hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Seoul travels] Escaping the corona blues at the old site of Gyeonghui Palace

It’s a depressing season. As someone who once delivered lectures throughout the week, I’ve also seen the rhythm of my life change dramatically. Being stuck indoors day after day makes us vulnerable to catching a bad case of woe-is-me.

One good option at such times is hopping into a time machine and traveling far beyond our temporal and spatial boundaries. Travelogues from long ago offer a much-needed form of escape, if only for a moment, from our current time and place.

While rereading “Seo Yu Gyeon Mun” (Observations on a Journey to the West) by Yu Gil-jun, my eyes pause on Yu’s account of riding a streetcar in Berlin, Germany. “There are streetcars operating downtown. A streetcar is a vehicle that runs on a steel track through the power of electricity, without borrowing the strength of a machine or being drawn by horses.”

I suddenly feel the urge to go see a streetcar, a vague part of my childhood memories. Maybe that will help me shake off this mental funk.

I quickly make my way to the Seoul Museum of History. The museum is currently hosting a special exhibition about the streetcars of Seoul.

Beside the street, in front of the museum, is the statue of a woman beckoning to her son, who has forgotten his lunch box — and next to that, a streetcar that says “No. 381.” I’m told this was an actual streetcar that plied the streets of Seoul from the 1930s until November 1968.

I belong to nearly the last generation that actually experienced streetcars. My mother accompanied me aboard a streetcar several times on my way to Midong Elementary School, on Chungjeong Street. Perhaps No. 381 was the very streetcar I rode back then.

I enter the museum, which is nearly empty because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

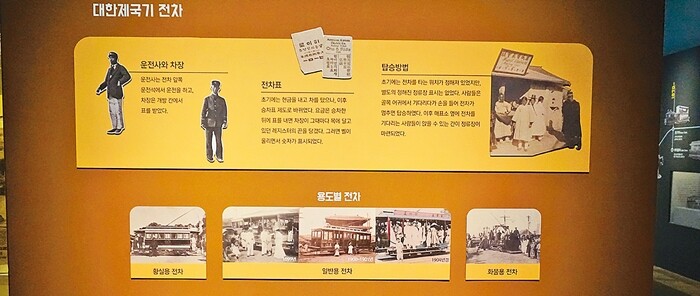

Seoul’s first streetcar entered service in 1899. The exhibition offers black-and-white photographs of people who thronged to Heunginjimun Gate (better known as Dongdaemun) upon hearing about the new machines and of eight streetcars lined up in a row. The photographs remind me of washed out landscapes.

The streetcars signified the beginning of Korea’s modernization. While looking through the exhibition, I stumble upon an interesting sentence. “Women are allowed to ride the streetcars alongside men.”

From today’s perspective, the sentence is inexplicable, but at the time, it must have been a groundbreaking advertising slogan. It would have been strange indeed for people who’d lived so long in a society that erected sharp barriers between the sexes.

Launching the streetcars not only brought freedom of movement but also initiated the regulation of time. People accustomed to the easygoing ways of agricultural society were suddenly forced to learn the chronological routine of city dwellers.

That was inevitably accompanied by the competition and stress faced by us modernites. The sense of time perceived by office workers in Seoul today only goes back 120 years.

The fiction writer Yeom Sang-seop (1897-1963) was a flaneur of Seoul. Just as the 19th century urban explorers Balzac and Baudelaire went on leisurely walks through Paris to peer into the seamier side of France’s industrialization, and just as the fiction writer Kafu Nagai (1879-1959) strolled through the back streets of Tokyo while Japan was undergoing rapid changes in the 1910s, Yeom observed how Seoul was being transformed by the streetcar.

Here’s what Yeom wrote in his piece “The Beginning,” published in 1923: “The product fairs enriched the Seoul Electric Company, bringing the sound of the streetcars nearly all the way to Bukchon. That caused the statues of the haetae [a mythical beast] to disappear almost overnight.”

But speed is a relative thing. As Seoul expanded, the plodding pace of the streetcars actually became a nuisance. The streetcar service was eventually shut down in 1968, exactly 70 years after it started.

The cafeteria on the first floor is a good place to have a cup of coffee. But I need some fresh air, so I step out into the museum’s large garden.

On a fine spring day, this would be a good place to munch on a sandwich or eat a sack lunch. Two cats that have apparently made a home in the garden were dozing in a sunny spot. Unlike the outside world, time seems to move slowly here.

I continue walking until I reach a path shaded by the trees and the old site of Gyeonghui Palace. Gyeongbok Palace was at the center of the network of palaces during the Joseon Dynasty, with Changdeok Palace and Changgyeong Palace on the east and Gyeonghui Palace on the west. The royal bedchamber in Gyeonghui Palace was known as Yungbok Hall, which is where the kings Sukjong and Yeongjo are said to have died.

Since the palaces were dismantled during the Japanese colonial occupation and only restored recently, they don’t have much of an antiquated atmosphere.

A sign at the entrance reads as follows: “This was originally the site of Gyeonghui Palace, and Seoul Middle and High Schools were established here in 1946. Until those schools were relocated to the Seocho neighborhood in 1980, many talented students were educated here, making it the cradle of Seoul’s high school population.”

That’s right. This was the location of Seoul High School, the famed institution of learning that has produced many of Korea’s best and brightest. That school was relocated after Gangnam was developed, and this area was given back to the palace.

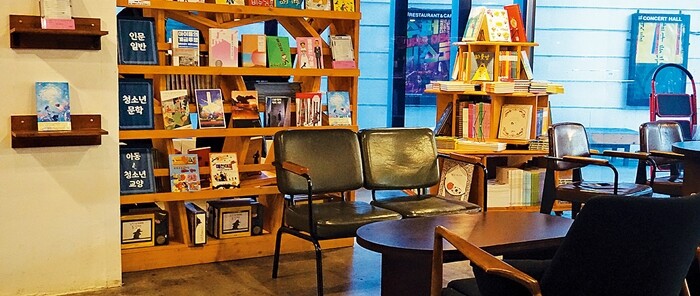

I head behind the palace toward the Asan Institute for Policy Studies and then step inside the building next door, known by the peculiar name of “Emu.” This is a multipurpose cultural space that includes a movie theater, concert hall, art museum, and book cafe.

Despite being at the end of an alley, there are a surprising number of customers here. A sign at the cafe makes a striking claim: “The cafe at Emu is located on the old site of Hoesang Hall, where kings and queens used to make love.”

Hoesang Hall was the name of the queen’s bedchambers at Gyeonghui Palace, where future kings Sukjong and Gyeongjong were said to have been born.

Turning around, I walk down Gyeonghui Palace Street No. 1 toward the entrance to the Seoul Museum of History. Along the way, I encounter an odd-looking building, which turns out to be the Czech embassy. It’s located next to the Sejong Street Local Government Building.

Old alleys have two charms: the diversity that comes from not being standardized, and their leisurely aesthetic. Past, present and future coexist on Gyeonghui Palace Street No. 1 and on Gyeonghui Palace Street, which runs next to it.

Establishments such as Sungkok Art Museum and Cafe N:Tee occupy the former homes of wealthy people, including chaebol chairmen. I doubt that their former residents ever imagined how their homes would one day be transformed.

That reminds me of a passage by Kafu Nagai, the flaneur of Tokyo’s alleys that I mentioned earlier.

“When I reflect that the temple gate by which I passed today and the large tree that gave me shade yesterday are bound to become a house or a factory, I find that even buildings with no long pedigree and trees that are not so old somehow evoke feelings of sublimity and loneliness when I gaze upon them.”

I come once again to the entrance of the museum. Past people waiting for taxis, I can see Cinecube, the indie movie theater. In front of the building, Jonathan Borofsky’s piece “Hammering Man” is still hammering vigorously, even today.

And so it is. We need to take a deep breath as we overcome the adversity of today. Merely enduring that adversity is not enough. This should be a time to train and to prepare as fiercely as that hammering man. That’s what we must do, because a season of warmth will come to us again.

By Son Kwan-seung, travel writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 2Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 3[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 4Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 5S. Korean first lady likely to face questioning by prosecutors over Dior handbag scandal

- 6[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 7Lee Jung-jae of “Squid Game” named on A100 list of most influential Asian Pacific leaders

- 8[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 960% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 10After 2 years in office, Yoon’s promises of fairness, common sense ring hollow