hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

New documentary refutes “comfort women” disinformation at the source

“I wanted to make a film that logically refutes [the distorted historical record.]”

These are the words of Lee Suk-jae, who directed the documentary film “Koko Sunyi” about victims of Japanese wartime military sexual slavery. In a recent interview, he pointed out that Japan's distortion of history is ongoing, which is why he felt the need to make the film.

Many movies, dramas, TV programs and books related to the so-called comfort women issue have been published so far, but among them, “Koko Sunyi” logically refutes the absurdity of some of the claims of Japan’s far right based on historical data.

Much of the information shared in "Koko Sunyi" is based on the Japanese Prisoners of War Interrogation Reports No. 48 and 49 published by the US Office of War Information (OWI), which contains details about the “comfort women” at the time.

Lee’s film is centered around the life of Grandmother Sun-yi, who was taken to a sexual slavery camp, also known as a “comfort station,” in Myanmar during the war.

Lee, who works as an investigative reporter for KBS, found that, among the 20 “comfort women” in Myanmar recorded in the OWI report, a woman with the surname Koko and first name Sun-yi was actually a woman named Park Sun-yi who lived in Hamyang, South Gyeongsang Province.

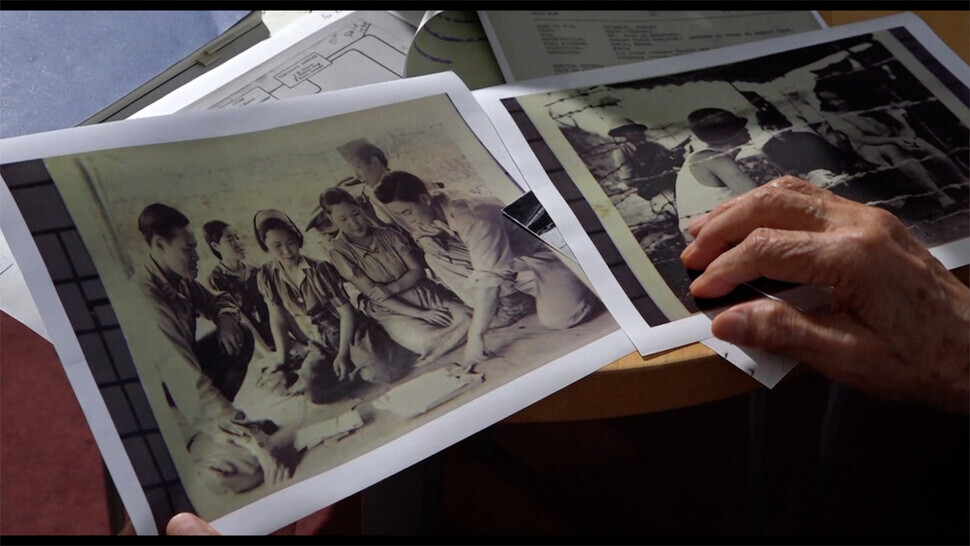

To further investigate the case, he decided to visit the descendants of Park and those of the OWI officers who wrote the report and to compare the records one by one.

According to data released by the Northeast Asian History Foundation, there were 559 “comfort stations” built by the Japanese military around the world.

Besides Korea, evidence of these comfort stations has been found in China, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand, Myanmar, Indonesia and India, but the whereabouts of many victims who passed through these places remain unknown.

Lee was able to discover the existence of Park Sun-yi, who became the protagonist of his film, by digging through old historical data and conducting comparative analyses in addition to collaborating with various institutions, organizations and broadcasting companies.

The National Institute of Korean History was the starting point for the planning of “Koko Sunyi.”

In 2018, a “comfort women” war crime investigation team was formed by the institute. It was this team that began taking a more detailed look at OWI reports No. 48 and 49.

That year, the documentary program Lee works for at KBS covered this investigation process and made a two-part Liberation Day special titled “The State Abandoned Them.”

But Lee was not completely satisfied with how the episodes turned out. Due to what he called “many problems in the production process and poor coverage,” Lee decided to dive deeper into the issue and make a film that would build off of the KBS documentary while also conducting additional, original research.

Park Sun-yi, the documentary’s titular focus, would not have been known to the world if it were not for Lee, his KBS team and the National Institute of Korean History.

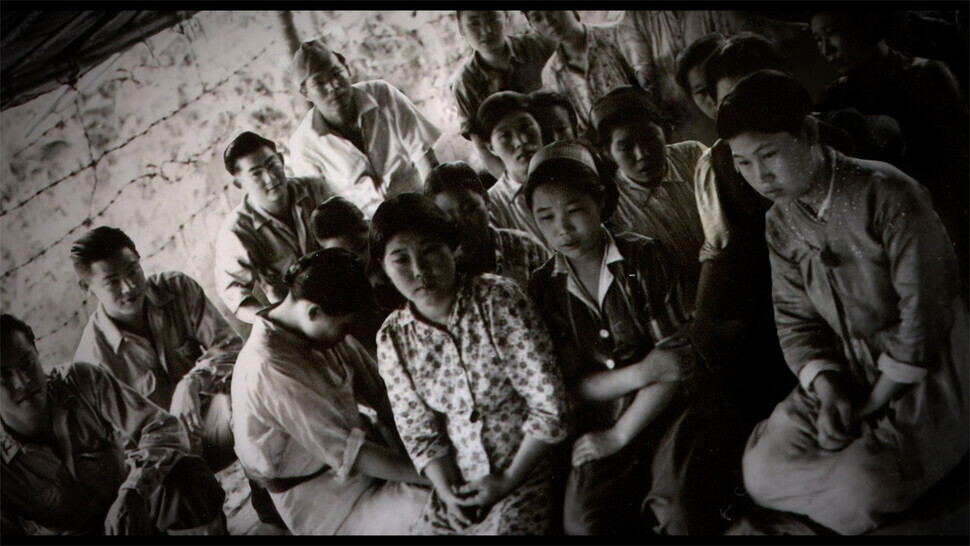

Park was one of the victims of the comfort women system who appeared in several photos found in the OWI reports.

For the film, Lee particularly focused on the contents of report No. 49, which recorded the name and address of Park.

While conducting his research, Lee said he saw that the report was “biased” against victims of Japanese wartime sexual slavery, and that the report was also “used as a basis for Japan and many far-right conservatives to attack” the sexual slavery issue.

When Lee visited the area where the former comfort station was located in Myanmar, he could immediately see how much the report had been distorted.

Report No. 49, an OWI Japanese prisoner interrogation report written by Japanese American Alex Yorichi, described the girls as “selfish,” “egotistical,” and living in “near-luxury” at the station.

“When I visited the site, it was still an underdeveloped area. What luxury would have come from such a place? Especially during a war,” Lee asked.

Lee’s suspicions were proven right when he looked up video footage from Myanmar’s National Archives. These videos showed that the location of the comfort station at the time was surrounded by rice paddies and fields. It didn’t even have a proper hospital.

Lee also personally visited the relatives and friends of Captain Won-loy Chan, who also worked on the OWI report at the time, and talked to him about his book “Burma, the Untold Story.” It was an understatement to say that depictions of the 20 “comfort women,” including Park, in his book were devastating.

Another noteworthy point about Lee’s film is that it also uncovers the voices of those who actively criticize and denounce the “comfort women” issue around the world.

“In the US, a far-right YouTuber known as ‘Texas Daddy’ has been actively critical of ‘comfort women.’ I thought there would be some kind of connection with Japan,” Lee said, also shifting his attention to Harvard University professor John Mark Ramseyer.

Last year, Ramseyer published a paper that characterized the victims of Japanese military sexual slavery as “voluntary prostitutes.”

“I figured out that the company that funded professor Ramseyer’s research is supporting far-right groups, and that these same groups are also connected to Texas Daddy in the form of sponsoring him,” Lee said.

“They continue to try to get rid of the entire chapter on ‘comfort women’ from official [Japanese] textbooks,” Lee explained.

The film also includes the scene where Lee and his team try to conduct an interview with Ramseyer.

What "Koko Sunyi" wants to show viewers is the journey of Park Sun-yi’s pain — a journey that history failed to record properly.

Park’s journey began when she was dragged from Hamyang, South Gyeongsang Province, to Myanmar. She was then unable to return to Korea even after all the indignities she suffered.

Even after the end of the war, Park was unable to return home for various reasons and ended up going to China by route of India. She eventually did come back to South Korea in 2004, and lived her final four years in her home country with her family before passing away in 2008.

However, none of her family members ever knew that she had been sent to Myanmar.

Park left this world with a story that she was unable to properly share with her descendants. Still, her final four years in Korea were warm.

“According to her daughter and grandchild, they were the happiest four years of their grandmother’s life,” Lee said.

“I think this may be the greatest pain in modern Korean history.”

By Kim Hyeon-su, former Cine 21 reporter and film columnist

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Korea protests Japanese PM’s offering at war-linked Yasukuni Shrine

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8One Hyundai worker suffers through 16 piecemeal contracts in 23 months

- 9[Photo] Migrant workers rally for labor rights

- 10Korea once again ranks near bottom of list for gender parity, report shows