hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Inside the Olympics’ “closed loop” pandemic bubble

While the Games are a chance for China to show off the superiority of their system, the isolation and lack of choices have left many disgruntled

After kicking off on Feb. 4, the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics are now drawing to a close. Due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, this year’s Games are taking place within a thorough disease prevention system called the “closed loop” — one that completely separates Olympic participants and ordinary Chinese people in order to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Participants can only move back and forth between their hotel rooms and Olympic events, both enclosed within barbed-wire fences and by Beijing’s public security officers. In a sense, China has created a city within the massive city of Beijing — all for the sake of the Olympics.

So far, the closed loop is working. Particularly noteworthy, daily caseloads have dropped significantly in Beijing despite the worldwide spread of the Omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus, found to be much more transmissible than previous variants. This is a dramatic departure from Tokyo, where daily caseloads surged during the Games last summer. A brief glance at the situation seems to indicate that China has proved the efficiency of its system through this year’s Olympics as planned.

A de facto ration system where cigarettes are hard to come byThe problem is that the continued closure has led to increased predicaments among participants.

Though the Games are technically scheduled for two weeks, from Feb. 4 to Feb. 20, reporters and Olympic participants have been in China since late January. In my case, I arrived in China on Jan. 30 and have been inside the closed loop for almost two weeks. Before I arrived, I didn’t expect there to be many difficulties during my three-week stay in Beijing, and early in the Games, I was even awed by the thorough disease prevention measures in place — ones in a different league compared to the clumsy disease prevention measures of the Tokyo Olympics. But as the Games progress, I feel the heaviness of the remaining days grow. Only after losing my freedoms have I realized their importance.

From the outset, the Beijing Winter Olympics organizing committee said every aspect of life can be taken care of within the closed loop. It emphasized that there’s no need to worry about food and basic necessities, as there were convenience stores located in every hotel inside the bubble. However, hotel convenience stores have proved to be more like stalls at makeshift kiosks.

At the hotel I’m staying in, I can only access a few different types of cup noodles, snacks, beer, and drinks. That familiar Shin Ramyun and hot chicken Buldak Bokkeum Myeon were among the few cup noodles available in the store offered me a little bit of relief. In terms of basic necessities, there are detergents, toiletries, and face masks on display at the convenience store, but only a few options are available. The situation is similar at the only convenience store at the Main Media Center. Even if there’s an item you need, you can only select from items brought in by hotels and the organizing committee, making it almost feel like a rationing system is in place.

This has led to difficulties in actual life. Due to the dry weather in Beijing, my skin is drying and cracking, but the body lotion sold at my hotel hasn’t been of any help. There’s no other way to get my hands on a different lotion. Though the home button on my old iPhone is broken, I can’t get it repaired, nor can I get a new phone. Perhaps people living inside the closed loop should start bartering used items with each other. During the Tokyo Olympics, participants could go out on 15-minute convenience store runs, and now I viscerally understand how precious that allotted time was.

Eating has become important as there are no leisure activities available, but even food options are extremely limited. The fried chicken and pizza depicted on billboards I pass by on my bus rides feel like a pie in the sky — no, fried chicken in the sky. There’s even a shortage of cigarettes among Olympic participants. Though they came to Beijing expecting to have access to regular convenience stores, there’s actually nowhere to buy cigarettes inside the closed loop. Living in a space where even the most primal freedoms are restricted has made people in the closed loop joke sourly, “It feels like we’re in boot camp.”

Even Chinese people are joining in the chorus of complaints.

A volunteer who works at a stadium in downtown Beijing said, “Doing the same thing day in and day out has become tiring.” These volunteers — over 19,000 of them — have been living in confinement in the closed loop for over a month since January. Though selected from a huge applicant pool of 1 million, hoping to help in a national event, even they are complaining of hardship from their prolonged period of confinement.

There are an estimated 40,000 Olympic authorities as well as hotel employees and public security officers trapped inside the closed loop. These people even had to spend the Spring Festival, the biggest holiday in China, inside the closed loop, and may have to go through quarantine even after the Olympic Games are over.

Another controversy is how excessively pricy everything is inside the closed loop. You would expect cheaper prices considering how options are limited, but it almost feels like the situation is being taken advantage of for profiteering.

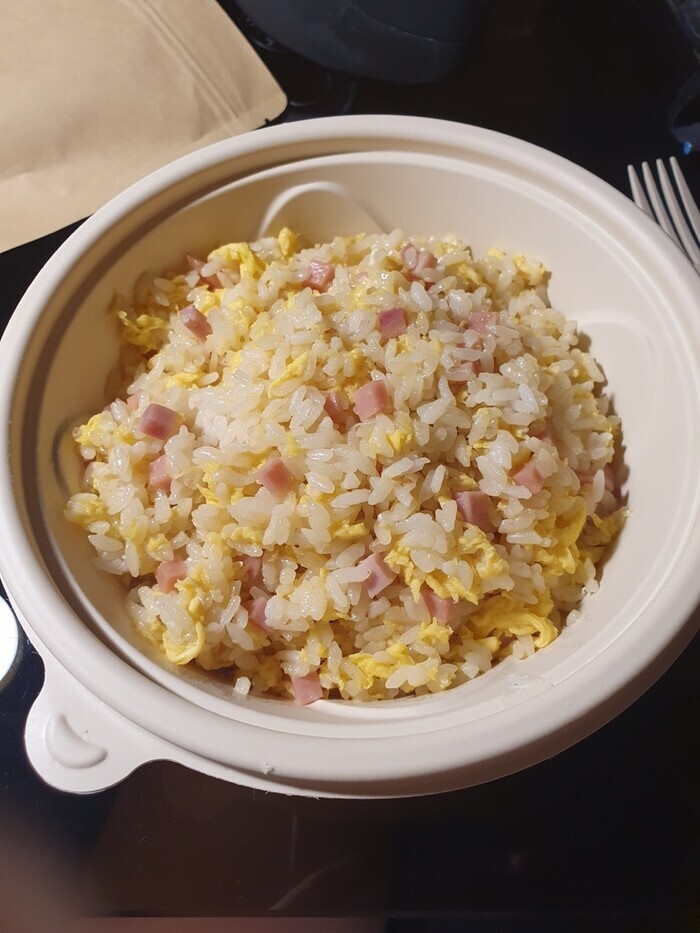

The only restaurants available to participants are the ones at the Main Media Center, stadiums, and hotels. A simple bowl of rice with toppings at the Main Media Center costs at least 55 yuan, and Chinese lunch boxes sold at stadiums cost 60 yuan. Western-style lunch boxes with meat even cost up to 120 yuan. Some hotels where reporters are staying charge 109 yuan for a ham fried rice — surely a rip-off. This is why many choose to stockpile cup noodles and snacks provided by the organizing committee.

The same can be said of transportation costs. There’s no public transportation available inside the closed loop, and the only options for transportation are buses operated by the organizing committee or private taxis. For reporters who have to go from one stadium to another quickly, taxis have proved to be overly expensive, as they’re four to five times more expensive than the regular taxi fare in Beijing. If you take a cab back to your hotel after an event late at night, you have to prepare yourself to shell out at least 80,000 to 100,000 won for a one-way charge. Even though this is all to help prevent the spread of COVID-19, the cost is shouldered by individual participants — in sharp contrast to the Tokyo Olympics, during which the organizing committee provided 10 taxi vouchers worth 10,000 yen each.

Other foreign participants of the Olympics are raising similar concerns. For example, CNN reported on Feb. 9 that the food quality at restaurants available to Olympic participants, including that at the Main Media Center, has been found to be quite low. It even cited a manager of a hotel that provides food services inside the closed loop, who admitted that the food in one of their own restaurants is “disgusting.”

German team chief Dirk Schimmelpfennig told CBS that the living conditions at the German athlete’s hotels were “unacceptable,” adding that athletes deserved to have additional food delivered from outside the closed loop.

Pressure to pull off a “zero COVID” GamesThe Beijing Winter Olympics’ enforcement of the closed loop is really an extension of the zero-COVID strategy maintained by China, which has criticized other nations’ “living with COVID” policies and continued to strictly adhere to vehement disease prevention policies. In China, a single positive COVID-19 case results in the total lockdown of the affected area, and the lockdown is lifted only when there are no more positive cases based on nucleic acid amplification tests.

In Xi’an, China, mass infection resulted in a complete lockdown of the city last December that left residents confined for over three weeks. People subsisted on expired bread and later bartered game consoles for food due to lack of basic necessities. Some residents at wit’s end ventured out of their homes only to be assaulted by quarantine agents. Though living in lockdown is a unique experience for Olympic participants, it’s something that can happen anytime to people living in China.

China is enforcing such intense disease prevention measures in order to propagandize the supremacy of the Chinese system. China emphasizes that its party- and government-centered policy of control is much more efficient than what western systems can offer. In addition, based on the success of the Beijing Olympics, Chinese President Xi Jinping will be vying for a third consecutive term in the upcoming National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in October. Though many question whether China will be able to sustain its policy direction considering the spread of the Omicron variant, a switchover from its existing disease prevention strategy would be difficult, as that would be tantamount to admitting failure.

The closed loop is not just a tool for the successful completion of the Olympics, but a microcosm of the world China hopes to build for itself. It will be interesting to see how those who return to the “free world” after the Olympics will evaluate the closed loop.

By Lee Jun-hee, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 2Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 360% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 4[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 5AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 6Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 7[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 8Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 9Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 10Gangnam murderer says he killed “because women have always ignored me”