hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Seoul travels] Brunch in Samcheong and the taste of freedom

I go out for brunch, something I haven’t done in quite a while. In fact, a weekend brunch is one of the things we’ve lost in the pandemonium of the pandemic.

After grinding through another exhausting workweek, I like to get up late, make my way to a cafe redolent with the wonderful aroma of coffee, have a leisurely meal that doubles as breakfast and lunch, and stroll through streets and parks filled with birdsong. It’s one of the pleasures offered by the metropolis of Seoul. If there’s an appealing art exhibition on offer at a museum nearby, all the better.

But for far too long now, the abnormal has become part of our normal routines. The rigors of social distancing have imposed a sense of extreme privation in our everyday lives. Just as an empty stomach is hard to bear, so too is deprivation of spirit and culture.

The word “brunch” debuted on the global stage in 1895, in a column that British writer Guy Beringer submitted to a weekly newspaper. The next year, the word was added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

In the early 20th century, journalists in New York had a habit of eating a late breakfast on weekdays. As their habit gradually spread, brunch came to symbolize New Yorkers.

Continental Europeans owe the culinary habit of brunch to Edward VIII of Great Britain (1894-1972), one of the great romantics of his age. Edward famously abdicated the British throne so that he could marry Wallis Simpson, an American divorcee. Following his abdication, he was known as the Duke of Windsor.

Beset by reporters in the UK, Edward fled to the castle of Enzesfeld, in the vicinity of Vienna, capital of Austria. Edward frequently went golfing at the castle, which was owned by Eugene de Rothschild, of the famous Rothschild family.

Two aspects of Edward’s behavior during these outings reportedly came as a shock to staid aristocratic society. First, he wore unusual and unconventional attire to formal events. Second, he disregarded custom in his dining habits.

After partying into the early morning hours, Edward would rise late in the morning and consume a hearty breakfast, occasionally causing him to skip lunch. Just like his curious fashion sense, the duke’s peculiar eating habits were soon the talk of the upper echelons of Austria and Germany. Eugene de Rothschild once remarked that Edward was the inventor of brunch on the continent of Europe.

For the man who gladly gave up the throne of Great Britain, brunch symbolized a lifestyle that was all his own, untrammeled by traditions, norms, or restrictions.

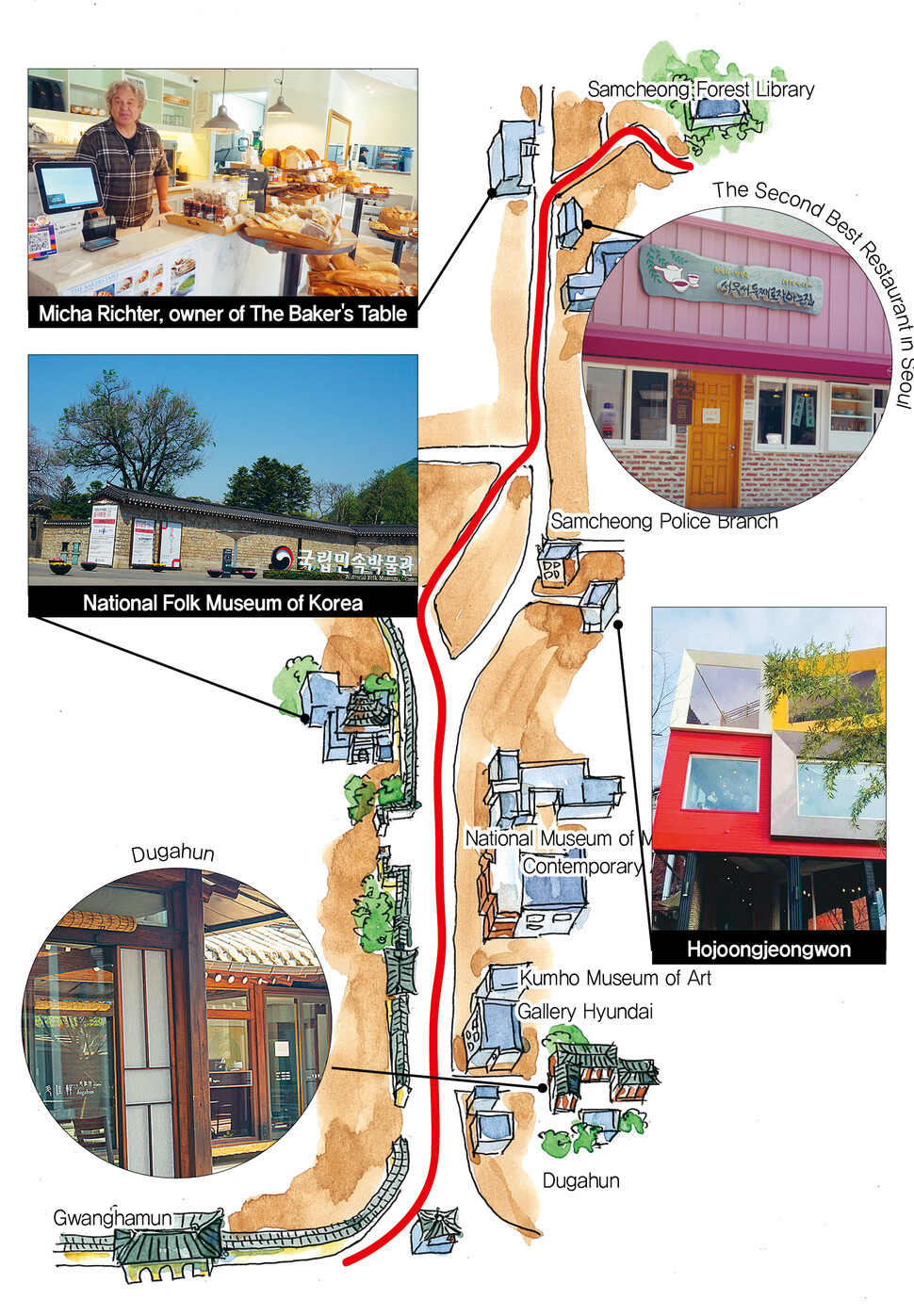

In the same way, the word “brunch” symbolizes freedom from the routine. As I strap on my mask and set out for Seoul’s Samcheong neighborhood, I’m hoping for a taste of that freedom, something I’ve missed for far too long. The Samcheong neighborhood is a place where one can count on finding brunch, strolls, and museums — the three things that feed an urbanite’s body and spirit.

The map says it’s 1.6 kilometers from Gyeongbok Palace Intersection to the entrance to Samcheong Park, which ought to take about 25 minutes by foot. But the kind of urban stroll I have in mind involves poking my nose into every nook and cranny, getting a bite to eat here and a cup of tea there. So I budget two hours.

While there are a lot of quaint alleys in the Samcheong neighborhood, I intend to walk down the main artery of traffic here, along Samcheong Street. Many streets in Seoul have narrow sidewalks where passengers must watch out for errant bicycles and motorcycles. But Samcheong Street has broad sidewalks that are great for walking. The street is typically bustling with foreign tourists, but today, it’s quiet, compliments of the pandemic.

Gazing from Gyeongbok Palace toward the Samcheong neighborhood, my eye is drawn to the stone wall of the ancient palace on the right and to a row of art museums on the left. As always, I opt for the right. Next to the Korean Publishers Association is the Kumho Museum of Art and Gallery Hyundai. Passing the Embassy of Finland, I finally reach the Seoul branch of the National Museum of Contemporary Art.

Along with the National Folk Museum of Korea across the street, the National Museum of Contemporary Art serves as a neighborhood landmark. Whenever I travel to another city, whether for business or pleasure, I try to visit a modern art museum whenever possible. I find fresh energy and insight in these museums, where art pulses like blood in the arteries of a young person in their physical prime.

Behind Gallery Hyundai is a restaurant called Dugahun that serves wine in the classy atmosphere of a hanok, a traditional Korean building. Dugahun is worth a look just for the architecture, even if you don’t actually eat there.

Hojoongjeongwon, located next to the Samcheong Police Substation, is another striking building, consisting of four cubes in different colors. This restaurant is best known for its afternoon tea set, but since it opens for business at 11 am, it’s also a good place to have brunch.

I suppress a momentary urge to follow the adjoining alley to the picturesque Bukchon neighborhood. Today, I keep walking down Samcheong Street toward the Prime Minister’s Residence. The area is chockablock with cozy cafes, galleries, and other shops whose snappy designs keep my eyes entertained.

Past the Prime Minister’s Residence are Samcheongdong Sujebi and, across the way, The Second Best Restaurant in Seoul, both renowned dining establishments. Samcheongdong Sujebi used to be a popular lunch destination for journalists and government employees. When it opened in 1976, the oddly named The Second Best Restaurant in Seoul specialized in herbal teas such as ssanghwatang, but today, it’s best known for its danpatjuk, or sweet red bean porridge.

The restaurant I’ve chosen for my brunch today is The Baker’s Table, which sells bread and serves simple meals. I like bread, and I’ve been known to drop everything and make a beeline for some good German bread.

The original location of The Baker’s Table opened near Gyeongnidan, where it helped pioneer brunch in that neighborhood. After hearing that another branch has opened in the Samcheong neighborhood, I decide to head there. The restaurant is right next to Om, an Indian and Nepalese restaurant at the junction of Samcheong Street and Bukchon Street.

The original location of The Baker’s Table has a cosmopolitan vibe because all its employees are from overseas, perhaps reflecting the large expat population in Gyeongnidan and the adjacent neighborhood of Itaewon. But here in the Samcheong neighborhood, the employees are a mixture of Koreans and non-Koreans.

I order a number of dishes, including the currywurst, a Berlin soul food consisting of a sausage slathered with curry ketchup. Since I haven’t been to The Baker’s Table for so long, I show up with high expectations — perhaps too high, since the overall quality of the food doesn’t seem to justify the price. I do notice that a lot of people are stopping by to pick up the vegetarian bread available here.

I’m lucky enough to hear the story of the restaurant directly from its owner, Micha Richter, who happens to be working here when I drop by. Born in the German city of Cologne, Micha has already been living in Seoul for more than 15 years. As a baker, he’s carrying on the family business, following in the footsteps of his grandfather and father, and he proudly shows me his “master baker” certificate.

Germans’ professionalism is one of their national strengths. I get a boost of energy from meeting people who are proud of and passionate about what they do.

The Samcheong neighborhood is turning into a place where the traditional meets the exotic. Perhaps it’s the rich aroma of the bread, or perhaps it’s because I’ve dared to go out, despite the continuing pandemic, after such a long hiatus.

My brunch was the epitome of freedom. What a wonderful day this has been!

By Son Kwan-seung, travel writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Edited by Seoul&

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 3The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 4[Column] Can we finally put to bed the theory that Sewol ferry crashed into a submarine?

- 5S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 6[Editorial] Yoon cries wolf of political attacks amid criticism over Tokyo summit

- 7Doubts remain over whether Yoon will get his money out of trip to Japan

- 8[Photo] “Comfort woman” survivor calls on president to fulfill promises

- 9[Editorial] Was justice served in acquittal of Samsung’s Lee Jae-yong?

- 101 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows