hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Aboard trains full of refugees, Ukrainians check social media for signs husbands, sons are OK

White steam shot into the air as the train approached the platform at a station packed with people. The train was heading from the small town of Przemysl, on Poland’s southeastern border, for Krakow, the country’s second-largest city. Adults and children hurried around with backpacks on their shoulders and heavier suitcases trailing behind them.

Ever since the outbreak of war in Ukraine on Feb. 24, this Polish train station, the nearest to western Ukraine, has been packed with refugees. Nine out of 10 of the passengers on these trains are Ukrainians who had crossed the border, fleeing the war. In effect, the trains departing this station are carrying refugees to other countries in Europe.

Anna, a 37-year-old from Kyiv, Ukraine, was among those who boarded the train on March 10. She and her two daughters left their house behind the day the Russian military declared war on Ukraine.

Anna will never forget that morning. “It was around 7 am when I was woken by an unfamiliar sound. It sounded like a car alarm going off — that loud noise cars make when someone tries to break into them,” she said.

“I went to the window to see what the matter was. It was too dark to make anything out, and my husband told me to relax. I got back into bed, but I couldn’t get to sleep, so I checked the news on my phone.”

Though war had begun, Anna didn’t want to leave her home. But by that afternoon, she was overcome with terror at the prospect of not being able to take her children to safety. Her husband drove them 16 hours to the west and then returned to Kyiv alone, to join the fighting.

According to data from the UN Refugee Agency, 2,698,280 Ukrainian refugees had crossed the border from the beginning of the war through March 12. Two-thirds of them had entered Poland (more than 1.65 million, as of March 13), while the others were moving through Hungary (240,000) and Slovakia (190,000).

“I have worked in refugee emergencies for almost 40 years, and rarely have I seen an exodus as rapid as this one,” said Filippo Grandi, the UN high commissioner for refugees, in a statement on March 3.

The numbers alone would suggest this is more serious than the Syrian refugee crisis in 2015, when around 1 million refugees arrived in Europe, prompting a political lurch to the right.

But European countries’ reaction has been quite different this time around, perhaps because they regard the terrible war afflicting their neighbor Ukraine as being something that concerns themselves. The Polish government has granted Ukrainian refugees free passage on trains and other means of transportation, and the EU is quickly working on simple entry procedures for refugees and a way for them to go to work and put their children in school.

While the air outside was chilly, the train carriages were warm with the bustle of people and the blast from the heaters. As they began to sweat, adults and children shed their heavy winter clothes.

One young boy had squeezed into a compartment where eight people were sitting across from each other. He was joined by his mother, older brother, and older sister. Sitting on his mother’s knee, he played with a slice of bread and then pulled open a plastic bag holding bread, a tangerine, and soup handed out at an aid center.

One mother laid her child down to change its diaper. A girl leaned on her mother’s shoulder and briefly closed her eyes. The meow of a cat could be heard from another compartment down the way. A shaggy dog lazed next to its owner and snuffled in its sleep.

A few girls clung to the windows, gazing idly at the foreign landscape racing past them. Anna’s youngest daughter, 7-year-old Olesia was playing excitedly with a friend she had made on the train.

After Anna’s husband drove them to western Ukraine on Feb. 25, the day after the war began, she didn’t immediately cross the border. She and her daughters spent nearly two weeks at a neighbor’s house in the area.

“I thought the war would be over right away. I figured we’d be able to return home soon. I thought I needed to go somewhere a little safer for my children’s sake, somewhere they could study. After keeping an eye on the situation, I decided to go to another country in Europe.”

As of March 13, there were 1.85 million Ukrainian refugees still inside the country’s borders — internally displaced people.

But despite Anna’s predictions, the war has become protracted for reasons both simple and complex. Russian President Vladimir Putin’s plan was to insert paratroopers and armored units in Kyiv at the beginning of the war to deliver a decapitating strike against the Ukrainian government. But that plan was foiled by staunch resistance from the Ukrainians.

Since then, the Russians’ merciless offensive has continued against the capital of Kyiv; the second-largest city of Kharkiv, along with Chernihiv and Sumy, in the northeast; and the port city of Mariupol, on the Sea of Azov.

There are continuing reports of “humanitarian corridors” that have been established to evacuate civilians. But since fighting is continuing nearby, refugees’ safety is not guaranteed. As Russian forces encircle major cities in Ukraine, block shipments of food and medical supplies and continue their bombardment, there are fears that the Russians mean to break the Ukrainians’ will to resist.

That was the method used by Russian forces to retake Aleppo, Syria’s second-largest city in the north, during the civil war in the country.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy gravely acknowledged in a press conference on Saturday that several small towns no longer exist.

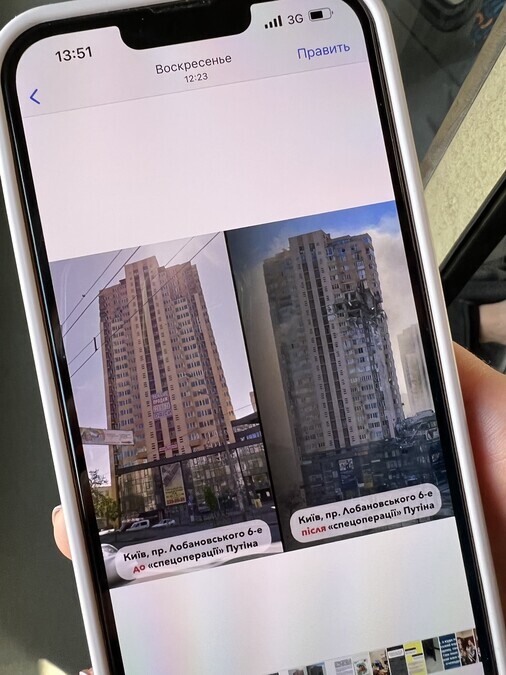

The refugees on the train let out long sighs as they monitored the situation in their home country on their phones in real time.

“I’ve been checking the news every minute, every moment, since that day. I’m so scared to fall asleep. It’s terrifying to think what might have happened overnight when I wake up in the morning to check the news,” Anna said, her voice trembling.

“I’m constantly refreshing Facebook messenger to check when my husband and younger brother were last online. When it says they were last active an hour ago, I feel relieved that they’re still OK.”

Anna loaded an album and showed me pictures of her husband and younger brother. Behind her husband in the photograph, I could see soldiers in military outfits. Her younger brother was wearing army fatigues, too.

On March 10, while Anna was riding the train to another city in Poland, the Russian and Ukrainian foreign ministers met for the first time since the war broke out in the Turkish port city of Antalya, abutting the Mediterranean Sea. But the meeting didn’t work out as hoped.

In a press conference following the meeting, Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba said that no progress had been made and that the Russians hadn’t brought anything new to the table. Kuleba also said that Ukraine would never surrender, underlining the Ukrainian people’s will to resist.

The greatest concern for the international community is the fate of more than 400,000 civilians in the besieged city of Mariupol, where essential goods have run out. According to a report by the UN’s Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, Russian military attacks on city infrastructure have left residents without electricity and hot water.

Three civilians, including a young girl, were brutally killed when the Russian military bombed a maternity and children’s hospital in Mariupol on March 9. But in the same press conference on March 10, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov asserted that the maternity hospital had been occupied by Ukrainian radicals, while the Russian Embassy to the UK claimed that a blood-spattered pregnant woman who had been rescued from the hospital’s wreckage was a “beauty blogger” acting a part.

Putin himself blamed the rising tally of civilian casualties on radical elements in Ukraine during a phone call with the leaders of France and Germany on March 12.

“What’s your name?”

“Viktor!”

I quickly got to know the children I met on the train of refugees. They ran around inside as if they were on the playground.

I couldn’t help wondering how much further they’ll have to go, and when they’ll get to return home.

By Noh Ji-won, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 2Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 360% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 4[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 5Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 6[Editorial] Stagnant youth employment poses serious issues for Korea’s future

- 7Inside the law for a special counsel probe over a Korean Marine’s death

- 8[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 9[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 10[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press