hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Culture flows like water: the rise of K-pop and S. Korea’s cultural stature

As the host of a current affairs program, I often remark that money “flows like water.” Just as water can flow fiercely with just a 0.1% difference in incline, so I believe that any attempt to artificially alter the flow of money in a single-minded pursuit of profit requires us to forgo rash interference in favor of crafting economic policy with the utmost objectivity. To this, I might also add another question: Is it only money that flows like water? So does culture.

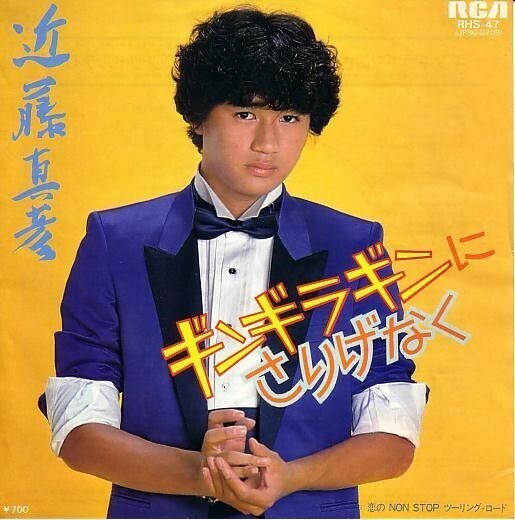

In previous columns, I have remarked on how music -- in contrast with industrial products, food, films, or literature -- is an area where we have totally spurned Japanese products. It has never been acceptable to play Japanese songs, be it under military or democratic administrations, conservative or progressive ones. But as recently as my own childhood between the 1980s and early 1990s, I encountered quite a lot of Japanese songs here and there. My oldest memory is of a dance number titled “Gin Gira Gin ni Sarigenaku,” by a pretty-boy star named Masahiko Kondo, who was wildly popular in 1980s Japan. The song was also very popular in Korea, so much so that even kids living in small coastal villages would hum its tune without its having once appeared on a broadcast.

Plagiarizing Japanese songs was once commonplaceThe same sort of thing continued after that: Japanese singers would become popular in Korea through word of mouth, whether it was rock groups like X Japan and Loudness or singing acts like Keisuke Kuwata, Tube, Anzen Chitai, and Shojotai. There was a spate of remakes by artists taking advantage of the fact that Japanese songs could not be played on the radio as is; sometimes, I heard them without knowing whether they were Japanese or not. Such tracks included “Oh My Julia” by Country Kko Kko, “Season in the Sun” by Jung Jae-wook, “Counting Our Kisses” by Hwayobi, “Snow Flower” by Park Hyo-shin, “Spring Days of My Life” by Can, and quite a few more besides. Better that they should be remade properly -- there was so much controversy over “plagiarizing” Japanese songs that I can remember complaining about how there “don’t seem to be any songs that haven’t copied Japanese ones” when I first went to work at a radio station.

That climate is gone now. These days, YouTube and streaming platforms offer us nearly unlimited listening opportunities -- yet Japanese songs remain very much a culture for a small number of fans. Back when everyone was telling me to not listen, I would sing along passionately to “Gin Gira Gin ni Sarigenaku” -- so why don’t I listen to it today, when I have the freedom to do so whenever I want? The reason is that culture flows like water. Are Japanese acts more popular and profitable in Korea, or are Korean acts more profitable in Japan? There’s no need for research. We’ve seen so many news stories about K-pop stars storming Japan’s Oricon charts and selling out the biggest performance venues that it all seems like old news. When is the last time anyone heard of a Japanese singer topping the Korean music charts or selling out Seoul’s Olympic Stadium?

As recently as a few years back when PSY’s “Gangnam Style” was enjoying global popularity, I thought it was a one-off phenomenon. I suspected that might be as good it would get. But the songs we refer to as “K-pop” have been setting new records every year. Things reached their peak this week: as of the time I’m writing this column, the name “BTS” was attached to the top two songs on the Billboard singles chart. The top two spots on this chart were once held by legendary acts like the Beatles and the Bee Gees. Blackpink has reached No. 2 on the Billboard 200 album chart, after BTS previously came in at No. 1. It’s the best performance yet by a Korean female act, and there’s no reason to believe they won’t eventually reach the top as well.

From exporter of goods to exporter of culturePeople from my age group in their 40s and 50s grew up thinking of South Korea as the “white-clad people” or a manufacturing state. Under the military administration, there were all sorts of slogans about how our only route to survival was to eventually become an exporting power. As a child, I heard a lot of talk about “Gold Tower Order of Industrial Service” commendations and “export mainstays.” Today, South Korea has reached a level of stature where it no longer needs that sort of propaganda at home or overseas. Its products lose nothing in comparison to those overseas in trade volume or quality, and the labels “made in the USA” or “made in Japan” no longer convey a sense of superiority.

And now “culture” has been added to a list of choice products alongside semiconductors, home appliances, automobiles, mobile phones, and ships. The old “Gin Gira Gin ni Sarigenaku” exemplifies the mood in 1980s Japan -- vaunting the peak of its bubble economy, oblivious of the long-term recession soon to come. The lyrics of the chorus declared, “Beautifully yet naturally / I will seduce you as I choose” -- and it really was just like that. The dazzling Japanese popular culture then enjoying its zenith arrived in South Korea despite all the efforts by the government to stop it. And now, all these years later? The K-pop wave is spreading throughout the world -- beautifully and naturally, pulling in massive amounts of foreign currency and building the national brand all the while.

It’s exhilarating, but it’s also frightening. Will the Korean Wave fade into memory like Hong Kong cinema or Japanese popular culture? They say nothing lasts forever, but I would love to see the waters of South Korean culture continuing to flow for many years without running dry. Popular culture content is like the most ideal future “foodstuff,” meeting all the conditions named by futurologists for a promising future industry: eco-friendliness, high value-added activity, and applicability with new technologies.

When it comes to our future as an exporter of culture, can’t we afford to invest 10% -- or even just 5% -- of the amount the South Korean government spent in various forms of support ushering us toward becoming a manufacturing exporter during our development days? For example -- never mind, I’ll spare the details.

By Lee Jae-ik, producer for SBS Radio

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 6Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 7[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 8Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 9Marriages nosedived 40% over last 10 years in Korea, a factor in low birth rate

- 10‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis