hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

“Pachinko” author wants readers around world to get a taste of being Korean

“In college, when I was 19 years old, I went to a lecture with a friend. The lecturer was a white missionary from Japan, and he talked about the death of a 13-year-old Korean Japanese boy. After the boy took his own life, his parents looked at his graduation album to figure out what had pushed him to the decision, and there they found writing such as ‘I hate you because you smell like kimchi. Go back to your country. Die, die, die.’ Listening to the story, I was so heartbroken, shocked, and angry. That story stayed with me for a long time and ultimately came out into the world as the novel ‘Pachinko.’”

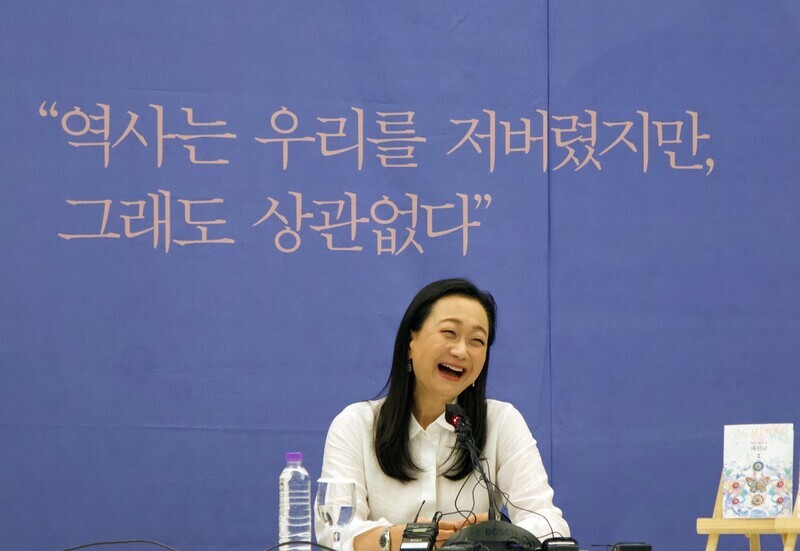

The author of “Pachinko,” the novel that garnered popularity not only in Korea but also across the world after it was turned into a drama series for Apple TV+, Min Jin Lee met with Korean reporters at the Korea Press Association building in the Jung District of Seoul on Aug. 8.

Spanning almost a century, “Pachinko” deals with the story of Korean Japanese, starting in Yeongdo, Busan, during the Japanese colonial period and ending in 1989 Japan. The novel was first published in the US in 2017, the year after which it was translated and published in Korean. Subsequently, the Korean translation went out of print in April, when the publication contract for the book came to an end, but now, a new Korean translation of “Pachinko” is available from a new publisher. The first book of the new translation was published late last month, and the second book was published on Thursday.

“History has failed us, but no matter,” reads the opening line of the novel. The previous Korean translation rendered this sentence as “History ruined us, but no matter” in Korean. In contrast, the new translation is markedly different from in terms of word choice, sentence structure, and even the structure of the entire book. “As I dedicated almost all my life into writing this novel, it’s important the book gets introduced accurately when being published in translation,” said Lee while meeting with reporters on Aug. 8, adding, “I thank my translator and publisher, as they respected my intention as the author when it came to translating and structuring the new edition.”

“I wrote ‘Pachinko’ with the conviction that I had to let the world know of what Koreans and Japanese experienced during bygone times,” Lee continued. “As I become Russian when reading Tolstoy, British when reading Dickens, and an American man slightly out of his mind when reading Hemingway, I want to turn every reader reading this book Korean.”

“In 2017 in Pittsburgh, I had my first ‘meet the author’ event since publishing this book, and 99% of the 2,000 readers who had gathered there were either white or black. There weren’t that many Asian Americans. I think there was a reason for that. You see, what I originally liked was 19th-century European and American fiction. Social realist fiction told by an omniscient narrator. But there have been more and more Korean readers at such events in the last three to four years. Korean readers come to those events and send me letters, and it’s when they tell me that they’ve finally come to understand their mothers, want to talk with their fathers, and feel proud to be Korean that I feel how meaningful and worth it it is to be an author.”

Before “Pachinko,” Lee published “Free Food for Millionaires,” a book about immigrants in the US in 2008. She said she is currently writing “American Hagwon,” the third book of her “Korean diaspora trilogy” that tackles the fervor for education among Koreans.

“Just as I used the word ‘pachinko’ as is as my novel’s title because I believed the world should know about the word, I plan to use the Korean word ‘hagwon’ as is in English because I believe the world should know about the word. This is because you have to know about this word in order to understand Koreans. This word epitomizes the reason education is so important to Koreans not just in Korea but also around the world. For Koreans, education cannot be detached from considerations of social status and wealth, and that may in turn be why education oppresses people. Those were things that were very interesting to me. I want to explore the role education plays for Koreans in ‘American Hagwon.’”

Lee also stated, “I didn’t intend to become a writer from the get-go, but while dealing with health issues while working as a lawyer following law school, I started writing fiction, thinking I wanted to do something meaningful before it was too late.”

“While there were Korean American authors before me, such as Younghill Kang and Theresa Hak-kyung Cha, it was considered very strange and unusual for Korean American women to write fiction as late as the 1990s. Since then, the number of Korean American writers has increased, but I still think there isn’t enough interest and support for them. As the international popularity of the Korean wave, including Korean film and music, helps Korean American authors like me, I want to thank the Korean government and Korean artists.”

By Choi Jae-bong, literature correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 3Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 4[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 5[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 6[Special report- Part III] Curses, verbal abuse, and impossible quotas

- 7Flying “new right” flag, Korea’s Yoon Suk-yeol charges toward ideological rule

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 10Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US