hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] My father’s complicated relationship with S. Korea’s progressives

My father is a member of the Justice Party. He was born in Jeju in 1936. For a long time, he was a passionate supporter of Kim Dae-jung. In the winter of 1992, I went to my hometown to vote in the presidential election, and my father stayed up late into the night, unable to turn off the TV as the votes were being tallied.

“Go to bed. That was Kim Young-sam’s election anyway.”

His response was chilly.

“Get this straight. You young people have committed a grave crime against history.” I hadn’t pulled the lever for Kim Dae-jung in that election.

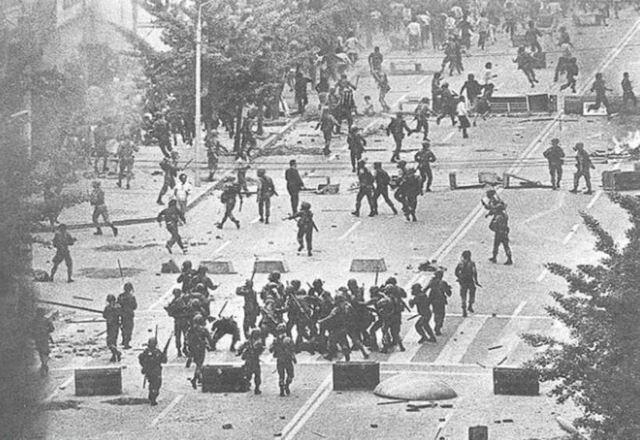

My father is a retired Presbyterian minister. He began his missionary life in the early 1960s, traveling to the mainland and attending a seminary. He met my mother, who has just begun working as a schoolteacher, and the two of them married in Gwangju. He was a minister in a farming village for over 10 years before becoming head minister at a church on the outskirts of Gwangju in the late 1970s. As zealous as other pastors in his pursuit of growth, he convinced his congregation to begin building a new church by a major road. The construction was nearing its end in the spring of 1980 when our family moved into the rectory on the church’s basement level. Less than two months later, the Gwangju Democratization Movement of May 1980 erupted.

My father went every day to the area in front of the South Jeolla Provincial Office. His face was a mixture of anger and helplessness when he came back around sunset and relayed the situation downtown to my mother.

“It looks like they’re arresting and killing everyone. They were dragging female college students off in their underwear. That’s the sort of people they are. Can those monsters really be this country’s soldiers?”

News arrived that soldiers had opened fire on the demonstrators, and the gun-toting citizens’ militia were spotted in the neighborhood. As the sun went down, gunshots could be heard all around the church.

As rumors spread that the martial law forces were planning to re-enter the city after withdrawing to its outskirts, my father sent me and my brothers to stay with my mother’s family in the Seoseok neighborhood. He was worried about hostilities breaking out at the church. At the time, the building had a four-story bell tower on top, which would have made it easy to spot martial law forces arriving from the Hwasun area. The citizens’ militia came to the church with carbines in hand. My father invited them into the underground rectory, where he offered them rice and instant noodles.

After spending a day at my mother’s house, I returned home, but my father wasn’t there. He finally arrived around lunchtime after having a look around the downtown area.

“The government employees are cooking for those murderers,” he told me. “What happened to those remaining people at the provincial office?”

The congregation grew quickly after the church was built. As the number of registered members passed 300, my father quit his job as head minister, deciding that it had become “too tough.” He began a new church and began traveling to Seoul more and more frequently as he took on a position with the human rights committee of the National Council of Churches in Korea. Printed publications on “sexual torture of female student activists in Bucheon,” “suspicious deaths of student activists drafted into the military,” and other incidents offered appeared around the house.

After the change in administrations in 1997, my father’s political preferences naturally shifted to Roh Moo-hyun. He would often grumble about how the Democratic Party politicians of the Jeolla provinces had “sold out Kim Dae-jung for their own gain.” In 2009, after both the former presidents had passed away, he began warming to the progressive parties, which had maintained a cool-headed remove.

Opening up about the Jeju MassacreIt was around this time that my father finally opened up -- with some difficulty -- about his experience during the Apr. 3 Jeju Massacre. I heard about how my grandmother had spent large sums three times to bail out my grandfather, who had been counting the days to his execution after being taken to an internment camp. He described witnessing the execution of “rebels” at a marketplace by punitive forces, which he said had become indelibly etched into his brain. Around the same time, he borrowed a copy of Kim Seok-beom’s historical novel “Hwasando (Volcanic Island)” from the local library. From time to time, he would lose himself in thought reading other books related to contemporary history that mentioned the Jeju Massacre.

They say you get more conservative as you grow older, but my father only became more radicalized over time. Two years ago, he registered for a political party for the first time in his life. It happened shortly after the suicide of Justice Party lawmaker Roh Hoe-chan. Explaining his reasons for joining, he said, “I just felt so bad. Those people were the salt of the earth.”

Speaking to my father on the telephone last week, I asked him whether he was disappointed in the general election results. He seemed serene.

“Who could have ever imagined during the Jeju Massacre or the Gwangju Democratization Movement that we’d see a world like this?”

After a brief silence, he continued.

“With history, things are always moving forward, even when it seems slow. I still feel like I let people down.”

By Lee Se-young, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 3Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 6Korea protests Japanese PM’s offering at war-linked Yasukuni Shrine

- 7[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 8‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 9“Korea is so screwed!”: The statistic making foreign scholars’ heads spin

- 10[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?