hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] The great Chinese transformation and its lessons for S. Korea

Checks and balances are a key principle of the separation of powers. They are also a basic principle for ensuring the soundness of the social economy.

Without checks and balances in place, it becomes impossible to prevent government authorities, business, and construction and engineering interests from teaming up to monopolize power and resources, leaving society to foot the bill.

How do we institutionalize the principles of checks and balances? This question serves as a lens we can use to examine the different forms of capitalism in the world today.

First, checks and balances can be established as labor develops into a powerful force that can then rein in capital’s ruling privileges. This has been the path in Europe, as exemplified by countries like Germany and Sweden. But in many parts of the world, labor remains weak.

A second approach is to create an open market economy based on powerful antitrust mechanisms. By distributing economic authority itself, this approach allows for equality of opportunity and makes it easier for losers to bounce back. This distributed capitalism approach has been the path in the US.

A third path lies in a strong state that uses its regulation and adjustment powers to guide capital while controlling its privileges — East Asia being the prototypical example.

Within this category, we see some cases where the state fosters businesses while continuing to bridle them, keeping a tight grip on the reins (China), and others where the state drops the reins entirely and allows its own actions to be dictated by big business interests (South Korea).

How has South Korean capitalism gone about institutionalizing the principle of checks and balances — through strong labor, through the distribution of economic authority, or through a strong state? In a situation where labor, land, housing, currency and finance have already become deeply commercialized and the social economy has become profoundly unequal and inequitable, what power exists to ensure checks and balances by establishing a protecting countervailing force against the self-indulgent freedoms of vast conglomerates and wealthy asset holders?

That is the fundamental question I find myself asking as I look anxiously at the holes punctured in South Korean capitalism in the wake of the candlelight revolution.

By way of comparison, I’d like to talk a bit more about the path adopted by our neighbor China on its way to capitalism.

China’s transformation pathThe Chinese model is often regarded as a variant of the East Asian developmental state. This makes some degree of sense, but I also think it’s only half right.

There are similarities: the late-starter approach that has made broader use of the benefits of external openness over any kind of experience; the way that state-driven market management has created a system of government-private sector cooperation based on the encouragement of corporate investment, financial controls, and conditional support; the way in which political strides by the working class have been blockaded; and the way in which the fundamental imbalance in the resulting class structure furnishes fertile soil for doing business.

But China is also a country where an autocratic state one in the same as the Communist Party exercises enormous authority and guides the workings of capitalism. The state ownership rate there is over 30 percent.

Other key characteristics of China include the very high level of autonomy enjoyed by local governments and the intense competition between regions; prolific entrepreneurial and innovative activities from the bottom up; and a very high rate of foreign direct investment.

The basic framework of the “new China” model was put in place through a roughly 20-year transition process, with key turning points coming with the country’s decision on a course of “reforms and openness” in 1978 and Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992.

The origins behind this vast and dramatic transition include nearly all the same light and shadow that Chinese state capitalism exhibits today as it stands at a new crossroads. The 20-year shift can be divided into two phases: “reforms without losers” in the 1980s, and “reforms that create losers” in the 1990s.

During the first phase, China opted for a gradualist experiment that contrasted with the Russian “shock therapy” approach. This was later seen as having been crucial to the success of China’s transition.

Wu Jinglian, a professor who is considered one of China’s foremost institutional economists, has said it would be more appropriate to characterize this approach as an “organic development” strategy, rather than gradualism.

Under this strategy, the most crucial order of business is to form favorable conditions for the private sector to grow up from below. In other words, promoting privatization is by no means a priority. In the first phase, everyone’s a winner.

In the 1990s, China eventually reached the second phase of reforms that create losers. More precisely, it entered the stage of capitalism reforms with “Chinese characteristics.”

This included the adoption of the Company Law. As state-owned companies were transformed into corporations and restructured, they came face-to-face with rigid budget constraints that forced efficiency on them. Over the decade beginning in 1993, around 28 million workers were laid off.

The dismissed workers received three years of support for living expenses, but no stock in the companies. They also lost the social security benefits, including housing and healthcare, that the previous unit-based system had granted them.

The larger mass of workers thrown defenselessly into the new urban labor market included “nongmin gong” — migrant workers from rural communities — whose civil rights had been stripped away. Their low wages provided a base that shored up the cost competitiveness of the country’s miraculous accelerated growth, but they were barred from reaping social security benefits under a dual urban/rural structure of discrimination based on household registration status.

As Karl Polanyi noted, the commodification of land and housing is one of the two key aspects of the great transformation from community toward capitalism, the other being the commodification of labor.

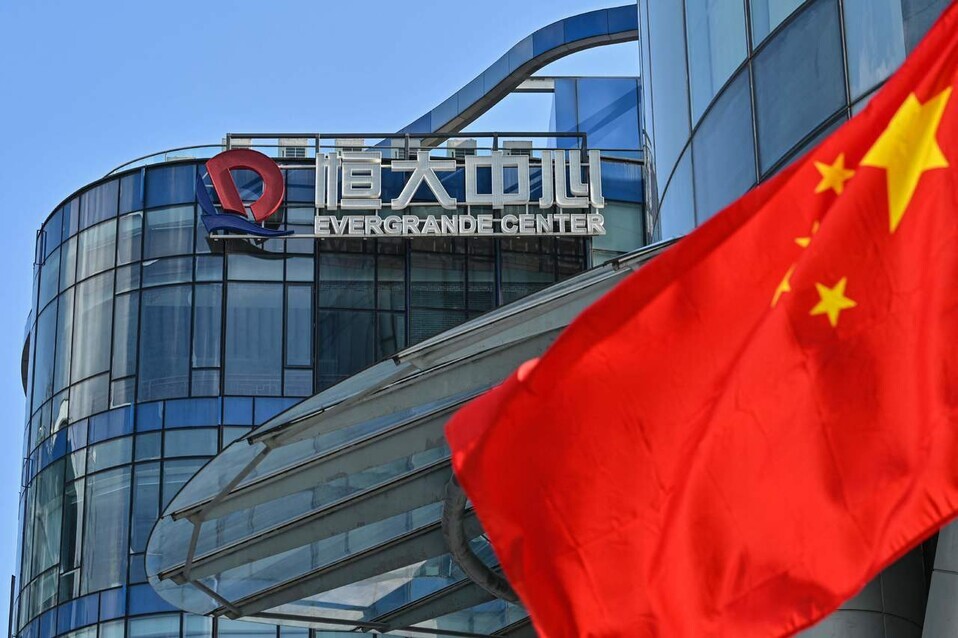

How do we account for the “fang nu” (slave to the house) phenomenon — where housing prices are soaring and people are struggling to repay their loans in a country where land is nationalized? How do we explain the bankruptcy crisis facing Evergrande, a massive real estate development company?

According to researcher Cho Sung-chan, the roots of the issue lie in the “churang” system of land-usage right transfers. As a means of acquiring funds, local governments have transferred land to developers, appropriating it at a low price after a one-time land lease (usage fee) payment.

The effect of this has been developers’ privatization of rent, i.e., the rapid rise in land value during the usage period. The combination of the land-usage transfer system and the commodification of housing has resulted in a system where the rents from rising housing values revert to the owners of the housing.

It’s quite a baffling paradox. This is a country that has been through the Cultural Revolution, yet one where workers are cast into the market without any share of assets or joint decision-making rights, and where rents are privatized through the commodification of land and housing.

The prevailing explanation for this has been China’s strategy of establishing a comparative advantage in the global market while attracting foreign capital. But is that all there is to it?

Signs of change on the horizon?With its focus on low wages and minimal welfare, China has opted for an intensely market-focused approach driven by investment, exports, and real estate development. The Chinese model of three-way cooperation among a strong state, business and financial controls has given rise not only to miraculous accelerated growth, but also accelerated inequality while leading to an extreme imbalance between excessive investment and inadequate consumption.

In addition to driving growth and success, the party/state dictatorship has also functioned to wall off and smother the resulting structural contradictions.

Recently, the Xi Jinping administration has exhibited signals that it may be leaving behind its longstanding approach of imbalanced development.

It has come out with a new development vision of mutual support between the domestic and international sectors, with an emphasis on expanding the domestic market. It has also stressed “common prosperity,” working to relieve the extreme inequalities and boost social welfare while regulating big tech monopolies and indiscriminate real estate development.

It remains to be seen what these changes will entail, and what will become of China’s “double movement,” to borrow the words of Polyani. But the Xi administration does seem to have a grasp of what the current zeitgeist is and what the state must do.

China and the US, the world’s two major powers, have embarked on a competition of reforms to inequality and inequity.

It’s unfortunate, then, to see how the South Korean government has lost sight of the opportunity afforded by the candlelight revolution, and how it has started to regress — citing the “national interest” as a reason for freeing chaebol leaders implicated in government influence-peddling, while cutting taxes for the wealthy.

South Korea finds itself once again in a transition trap. Perhaps the recent scandals involving preferential treatment in the Daejang development project and the prosecutors’ alleged incitement of criminal complaints against pro-ruling party figures can inject a bit of new momentum.

By Lee Byeong-cheon, professor emeritus of Kangwon National University

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

Most viewed articles

- 1New sex-ed guidelines forbid teaching about homosexuality

- 2OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 3[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 4Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 560% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 6Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 7Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 8[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 9Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 10Inside the law for a special counsel probe over a Korean Marine’s death