hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Korea must reckon with its atrocities in Hà My

One day in February 1968, 6-year-old Nguyen Thi Bon was eating breakfast with her mother, brother and two sisters in Hà My village in the Vietnamese province of Quảng Nam when soldiers wearing camouflage uniforms appeared and began rounding up the villagers. Then, they suddenly opened fire.

At that moment, Nguyen’s mother hugged her daughter while her older sister clinched the youngest child in her arms. Nguyen’s mother and older sister were both killed by flying bullets. The youngest child, only 3 years old, began to cry in shock, but a grenade came flying over the sound of her tears. Nguyen awoke in a hospital with her head cracked open. Her parents, brother and sisters had all been killed.

Three-year-old Dang Thi Ka doesn’t remember that day. She was pulled into the arms of her grandmother who died of a gunshot wound while holding her. Dang lost her grandmother, mother and four sisters that day. Eleven-year-old Nguyen Thi Thanh was ordered by soldiers to follow the adults into an air-raid shelter. Then a grenade came flying through the door. After it exploded, the air was filled with smoke and blood. Nguyen went deaf in her left ear and had shrapnel stuck in her waist. Her mother and 8-year-old brother were killed.

In total, 135 people were slaughtered in Hà My village that day. Fifty-nine of them were under the age of 10. The residents say the soldiers were Korean. They had been on good terms with the villagers, frequently offering chocolate or snacks. The reason why the soldiers suddenly turned on the village was unknown, and remains a mystery to this day. It is possible the soldiers were suspicious of the locals after taking damage from the Viet Cong.

Fifty years have now passed. The surviving children who lost their mothers, brothers and sisters in the blink of an eye are now past the age of 60. It was April 2022 when they submitted a petition to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea demanding an investigation into the truth about the massacre. After a year of silence, the commission decided to dismiss the application on May 24.

As for the reason, the commission stated, “There does appear to have been some likelihood of harm in the Hà My village incident. It does appear that the state bears some responsibility in connection with that issue. But there is also the potential for restitution for that harm to be received through the courts rather than the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. We will move to dismiss [this matter] as not corresponding to the scope of our Commission’s investigation subjects.”

Hopes were muted from the outset due to the 3:3 split among the full committee of members nominated by the ruling and opposition parties, with the effective casting vote to be issued by Chairperson Kim Kwang-dong, a candidate personally nominated by President Yoon Suk-yeol.

The victims gained a glimmer of hope when the villages of Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất succeeded in a lawsuit seeking state compensation from the Korean government in February. However, the truth commission has ultimately decided to sidestep the issue.

Although the victims have the formal right to request a reexamination and appeal the decision to the courts in the same way as Phong Nhị and Phong Nhất, it is unclear when the truth about that day will be thoroughly investigated.

When I was young, I remember sitting next to the record player in my parents’ room and lifting the turntable needle to play records. One of the tracks by the bandana-clad Kim Choo-ja was Sergeant Kim Back from Vietnam (1969). “Sergeant Kim is back with his stately medals / his mother dances at her son’s return / and it’s a party for the whole neighborhood.” A year prior to the release of this song and several years before young boys sang along to it, a funeral was held in a Vietnamese village.

Korea has suffered countless massacres and hardships over the years, from the Jeju Uprising and Gwangju Uprising to sex slavery and forced mobilization. But it is now time for us to face our own mistakes as well. We must not be like Japan. This does not mean stirring up the past for no reason. The war in Ukraine rages on, and war will break out again in other places in the future. But when war breaks out, the atrocities that took place in Hà My village must not be repeated. The effort we put into Hà My today will prevent another Hà My from happening tomorrow. This is why we must not allow the TRCK’s decision today to be the end of the matter.

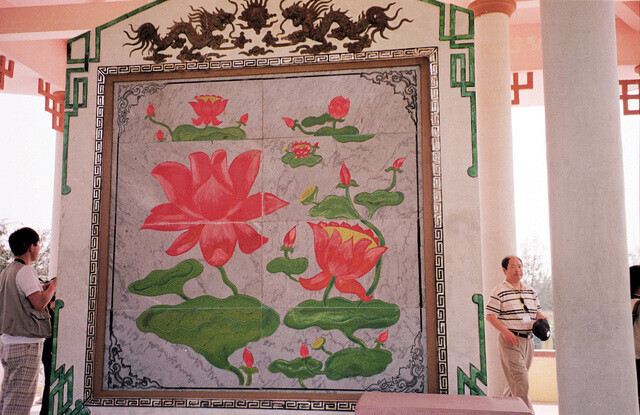

Hà My is only a 20-minute drive from Da Nang, a popular tourist destination for Koreans. The village has a monument inscribed with the names of the victims, built in 2001, with US$25,000 in financial support from the Vietnam War Veterans Welfare Center. The old epitaph contained a poem written about the massacre. When the description of the Korean soldiers as murderers caused controversy, it was covered with a lotus pattern mural. Today, the truth commission has decided to leave the truth about Hà My village hidden below this marble lotus pattern. When will it see the light of day?

[%%IMAGE3%%]Part of the covered epitaph reads as follows:

”500 years ago, the descendants of Lạc Long Quân and u Cơ crossed the Hoành Sơn Range and founded a country here. These benevolent and good-natured people bore and raised children and worked the land with plows and hoes, growing vegetables and catching fish to live off. [. . .]

In the early spring of 1968, soldiers rounded up and slaughtered the villagers. Pieces of the bodies of 135 people from 30 families were scattered everywhere, and the village was painted red with blood. The sand became mixed with bones, tangled corpses hung from the pillars of houses set on fire, and ants crawled over their burnt flesh. The bodies of elderly mothers and sick fathers lay together in the doorways. When we hastily piled up the bodies, all were ridden with bullets. The bodies were covered in pools of dried blood, and babies crawled onto the stomachs of their deceased mothers to nurse at their cold bosoms. Some children who had their mouths and chins blown off were unable to drink in spite of their thirst. [. . .]

The Koreans who had left us with so much grief came and apologized to us. We erected a memorial stone based on forgiveness, thereby opening a path for development and cooperation in our homeland. As a line of incense smoke wafts into the sky, we hope they are resting in peace on the other side.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Samsung subcontractor worker commits suicide from work stress

- 2Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 5[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 6Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?