hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

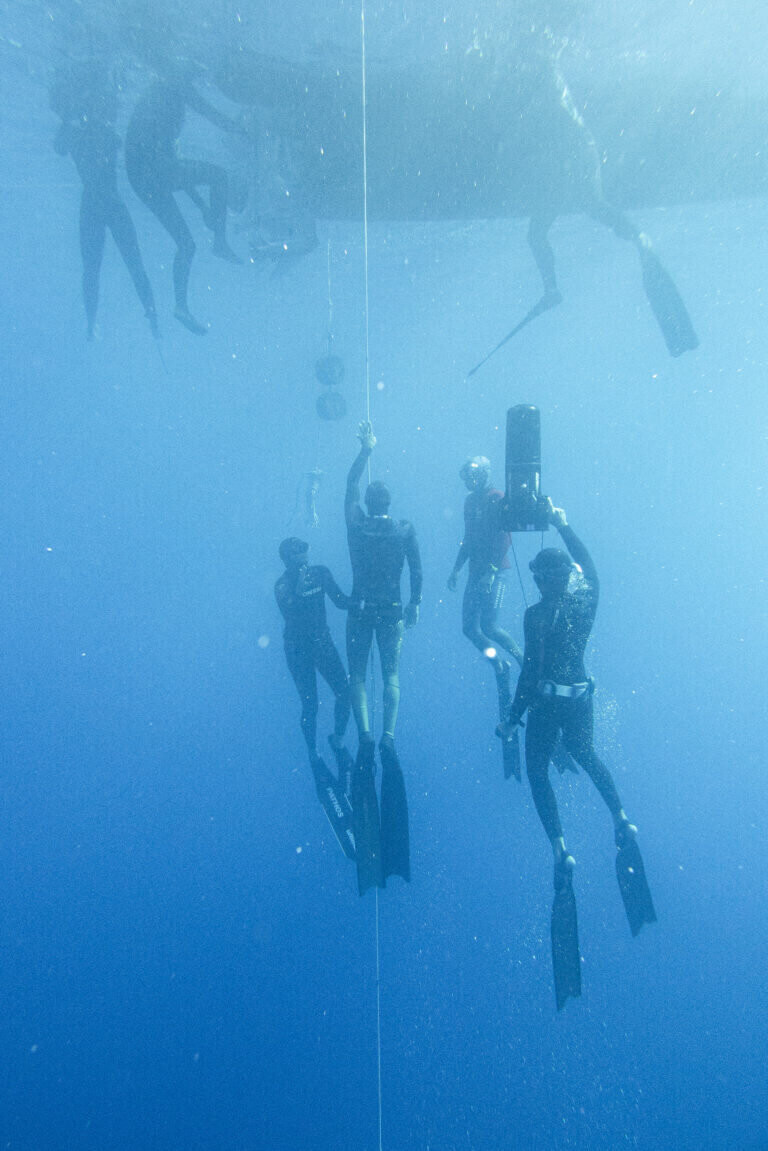

In deep water, free divers’ heart rates fall as low as seals’, international research team reveals

Seals and whales are air breathers that have adapted to aquatic life through a long process of evolution. But free divers, who don’t use a breathing apparatus, can train themselves to dive for long periods, pushing their physiological limits.

When scientists used the latest spectroscopic equipment to measure ocean dives by professional free divers, they found that oxygen levels in their brains were low enough to make ordinary people lose consciousness and that their heart rate fell to the level of a seal.

An international research team led by Chris McKnight, a sea mammal researcher at the University of St. Andrews, in Scotland, measured how heart rate, blood volume, and brain oxygenation changed during 17 deep-water dives by five elite free divers.

As soon as the divers took a deep breath and jumped into cold water, their heart rate fell from 120 to 60 beats a minute. That’s the diving response shown by all vertebrates — you can experience it yourself by dunking your face into a sink full of cold water and letting water fill your nostrils.

When breathing is impossible, the body seeks to slow the heart rate, which conserves oxygen, and to shunt blood to the essential organs, such as the heart and the brain.

When the free divers in the study reached 58 meters below the surface after a minute underwater, their heart rate dropped to 36 beats a minute. That’s the depth at which the body begins to sink as water pressure contracts air in the lungs, making the body less buoyant.

After 1 minute and 54 seconds, the free divers finally reached the bottom, at 107 meters below the surface. Their heart rate fell to 30 beats a minute.

While blood oxygenation remained at the initial level of 99%, brain oxygenation decreased from 70% to 64%. In another diving experiment, divers’ heart rare fell as low as 11 beats a minute — or a beat every 5.4 seconds.

When the free divers put on their flippers to return to the surface, their heart rate rose to 60 beats a minute, but oxygen levels continued to dip, to 95% in the blood and 63% in the brain.

At 30m below water, four minutes into the dive, professional divers were dispatched to ensure that none of the free divers ran out of oxygen and had a potentially fatal blackout.

When the divers finally reached the surface after 4 minutes and 36 seconds underwater, they showed blood oxygenation of 53% and brain oxygenation of just 26%.

“We measured heart rates as low as 11 beats per minute and blood oxygenation levels, which are normally 98% oxygenated, drop to 25%, which is far beyond the point at 50% at which we expect people to lose consciousness and equivalent to some of the lowest values measured at the top of Mount Everest,” said McKnight, the lead researcher on the project, in a statement published by the University of St. Andrew.

The researchers said these measurements were made possible by sensors attached to the forehead and waist that use near-infrared spectroscopy. These sensors work like a smartwatch, the university explained, “using light emitting LEDs in contact with the skin to measure heart rate, blood volume, and oxygen levels in the brain.”

“Before now, understanding the effects on these exceptional divers’ brains and cardiovascular systems during such deep dives, and just how far these humans push their bodies, was not possible,” said Erika Schagatay, a professor at Mid Sweden University and leader of the research project.

The researchers expect their findings will help “scientists understand the physiology of marine mammals and could help find new ways to treat human cardiac patients as well as increase the safety of free divers.”

The paper was published in the latest issue of the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, a scientific journal.

By Cho Hong-sup, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 2AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 3Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 4Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 5Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 6South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 91 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 10[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel