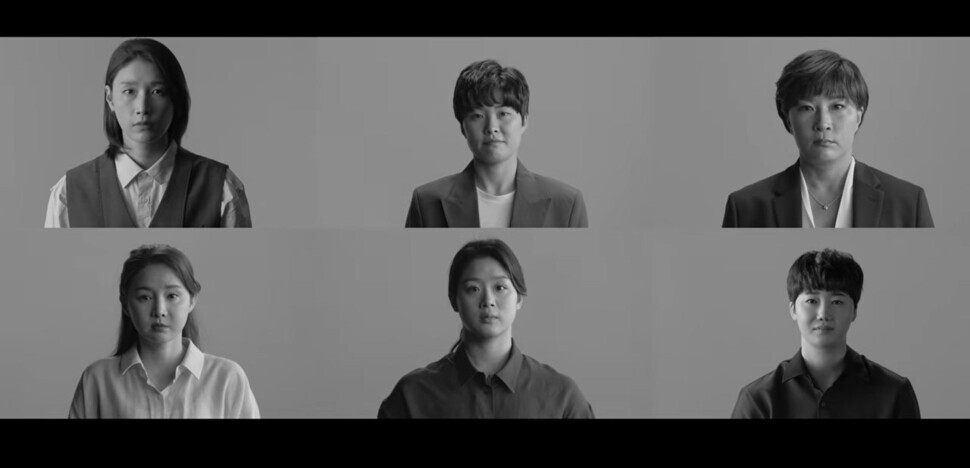

The producers of the documentary dug into the TV channel’s archives to find examples of commentators paying more attention to women’s physical appearance than their athletic ability. The documentary is at once a testament to the long history of such discrimination against female athletes, as well as a confession and penance for KBS’ own complicity in that history.

Following that archive footage, the camera turned to Kim Yeon-koung, one of Korea’s best-known volleyball players.

“They always call us ‘beauties’ and refer to us as the ‘squad of beauties.’ But no one refers to male teams as a ‘squad of hunks,’ you know?” Kim said with a sad smile.

“The reason that bothered me is that it always seems like physical appearance is the first thing mentioned about female athletes. The first thing they ought to talk about is our talent.”

It’s widely known that women made up 49% of the athletes in the Tokyo Olympics. That parity wasn’t achieved until 125 years after the first modern Olympics when not a single woman participated.

Nevertheless, men still account for an overwhelming percentage of coaches and members of the International Olympic Committee. The documentary about the national team cites the genders of athletic leaders registered with the Korean Sport & Olympic Committee: 22,213 men and 4,386 women.

The producers ask Kim On-a, a female handball player on the national team, why there aren’t more female coaches in handball, considering that women have won more medals in the sport.

“It just seems like there are a lot more men. Most of the coaches for business handball teams are men, so there are fewer coaching options for women,” Kim said.

“To be honest, I didn’t give it much thought when I was younger, but now that I’m older, I often wonder why the women who’ve won medals don’t take leadership roles and whether there aren’t any spots for them.”

The number of coaches isn’t the only difference. Women tend to make less money and receive less support than men even when they have similar careers in the same sports.

Ji So-yun, a South Korean who plays for Chelsea FC Women — part of the UK Football Association Women’s Super League, assumed that her games would take place at Stamford Bridge, Chelsea’s home stadium, but was shocked to find herself kicking the ball around an empty lot in the neighborhood. She recalled asking the team to provide more support.

Park Se-ri, coach of the national golf team and an icon of Korean golf, said she’d been stunned by the gap in prize money between men’s and women’s golf tournaments. Kim Yeon-koung remembered being angry when she heard that the salary cap had been frozen for female athletes but steadily increased for male athletes.

The root of this structural discrimination is the tendency to view female athletes as “female” rather than “athletes.”

The documentary played a section of video from the 2016 Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. While watching a swimmer whose performance had improved around the time of her marriage, the commentators glibly suggested she was benefiting from “the love of her husband,” who happened to be her coach. The comments suggested that the swimmer hadn’t improved because of her own diligent efforts, but because of help from her husband.

Five years have passed since then, the situation doesn’t seem to have improved very much, as can be seen from “The Girls Who Hit Goals,” a program about women’s soccer on SBS, another major Korean broadcaster. When Myeong Seo-hyeon aggressively breaks through the defense and goes on the attack, announcers Bae Seong-jae and Lee Su-geun said, “She must have learned that from her husband,” referring to famous soccer player Jong Tae-se. They said the same thing about Shim Ha-eun — wife of retired football player Lee Chun-soo — when she made a good kick.

Foregrounding a man’s help over the woman’s individual effort naturally undervalues the time she spent improving her skills.

Sports has always been a series of attempts to overcome one’s own limitations and the eyes of the world. But female athletes have had to fight against even more prejudices and restrictions simply because of their gender.

Along with faithfully recounting female athletes’ lonely struggle to change this reality, the documentary eloquently conveys the importance of gender equality in sports — a goal that remains unachieved.

The documentary offers a montage of clips that make its purpose clear. The montage begins with a clip of Park Bong-sik, the first woman to represent Korea in the Olympic Games, in London, in 1948.

The final clip shows An San, a Korean archer who won three gold medals in this year’s games. Despite that splendid achievement, An has faced harassment online by people prying into her politics and trying to figure out if she’s a feminist based on her hairstyle and the fact that she wears a badge to honor the memory of the victims of the Sewol ferry accident.

A website set up to figure out women’s feminist leaningsOn the very day that KBS aired the documentary about the national team, a certain website triggered a controversy online.

Unfortunately, it’s already routine for celebrities to be subjected to ideological scrutiny and asked to declare whether or not they’re feminists because of their words, actions, clothing, hairstyle, and reading choices. Now, for the first time, a website has been set up for that explicit purpose.

This crude website, whose founder claims to be a man in his twenties, gauges the feminist status of famous people in various jobs — including singers, actors, announcers, politicians, and writers — under arbitrary criteria and labels them as “suspected,” “confirmed,” or “vanguard.”

I’m not going to write the name of the website here because I don’t want to give its founder the satisfaction of getting attention.

This is a time when even athletes who pinned the Korean flag onto their chest for the Olympics can’t dodge cyberbullying, ideological prying, and unwelcome comments about their physical appearance. And now, a self-styled feminist detector is scoring people’s ideology on an arbitrary scale, egging on a witch hunt and even more harassment online.

Perhaps these two incidents on Aug. 12 offer the best explanation of why we all need feminism. We need it so that people’s efforts and achievements aren’t judged differently according to their gender and so that we can all be treated with human dignity.

By Lee Seung-han, TV columnist

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 3[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 4Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 5Historic court ruling recognizes Korean state culpability for massacre in Vietnam

- 6Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 7Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 8[Guest essay] How Korea must answer for its crimes in Vietnam

- 9Story of massacre victim’s court victory could open minds of Vietnamese to Korea, says documentarian

- 10Historic verdict on Korean culpability for Vietnam War massacres now available in English, Vietnames