hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Guest essay] The extinguishing of the solitary splendor of Korean democracy

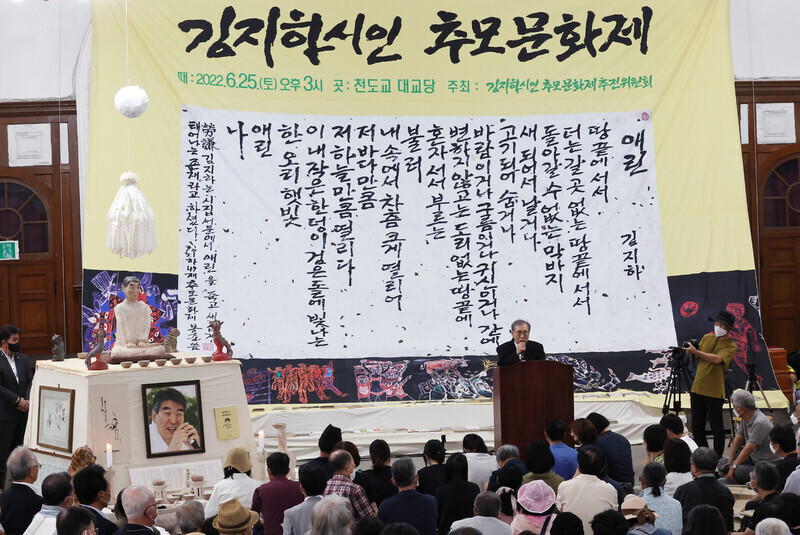

After hearing the news that a cultural festival was held to commemorate the 49th day after the death of poet Kim Chi-ha, I cracked open Kim’s collection “With a Burning Thirst” for the first time in many years.

In the era of dictatorship, amidst “the long, long shrieks of persons unknown,” the “sounds of groans, of wails, of sighs,” and the “bloodied faces of friends dragged away,” the poet saw a “solitary splendor” by the name of Democracy.

But I’ve come to wonder if we today still see democracy as something so resplendently beautiful as Kim did.

These days, we’ve grown accustomed to talk of the decline and the end of democracy, its corruption and its crisis. However, to regard democracy as this quasi-sacred thing that must be saved or protected from some threat can actually end up undermining reflective democracy that introspects on its own weaknesses and dangers.

Democracy is not a generic term for all good, beautiful and just things. In fact, democracy suffers from paradoxes and antinomies, and can sometimes even help generate the very enemies of the system itself.

Immediately after Korea’s democratization, there were several urgent tasks of the times that needed to be carried out for democracy to survive here.

The first task was to stop attempts to overthrow the democratic system which would lead to the revival of the dictatorship. Second, steps needed to be taken to prevent the military and intelligence agencies, which had been the organizational footing for dictatorship, from intervening in politics again. Third, political competition had to be invigorated and the power of voters increased so that the ruling system of dictatorships could not be extended through elections.

Those were the key tasks for the consolidation of democracy in the narrow sense of preventing a return to dictatorship. In the process of crossing this first threshold of democracy, Korean society fervently pursued the ideals of civilian control, electoral democracy, and participatory democracy. The goal was to control the military through the rule of law, determine power by the choice of the people, and revitalize democracy through civic participation.

However, there were other great risks, such as the dangerous growth of prosecutors’ power, abuse of power by elected officials, and political participation that boiled over.

This new reality began raising deeper questions about democracy. Are the winners of elections abusing their power? Was there an unelected power behind the curtain calling the shots? Can the mistakes of one power be reprimanded by yet another power? Is the political participation of citizens actually helping democracy mature?

The series of events that culminated in the candlelight protests of 2016-2017 and the impeachment and imprisonment of former Presidents Park Geun-hye and Lee Myung-bak, were above all verdicts reached by the people and the law regarding the abuse of power, political collusion, issues regarding un-elected people’s meddling in politics, and the privatization of state power.

But along the way, other risks arose. Namely, the growth of the prosecution as a political force, the popularization of civic activism, and the deepening of confrontational politics and political polarization.

The Moon Jae-in administration and the Democratic Party had their own calls of the times to address, but instead, they ended up exacerbating these problems. Prosecutors were used in the politics of eradicating corruption, elected officials actively pushed for prosecutorial reform, and an alliance was formed between politicians and supporters who believed in the idea that elected officials could do whatever they wanted.

The Moon administration sought to fight the longstanding enemies of democracy, but instead became a part — and even a cause — of the problem.

The administration of Yoon Suk-yeol was born against the background of dissatisfaction with this situation. It’s difficult to make predictions about what democracy will look like in the Yoon era. But speaking in the present, it’s been difficult to detect any desire to strive toward a higher level of democracy.

Rather, there are concerns that the situation will relapse to the era prior to impeachment. This also means that there is a risk that even the political imaginations of the Democratic Party and the progressive camp will backslide.

During the Moon Jae-in administration, the calls for the political independence of prosecutors reached a fever pitch, but now the government and political landscape are filled with prosecutors, and the line between elected and non-elected powers has all but disappeared.

In addition, those on the margins of power, such as opposition parties, police, labor, civil society, youth, women, and local governments, are excluded or considered subject to control. The long-standing problems of Korean politics, such as the concentration of power, blind faith in bureaucratic rationality, and hegemonic politics centered on vested interests, are rearing their heads again.

There is also concern that the forces that undermine democracy will flourish within society. Hatred of democratization, the left, Jeolla provinces, women, feminism, sexual minorities, migrants, the disabled, and welfare recipients are widespread online.

There are huge far-right online communities on KakaoTalk and YouTube, and massive “post-truth” networks where radical fake news is constantly being circulated. All these generate public opinion “democratically.”

The dazzling version of democracy that Kim Chi-ha had written about — the one that had people shout “Democracy! Mansei!” with “trembling hands and trembling hearts” — is now dead.

What we need now is to ask ourselves about the meaning of the essential elements that make up democracy, such as the people, participation, public opinion, sovereignty, freedom, and the rule of law, and to rewrite democracy once again.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 3AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 4[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 5Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 6Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 7Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 8Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 9The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 10Yoon says collective action by doctors ‘shakes foundations of liberty and rule of law’