hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Will Korean YouTuber fighting in Ukraine be first to stand trial for waging “private war”?

The South Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs will be charging former Korean Navy SEAL Ken Rhee for violating the Passport Act by entering Ukraine without government authorization. South Korean nationals are currently banned from traveling to Ukraine following the escalating crisis in the region. Additionally, Lee may be subject to punishment under criminal law due to a clause prohibiting individuals from waging “private war.”

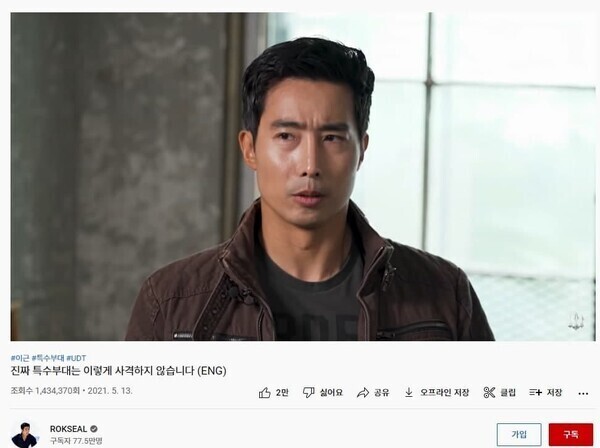

A former captain in the South Korean Navy’s Naval Special Warfare Flotilla, also known as UDT/SEAL, who became a household name through his YouTube series “Fake Men,” Rhee announced on social media that he arrived in Ukraine in order to join the volunteer foreign legion. The South Korean government confirmed Rhee’s entry into Ukraine.

Article 111 of the Criminal Act stipulates that “a person who wages a private war against a foreign country shall be punished by limited imprisonment without prison labor for at least one year.” In place ever since the Criminal Act was first established in September 1953, the charge is an unfamiliar one to many — not just now but even at the time of its legislation right after the Korean War.

There’s an interesting passage regarding the clause among what was recorded of the legislation process of the Criminal Act. On the morning of June 29, 1953, during the second reading of the Criminal Act draft, Eom Sang-seop, then-deputy head of the National Assembly’s Legislation and Judiciary Committee, read out loud the clause prohibiting private war.

According to stenographic records, one of the lawmakers present asked, “What is a private war?” Eom responded, “[It means] a personal war [. . .] It’s when an individual, out of his own will, takes up arms against a foreign country and causes problems instead of doing so at the national level or upon the command of the Republic of Korea. Through such behavior, the individual may claim to be our country’s volunteer soldier and participate in foreign wars, which can cause diplomatic problems. That’s what a private war is.”

Upon Eom’s explanation, lawmakers finally answered that they had no objection, after which then-Vice Chairman of the National Assembly Yun Chi-young approved the legislation.

According to “The Annotated Criminal Act” by Kim Dae-hwi and Kim Shin, the clause against private war is based on the constitutional provision that “the Republic of Korea shall endeavor to maintain international peace and shall renounce all wars of aggression.” The two authors explain that partaking in a private war is a punishable offense because “citizens waging private war against a foreign country at will not only contradicts the Constitution but may also threaten the existence of the Republic of Korea by worsening diplomatic ties and peaceful international relations.”

Hence, the clause against private war stipulates that individuals or private organizations who wage war against a foreign country without a presidential declaration of war in accordance with Article 73 of the Constitution and the National Assembly’s consent of such a declaration of war in accordance with Article 60, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution shall be subject to punishment. The clause does not apply to battles waged against specific regions or groups other than state powers.

The private war charge is applicable to would-be offenders as well. Premeditated preparation for private war such as the provision of weapons, munitions, or funds can be punished by imprisonment without prison labor for up to three years or a fine of up to 5 million won, or roughly US$4,000.

Since its legislation, the private war charge has never been pursued. Perhaps because of this, the Korean Bar Association in 1985 suggested that the virtually meaningless clause be abolished. The South Korean government previously considered pursuing the charge when it was determined that an 18-year-old identified with the surname Kim who had gone missing in Turkey in 2015 joined and was receiving training from the Islamic State. The case was ultimately not prosecuted, as Kim has remained missing.

By Kim Nam-il, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 3Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 4[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6Historic court ruling recognizes Korean state culpability for massacre in Vietnam

- 7Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 8Story of massacre victim’s court victory could open minds of Vietnamese to Korea, says documentarian

- 9Historic verdict on Korean culpability for Vietnam War massacres now available in English, Vietnames

- 10Bills for Itaewon crush inquiry, special counsel probe into Marine’s death pass National Assembly