hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

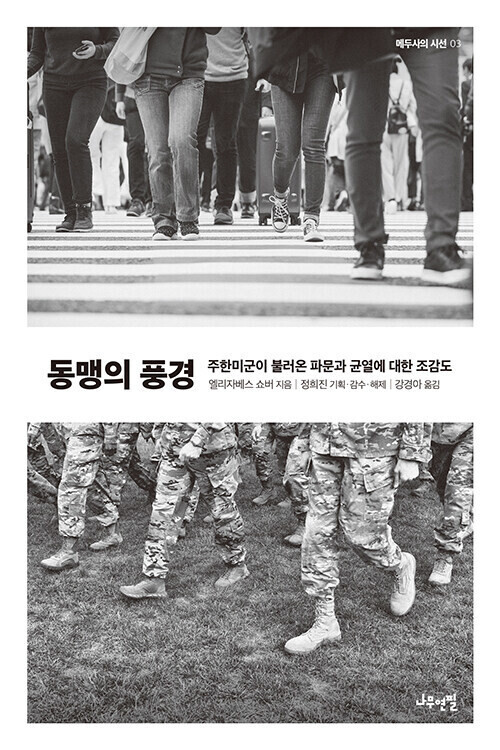

[Book review] Why Koreans turned on American troops

It’s widely acknowledged that South Korea and the US have maintained one of the strongest alliances in world history over the past seven decades.

But American troops in Korea have tended to evoke conflicting emotions for Koreans, who have viewed them both as allies and aggressors.

“Base Encounters: The US Armed Forces in South Korea,” by Elizabeth Schober, a professor of social anthropology at the University of Oslo, examines the scandals and spectacles produced by the friction between US Forces Korea (USFK) and the Korean public.

(The Korean edition of the book, titled “The Landscape of Alliance,” was translated by Kang Gyeong-ah and published by Wood Pencil Books.)

Schober met with American soldiers, sex workers in camptowns and Koreans in Itaewon and Hongdae while doing fieldwork in Korea since 2007. Her research was sparked by her curiosity about how anti-American sentiment had appeared so abruptly in Korea, given its unusually strong support for the US.

Schober’s conclusion is that the hostility that developed was driven by the issues of nationalism and gender.

The 1992 murder of Yun Geum-i, a sex worker in a “camptown” nearby US military base, was the critical moment when US soldiers were redefined as aggressors.

According to Schober, global nationalist narratives are quick to equate “national territory” with “women’s bodies.”

Schober’s most striking analysis concerns the “spaces” in which American soldiers and Koreans have interacted since the 2000s. She contends that a sense of “communitas” — how routines are rearranged and unexpected camaraderie occurs in transient spaces — took shape in the Itaewon and Hongdae neighborhoods of Seoul.

She describes this as “Itaewon suspense” because Seoul’s Yongsan District (home of Itaewon) is where men frequently engage in turf wars and argue over potential sex partners. Following the influx of US troops in the early 2000s, Hongdae was rife with scandals that gave rise to the derogatory term “Hongdae Yankee princess” (yanggongju).

But there were also anarchist and anti-military leftist punks in Hongdae who joined a campaign against the expansion of a military base in Daechu Village. Those leftist punks, Schober argues, deviated from the ideological path previously taken by folk activists.

Some readers may take issue with the author’s overgeneralization of anti-American sentiment among Koreans or her use of the concept of the “violent imaginary” in her analysis of crimes by American soldiers.

“Violent imaginary” refers to the practice of reframing violence against individuals as a national issue. Her main point is not how we distinguish the real from the imaginary, but rather the tendency to ignore stories that don’t involve violence and exploitation. That includes the voice of non-Korean women working in camptowns.

This book will likely be a bitter pill for members of the nationalist left who have found various reasons to keep gender issues out of the USFK debate for all these years.

By Lee Yu-jin, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own? [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0513/5917155871573919.jpg) [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

[Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?![[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0512/3017154788490114.jpg) [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks- [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

Most viewed articles

- 1Ado over Line stokes anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea, discontent among Naver employees

- 2[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- 3Korean opposition decries Line affair as price of Yoon’s ‘degrading’ diplomacy toward Japan

- 4US has always pulled troops from Korea unilaterally — is Yoon prepared for it to happen again?

- 5Korean auto industry on edge after US hints at ban on Chinese tech in connected cars

- 6[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- 7[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- 8[Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- 9[Photo] Korean students protest US complicity in Israel’s war outside US Embassy

- 101 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds