hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Japan mulls another site of forced Korean labor for UNESCO designation

The Japanese government is reportedly in a deep quandary ahead of its application to designate a gold mine site, at which large numbers of Koreans were forced to perform labor against their will, as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

That’s because it has already received a warning from UNESCO over the failure to honor the promise it made when it registered the island of Hashima, also known as Gunkanjima or Battleship Island, in 2015. At the time, it pledged to relate “the entire history” connected with the site, including the forced mobilization of Koreans.

This means that if another controversy were to erupt as South Korea or other parties raise issues, Japan would find itself very much on the defensive.

On Dec. 28, a Japanese cultural review panel selected the Sado gold mine site in Niigata Prefecture as a candidate for UNESCO World Heritage site registration. If the Japanese government wants a registration review to take place in 2023, it will need to submit an official recommendation to UNESCO by Feb. 1.

The actual decisions on whether to register sites are based on reviews and recommendations by the International Council on Monuments and Sites, a UNESCO advisory body.

“It’s a lot for us to consider,” a Japanese government official recently told the Asahi Shimbun newspaper, adding that the Sado mine site’s nomination “would inevitably lead to an outcry from South Korea and create new potential for conflict between South Korea and Japan.”

The threat to relations with Seoul is not the only factor making things awkward for Tokyo. It is also facing scrutiny from the international committee over the failure to honor the promises it made while registering Hashima Island in 2015.

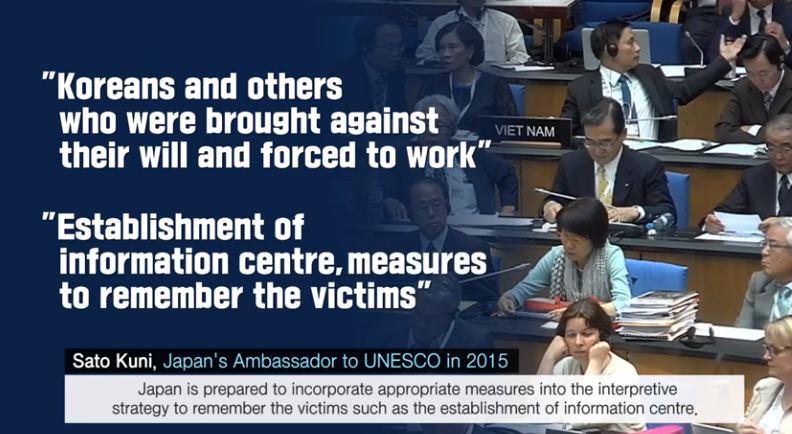

When Hashima and 22 other “Sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution” were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in July 2015, the Japanese government acknowledged that “many Koreans and people of other nationalities were mobilized against their will and forced to labor under harsh conditions during the 1940s.” It also promised to “take measures including the establishment of information centers to remember the victims.”

But when the Industrial Heritage Information Centre was opened in Tokyo’s Shinjuku area in June 2021, it was revealed to be filled with historical inaccuracies, including claims that there had been “no discrimination against Koreans.”

After conducting an on-site examination, UNESCO adopted a resolution in July 2021 urging Japan to faithfully comply with its promise to memorialize “the entire history.” The South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs was also critical of the center, with a spokesperson issuing a statement on Dec. 28 calling on Japan to “fully implement the relevant decisions of the [World Heritage Committee].”

The Japanese government now has to submit an implementation report on the matter by Dec. 1 of this year. That report will serve as a basis as the World Heritage Committee conducts another review at its 46th meeting, which is scheduled to take place in 2023.

Much like Battleship Island before it, the Sado mine site is also poised to be a source of controversy over historical inaccuracies if it undergoes a UNESCO review.

According to a report by Japan’s NHK network, a Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs official attending a closed-door cultural review panel meeting in November 2021 warned that South Korea was “already watching the Sado [mine] matter with a heightened sense of alarm.”

The same official also said that conflict would “be unavoidable even if the scope is narrowed to the Edo era [not including the period of occupation].”

Historical materials unambiguously document the forced mobilization of some 1,200 Koreans to work at the Sado mine site beginning in February 1939.

The Japanese government also stands to suffer a political blow if it opts not to submit the recommendation for fear of international condemnation.

The Sado mine site was initially included on a provisional UNESCO World Heritage site list in 2010, only to end up being omitted after four rounds of competition starting in 2015. Niigata Prefecture and the city of Sado only narrowly made the candidate cut this time around.

The Asahi Shimbun reported that whether or not the site is approved could have political ramifications at a local level, referring to the Niigata gubernatorial election in May and the Upper House election this summer.

Meanwhile, the question of the Sato mine site’s safety is emerging as a focus of attention in Japan.

A framework plan for historical site servicing drafted by the city of Sado in March 2020 noted that servicing was being planned for over 30 locations due to collapse and other forms of damage. Among them was Doyu no Wareto, a V-shaped peak that has become a symbol of the Sado gold mines.

Doyu no Wareto has already begun partially collapsing, with additional collapse prevention measures needed along its slope to preserve it in its current condition.

By Kim So-youn, Tokyo correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 3Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 4[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 5For survivor, Jeju April 3 massacre is a living reality, not dead history

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 8[Special Feature Series: April 3 Jeju Uprising, Part III] US culpability for the bloodshed on Jeju I

- 9[Column] America must frankly own up to role in tragic Jeju April 3 Incident

- 10‘My mission is suppression’: Jeju blood on the hands of the US military government