hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

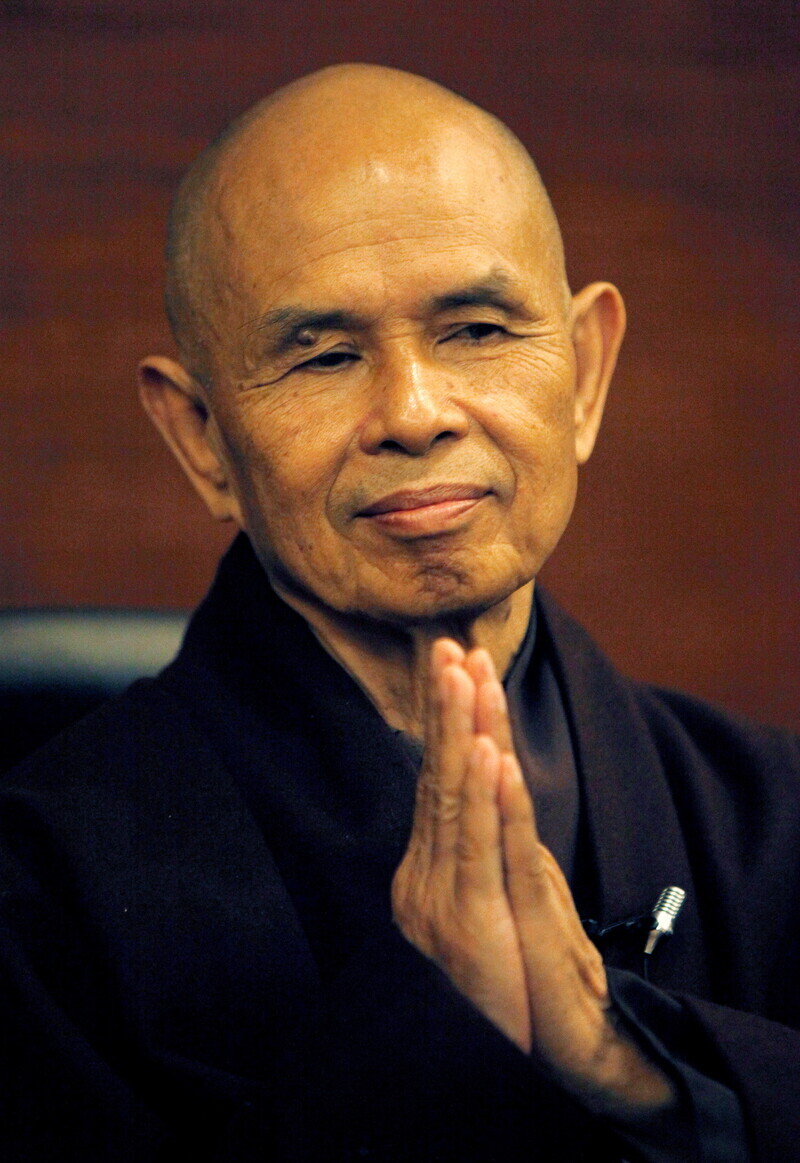

Remembering “living Buddha” Thich Nhat Hanh, advocate for peace in trying times

Thich Nhat Hanh, renowned around the world for his meditative practice and his work as a peace activist, passed away on Friday at Tu Hieu Pagoda in Hue, Vietnam. After 79 years as a monk, he died at the age of 95.

A native of Vietnam, Thich Nhat Hanh was regarded as a “living Buddha” and a “spiritual teacher” along with the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibet.

Born in a rural village in central Vietnam on Oct. 11, 1926, Thich Nhat Hanh decided to enter monastic life in 1942 at the age of 16, determined to become as peaceful as a monk he’d seen in a photograph.

But not even Buddhist temples were a refuge from war-torn Vietnam’s struggles against foreign powers. As the French military fought to maintain control of Vietnam from 1946 through 1954, it attacked temples and executed monks for taking part in the resistance movement.

Thich Nhat Hanh didn’t allow hatred to overcome him, however. Following the teachings of the Buddha, he accepted French soldiers as his friends and brothers.

During a lecture tour in the US in the 1960s, he condemned the tragedy of the Vietnam War and called for peace. He also led a Buddhist delegation to the Paris peace talks where he pushed to end the war.

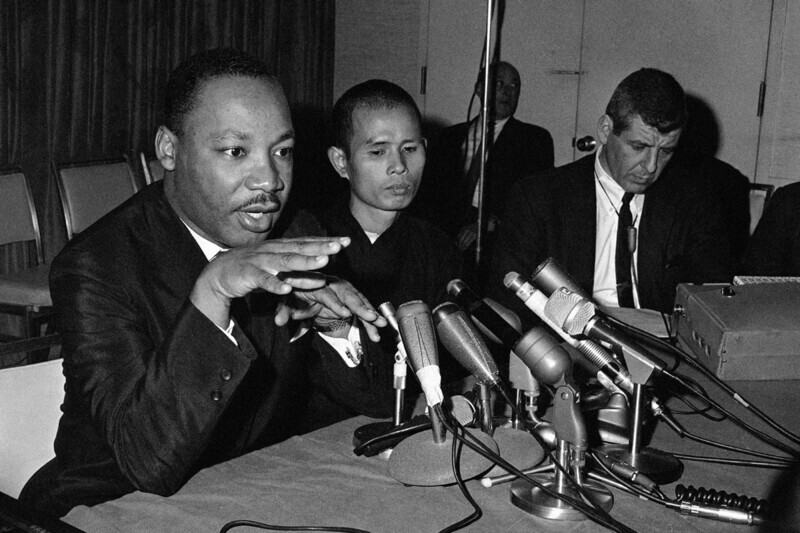

Through the work of Thich Nhat Hanh, the concept of “engaged Buddhism” began to spread around the world. He met with civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr., and asked him to actively support the resolution of conflicts. That inspired King to nominate Thich Nhat Hanh for the Nobel Peace Prize.

But the North and South Vietnamese governments banned Thich Nhat Hanh from returning home because of his remarks about peace. In 1973, he sought asylum in France, where he established the Plum Village community in a rural village to support war orphans in his homeland. He led meditation programs that focused on walks and mindfulness that created a sensation in European society. He also set up the Green Mountain Dharma Center in the US in 1990, which left a strong impression on those who were fed up with the materialism of the West.

Thich Nhat Hanh’s compassion for the suffering was in strict accordance with Buddhist teachings, not merely a political stance. After the US invaded Iraq under US President George W. Bush, Thich Nhat Hanh warned Bush that he would suffer as much pain as he inflicted. Following the 9/11 terrorist attacks in 2001, he organized a 10-day fast to comfort the victims and their families.

“In my practice, I seek to open my eyes to suffering and to comprehend its causes, rather than avoiding it. Suffering helps us to gain understanding and compassion for others, and our understanding and compassion can bring us peace,” he taught.

The monk had staff hang up pictures of Buddha and Jesus at Plum Village.

“We don’t ask Westerners to give up their religion, but to study Buddhism. By understanding Buddhism, you can gain a deeper understanding of Christianity. If you then delve more deeply into your religion, you will find similarities with Buddhism,” he said.

“In Plum Village we say that the Kingdom of God is now or never, and this is our practice.”

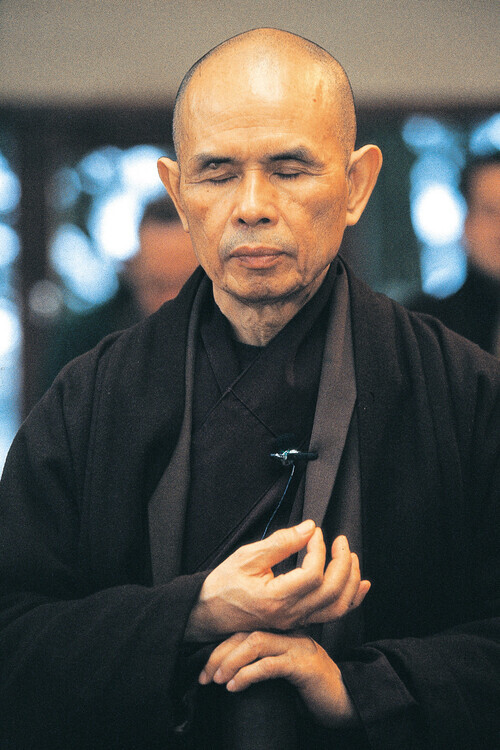

In his meditation sessions, Thich Nhat Hanh sought to gently change people. “Don't be angered by your bad habits. Don’t fight the habit, and keep a smile on your face. Doing that will lead to gradual change,” he said.

The monk didn’t push people into asceticism or meditation. “Whatever you do, don’t focus on your worries, anxiety or delusions — focus your mind on your breathing and the bottom of your feet and stay fully focused on what you’re doing right now,” he said.

“Being awake right here and right now is the Pure Land and heaven.”

Thich Nhat Hanh didn’t get much attention when he first visited Korea in the 1990s. But when he visited in March 2003, right after his book “Anger: Wisdom for Cooling the Flames” became a bestseller, there was a surge of interest in the monk and in walking meditation.

During that visit, he prayed for peace on the Korean Peninsula during a session of walking meditation at Dorasan Station in Paju, Gyeonggi Province. He also organized walking meditation for peace in Iraq and the Korean Peninsula in front of Seoul City Hall, in an event that drew more than 100,000 people.

In addition to “Anger,” books by the monk that have been published in Korea include “The Miracle of Mindfulness” and “How to Walk.” He published more than 100 books during his lifetime and is credited with conveying the teachings of the Buddha in language that’s at once concise and poetic.

Throughout his life, Thich Nhat Hanh demonstrated that the most traditional things often have the widest global appeal. Even in France, he maintained the Buddhist traditions he’d learned at Vietnamese temples, which he shared with all, regardless of their religion, race or ethnicity.

He has quite a few followers among Quaker and other non-ecclesiastical Christian communities such as Woodbrooke in England and Pendle Hill in the US, both world-class religious schools that were said to have influenced Gandhi and Ham Seok-heon. The Bruderhof, a leading association of spiritual communities within Protestantism, also reduced the number of foods in their diet and pursued a more frugal life under the monk’s influence.

Thich Nhat Hanh delighted Korean followers and fans when he was interviewed by the Hankyoreh at Plum Village, France, in July 2003. “I kept talking about Korea for a week after coming back, and haven’t felt as comfortable as I did while sleeping at Songgwangsa Temple. I must have been a Korean monk in a previous life,” he said.

Thich Nhat Hanh also shared his regret about the news of Hyundai Group Chairman Chung Mong-hun’s suicide, which he’d happened to hear about on the morning of the interview.

"If he’d talked to me beforehand, I doubt he would have jumped like that,” the monk mused. “Political leaders and businesspeople need to have people to provide spiritual help. Otherwise, how can they bring us to the hill of peace?”

Thich Nhat Hanh suffered a stroke in 2014 that left him unable to speak. He returned to Vietnam in 2018 to live out his days in the village of his birth. In his will, he asked for his body to be cremated and the ashes sprinkled over meditation trails at Plum Village communities around the world.

As news of his death spread, messages of condolence poured in from around the world. In a message shared on Twitter, the Dalai Lama called the deceased monk his “friend and spiritual brother” and said that “the best way we can pay tribute to him is to continue his work to promote peace in the world.”

President Moon Jae-in also communicated his condolences on social media, describing Thich Nhat Hanh as a “practicing Buddhist activist who demonstrated his love for humanity through his actions.”

“The monk’s footsteps, words and teachings will forever live and breathe in people’s practice,” Moon added.

Before his death, Thich Nhat Hanh authored a lullaby for the dying in which he wrote: “This body is not me; I am not caught in this body, / I am life without boundaries, / I have never been born and I have never died. / [. . .] / Birth and death are only a door through which we go in and out. / Birth and death are only a game of hide-and-seek. / So smile to me and take my hand and wave good-bye. / Tomorrow we shall meet again or even before. / We shall always be meeting again at the true source, / Always meeting again on the myriad paths of life.”

By Cho Hyun, religion correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 5[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 8Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 9Nearly 1 in 5 N. Korean defectors say they regret coming to S. Korea

- 10Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range