hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative debt-trap diplomacy?

A new form of debt risk is emerging out of China, with potential ramifications incomparably larger than those associated with the liabilities of the Evergrande Group, a Chinese real estate developer that is already terrifying global financial markets.

The new risk lies in the massive debt amassed by developing countries in Asia and Africa, where China has been pursuing social infrastructure projects over the past two decades. Analysts fear that much of this debt is a ticking time bomb, which stands to trigger a severe crisis for developing countries already struggling with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

AidData, an international development research team affiliated with the College of William and Mary, recently published a report analyzing 13,427 of China’s overseas assistance projects pursued through this year, with approval dates between 2000 and 2017.

In 2013, China officially declared its Belt and Road Initiative, with the aim of creating an economic sphere spanning Asia, Europe, and Africa by means of a “21st-century Silk Road.” But it had also been involved in many development projects in developing economies before that.

The report estimated the scale of China’s projects over the 18-year period at US$843 billion across 165 countries, adding that another US$385 billion in previously undisclosed “hidden debts” had been identified.

According to the report, debts to China amounted to 10% of gross domestic product for around 40 middle- to low-income countries, with 60% of that consisting of previously undisclosed debt.

“It really took my breath away when we first discovered that [$385 billion in debt],” said Brad Parks, executive director of the AidData team, to the Financial Times.

“These debts for the most part do not appear on government balance sheets in developing countries,” he added.

“The key thing is that most of them benefit from explicit or implicit forms of host government liability protection. That is basically blurring the distinction between private and public debt.”

This means that even if the funds were nominally borrowed from the Chinese government or financial institutions by non-government sectors, they ultimately pose risks to the government — and the amounts involved have not been disclosed in a transparent manner.

As a prime example of hidden debt, the report singled out a high-speed rail project between the Chinese city of Kunming and the Laotian capital of Vientiane.

The project cost US$5.9 billion, or roughly one-third of Laos’ yearly GDP. Sixty percent of that — amounting to US$3.5 billion — consisted of loans from the Export-Import Bank of China to the project’s operator, the Laos-China Railway Co.

A condition of this arrangement was that the Laotian government would foot the bill if the company failed to turn a profit. The Laotian government also invested in the project with its own US$480 million loan from the Export-Import Bank of China.

Seventy percent of the Laos-China Railway is owned by three state-run Chinese companies, which have structured their corporations so that they do not assume responsibility for defaults on debts.

The company began operating this year, and the Laotian government is optimistic that it may start performing in the black by the sixth year of the project, in 2027. But the AidData report noted that projections for its main source of revenues — freight and passenger service between China and Thailand — were uncertain.

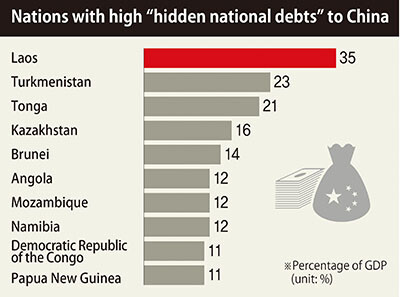

In Laos’ case, this sort of hidden debt amounts to 35% of GDP. Other countries with large hidden debt burdens include Turkmenistan (23%), Tonga (21%), Kazakhstan (16%), Brunei (14%), Angola (12%), Mozambique (12%), Namibia (12%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (11%), and Papua New Guinea (11%).

The research team calculated an average of US$85 billion in international development funds provided by China each year since 2000 — 2.3 times the annual average of US$37 billion provided by the US.

Only around 3% of this total is pure aid; most of the remainder consists of loans by financial institutions. This suggests that the Belt and Road Initiative and other overseas efforts by China are less about providing support to developing countries than about doling out commercial loans.

According to the report, China’s expansion of its Belt and Road Initiative has led to an increasing percentage of funds being provided by state-owned commercial banks, resulting in a larger collateral burden for developing countries.

In many cases, Chinese banks use contracts for future exports of raw materials as collateral for developing countries in order to reduce the risk that they will be unable to recover their funds, with relatively high interest rates in the range of 6%, the report said.

Countries identified as having a particularly high rate of secured loans among their total funds from loans included Venezuela (92.5%), Peru (90.0%), Turkmenistan (88.6%), Equatorial Guinea (80.3%), and Russia (76.6%).

In its earlier overseas efforts, China chiefly provided funds to government institutions. Since then, its approach has increasingly shifted toward loans to state-run businesses and the private sector.

As a result, funds provided to state-run businesses, banks, special purpose companies, joint ventures and private enterprises amount to 70% of the current total. This change in the targets of loans is being cited as a factor behind the snowballing of “hidden debt” that does not appear in government statistics.

Additionally, many of the projects have been associated with serious societal issues during the implementation stages. The report noted that 35% of projects had resulted in controversy over corruption, labor standard violations, environmental damage or faced setbacks due to protests by local residents.

“Over the last two decades, China has provided record amounts of international development finance and established itself as a financier of first resort for many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs); however, its grant-giving and lending activities remain shrouded in secrecy,” the AidData report said.

The emergence of the developing countries’ hidden debt burden as an issue has prompted the US to take action. Early this month, it announced a “Connecting the Dots” plan jointly with the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, with the aim of pursuing sound infrastructure projects.

The main objectives of the plan are to root out the corruption that so often occurs with development projects in developing countries, while supporting the establishment of high-quality infrastructure.

According to the US State Department, the plan also serves as a supplement to the Blue Dot Network mechanism proposed by the US, Australia and Japan in 2019 as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

In remarks indirectly targeting China, Secretary of State Tony Blinken said, “At a time when others are driving an approach to infrastructure projects and developing economies in which overseas companies import their own labor, extract resources, fail to consult with communities, end up driving countries into debt, we’re here today because we’re championing a different approach.”

“Rather than race to the bottom, we, together with like-minded government, private sector, and civil society partners, we want to spark a race to the top for quality, sustainable infrastructure around the world,” he continued.

Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post observed that commercial financial institutions in the US and other Western countries paved the way for China to expand its project’s scope by avoiding low-development countries in Africa and elsewhere, which they see as risky investments. It interpreted the recent moves by the US as a bid to increase investment from the G7 members and other countries by certifying the projects as being in line with “sound international standards.”

In June, the G7 countries announced the Build Back Better World initiative, which involves collaborating on the US$40 trillion in investment necessary for developing countries through 2035.

Chris Alden, a professor of international relations at the London School of Economics and Political Science, saw Blinken’s announcement as being rooted in collaborative efforts to restore infrastructure sector market share in markets where China’s Belt and Road Initiative projects predominate.

Seifudein Adem, a professor of global studies at Japan’s Doshisha University, described the effort by the US as a reaction to China’s policies and activities, noting that the same idea had previously been expressed in 2016 by then-Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

For that reason, some are predicting the situation could develop into a battle for Africa and other countries between the US and China.

But others are noting the potential for the US and China to pursue projects without fixating on zero-sum competition.

David Shinn, a professor of international relations at George Washington University, said the plans of the G7 and China “are different initiatives, and one does not preclude the other.”

“The more distance that can be put between B3W and [the Belt and Road Initiative], the better,” he suggested.

By Shin Gi-sub, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 6The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 9Ferry accident likely due to whale; 1 killed

- 10[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?