hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Guest essay] Were Japan to honor Kim Hak-soon, survivor of comfort woman system, on a stamp

By Kim Hyeon-a, writer and head instructor at RoadSchola

There was a time when stamp collecting was all the rage. It must’ve been before the 1940s, when sending letters was the popular way of sending greetings.

There were some people who only collected stamps that portrayed specific things, say birds, flowers, or fish, while others were focused on accumulating stamps from across the world.

When special stamps were issued to commemorate important anniversaries or historical days, hardcore collectors would line up to buy those stamps.

Those who collected stamps with postmarks carefully removed stamps from envelopes and stored them away safely.

With the advent of email and as social media soon became the most common method of communication, I had no need to handwrite letters, which meant that there was even less of a need to buy stamps. I did, however, buy a stamp for the first time in a very long while in Hawaii last summer.

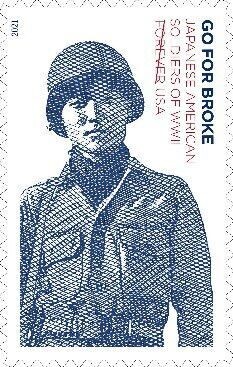

It was a stamp issued by the US Postal Service that featured a young Asian man, just grown out of boyhood, wearing a military uniform.

The words “GO FOR BROKE” adorned the side of the stamp, and “JAPANESE AMERICAN” was written below the boy. GO FOR BROKE was the slogan of the 442nd Infantry Regiment, a fighting unit composed of Japanese American soldiers during the Pacific War.

When the Pacific War broke out in December 1941 with Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, there were 120,000 or so Japanese people living in the western US. The first immigration point for the Japanese was Hawaii. In 1868, during the Meiji Restoration, 153 Japanese people ventured to Hawaii to work on sugar cane farms. This was the beginning of Japan’s overseas immigration.

The next year, in 1869, 40 Japanese people moved to California with permission from the Japanese government. Immigration was the only way for people who had lost everything in Japan to start anew.

During the Meiji Restoration, many farmers were either suffering from extreme poverty due to various taxes that were forced upon them or abandoning their farms and becoming wanderers. After Hawaii was annexed to the US (1898), more than 12,000 Japanese immigrants living in Hawaii moved to the western United States en masse, once again packing their bags in search of a place with higher wages than Hawaii.

Japanese immigrants worked in places like canning factories, wood mills, railway construction sites, and farms. With the increase of Japanese immigrants, the immigration of Japanese people to the US was legally prohibited in 1924, not long after the Chinese Exclusion Act had been put in place.

The immigration of Chinese people to the US took place earlier than that of the Japanese. During the California Gold Rush, many Chinese people immigrated to the U.S. between 1848 and 1855, and they later played a large part in the construction of the transcontinental railroad.

Despite providing cheap labor and struggling through toilsome, backbreaking work, Chinese immigrants soon became the target of blame by the majority of US society. American workers blamed Asian immigrant workers for lowering wages, and even excluded the Chinese workers from trade unions.

This led to the enactment of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which was the first law to ban a specific ethnic group from entering the country. With the term “yellow peril” fast becoming popular, Japanese workers were also discriminated against — for example, their children were excluded from public school education. Soon, even Japanese workers were banned from entering the country.

The attack on Pearl Harbor only exacerbated preexisting discrimination against Asians in the United States. FDR issued Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Executive Order 9066, which was born in a social atmosphere that was wary and suspicious of Asian immigrants, became the legal basis for forcibly quarantining immigrants from “hostile” countries. Most Americans strongly supported this order.

Just like that, Japanese Americans became labeled as “potential spies” or “potential enemies.” Even if one was born in the US, educated at an American school, worked at an American company, and was even an American citizen, one could be fired from their job and confiscated of all their property for being of Japanese descent. Then, they were sent to concentration camps, due to speculation that they might fraternize with the enemy, Japan, to cause civil unrest or even war.

During that process, the 442nd Infantry Regiment was formed. Except for the battalion commander and three other executives, the unit was made up of second-generation Japanese immigrants from Hawaii or the US mainland.

The Japanese American unit fought for the victory of its homeland, the US, going for broke. They considered themselves Americans because they were Americans. They willingly risked their lives to prove this fact. The person on the stamp issued to commemorate the 442nd Infantry Regiment was a second-generation Hawaiian immigrant, Yamamoto. The year this stamp was issued, 2021, the White House announced an official government apology for Executive Order 9066.

“Seventy-nine years ago today, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which stripped Japanese Americans of their civil rights and led to the wrongful internment of some 120,000 Americans of Japanese descent. In one of the most shameful periods in American history, Japanese Americans were targeted and imprisoned simply because of their heritage. Families were forced to abandon their homes, communities, and businesses to live for years in inhumane concentration camps throughout the United States. These actions by the Federal government were immoral and unconstitutional — yet they were upheld by the Supreme Court in one of the gravest miscarriages of justice in the Court’s history,” read President Joe Biden’s official statement.

He went on to state that “America failed to live up to our founding ideals of liberty and justice for all, and today we reaffirm the Federal government’s formal apology to Japanese Americans for the suffering inflicted by these policies. The internment of Japanese Americans also serves as a stark reminder of the tragic human consequences of systemic racism, xenophobia, and nativism.”

“Reaffirm” here indicates that an apology has already been given. In 1988, Ronald Reagan officially apologized calling the executive order “a mistake” swayed by racial prejudice and wartime hysteria. Barack Obama stated in 2015 that the internment of Japanese Americans was one of the “darkest chapters” in American history, saying, “We succumbed to fear, we betrayed not only our fellow Americans but our deepest values.”

In their agreement on the issue of “comfort women” drafted into sexual slavery by the Japanese military, South Korea and Japan used the phrase “final and irreversible.” The Japanese prime minister at the time, the late Shinzo Abe, said, “We cannot saddle our children and future generations with the duty of having to continually apologize.”

While the US government’s repeated apologies have been directed at Japanese Americans, they also signal its resolve at the community level to reflect on the past and ensure that similar things do not happen in the future. Continually referring to examples of historical misdeeds is also a way of warning against and preventing fascism among our own ranks.

The reason I made a point of purchasing that stamp I found showing a Japanese American soldier is because of my hope that someday Japan might come out with its own stamp commemorating Kim Hak-soon. A stamp in her memory would be a symbol of our children and later generations sharing a common memory, devising common values, and working together to create peace. I look forward to a day in the not-too-distant future when the Japan Post issues its first stamp in Kim Hak-soon’s honor.

* Kim Hak-soon was the first person to speak out and identify herself publicly as a survivor of sexual slavery by the Japanese military.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 1Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 2[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 3Bills for Itaewon crush inquiry, special counsel probe into Marine’s death pass National Assembly

- 4Trump asks why US would defend Korea, hints at hiking Seoul’s defense cost burden

- 560% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 6S. Korea discusses participation in defense development with AUKUS alliance

- 7[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 8Korean firms cut costs, work overtime amid global economic uncertainties

- 91 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 10[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis