hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

In opting for bloc diplomacy, Yoon puts Korean Peninsula peace at stake

“Other national leaders work hard on pursuing diplomacy of national interest, yet President Yoon Suk-yeol appears to be singularly waving the flag of values diplomacy."

“The Indo-Pacific strategy of the government of South Korea… Well, it’s to the point that it’s hard to tell whether it’s South Korean diplomacy, US diplomacy or Japanese diplomacy. Diplomacy without a nationality isn’t diplomacy.”

This is former unification minister and State Council member for unification, diplomacy and security affairs Jeong Se-hyun’s general take on President Yoon Suk-yeol’s recent diplomatic tour of Southeast Asia, as expressed to the Hankyoreh on Wednesday.

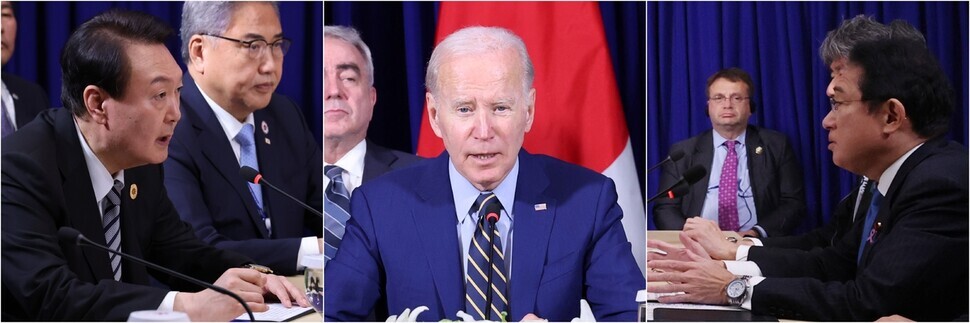

During the ASEAN summit in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and the G-20 summit in Bali, Indonesia, from Nov. 11 to 15, Yoon held bilateral summits with the United States (Nov. 13), Japan (Nov. 13) and China (Nov. 15).

In particular, he held a formal, 50-minute face-to-face meeting with Fumio Kishida, which followed his “brief meeting” with Kishida on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly in September, and he held his first face-to-face meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping, a 25-minute talk.

These meetings were very significant in that they reopened the sluices of bilateral summit diplomacy between South Korea and Japan and South Korea and China after bilateral summits. Bilateral summits between the three had been suspended for two years and 11 months due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The last bilateral summit with Japan had been the meeting between former President Moon Jae-in and late Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in Chengdu, China, on Dec. 25, 2019, while the last one with China had been the meeting between Moon and Xi in Beijing on Dec. 23, 2019.

However, looking at what was said during the latest summits, there is much to be concerned about. This is particularly so with the so-called “Korean Indo-Pacific strategy,” first revealed by Yoon on Nov. 11, and the Phnom Penh Statement on Trilateral Partnership for the Indo-Pacific, adopted on Nov. 13 as the first ever joint statement by the leaders of South Korea, the United States and Japan.

The Korean Indo-Pacific strategy and the Phnom Penh Statement represent the essence of “Yoon Suk-yeol diplomacy” as revealed during the latest tour. In fact, national security adviser Kim Sung-han on Wednesday pointed to the announcement of an “independent Indo-Pacific strategy” as the top achievement of the tour, and to the Phnom Penh Statement as the fourth biggest achievement, saying that the moves had “set important milestones in our diplomacy."

The problem is that critics have labeled this “Americanization of South Korean diplomacy” and “diplomatic documents written in American language.” The line in the Phnom Penh Statement about a “free and open Indo-Pacific, that is inclusive, resilient, and secure” is the central slogan of Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy.

Yoon’s Indo-Pacific strategy is the same as the Indo-Pacific strategy first proposed by late Japanese Prime Minister Abe to contain China — a strategy later realized by the Trump and Biden administrations — beginning from the very name. The Phnom Penh Statement is an open declaration to “align our collective efforts” and “work together” in the execution of an Indo-Pacific strategy where the hierarchy between South Korea, the United States and Japan is quite clear, with Washington on top.

Moreover, the Phnom Penh Statement takes straight aim at China and Russia by stipulating strong opposition to “unlawful maritime claims, militarization of reclaimed features, and coercive activities,” and by condemning “Russia’s unprovoked and brutal war of aggression against Ukraine” and “Russia’s nuclear threats to coerce and intimidate."

The three leaders’ agreement to create a new “dialogue among the three governments on economic security” is also an open declaration to gravitate towards Washington as the United States and China compete over hegemony and strategy and re-order supply chains. This is an abandonment of the “balanced diplomacy” of the Moon Jae-in administration, which tried to broaden Seoul’s autonomous space between the United States and Japan on one hand and China and Russia on the other, taking into consideration the Korean Peninsula’s geopolitical and geo-economic position as a nodal point between the Asian mainland and the Pacific maritime region, as well as the Korean peace process.

Yoon has essentially broken away from the foreign policy strategy of successive governments that have worked to “broaden the path northwards to the Asian mainland,” a strategy pursued by both progressive and conservative governments since late President Roh Tae-woo announced his “Nordpolitik” strategy of 1988.

This diplomatic orientation of Yoon was on clear display even in his bilateral summits with the United States, China and Japan. That is, while South Korea, the United States and Japan solidified their partnership, the South Korea-China relationship remained touch-and-go.

Firstly, there was a clear difference in time allotment for the talks. Yoon talked with US President Joe Biden for 50 minutes and Kishida for 45 minutes. But with Xi, he talked for only half as long — 25 minutes. This discrepancy in time allotment is only magnified when you look at what was said during the talks.

For example, the leaders of the United States and Japan, on one hand, and China on the other, responded in clearly different ways to Yoon’s leading unification and North Korea policy, his “audacious initiative.” Biden and Kishida expressed clear support for the goal of the “audacious initiative” through the Phnom Penh Statement. On the other hand, Xi expressed a will to “support and cooperate with” the plan, but added the caveats, “North Korea’s intentions are key” and “if North Korea responds favorably.”

However, North Korea has already publicly rejected the “audacious initiative,” with Kim Yo-jong, vice department director of the Workers’ Party of Korea, slamming it as “a replica of ‘denuclearization, opening and 3 000’ raised by traitor Lee Myung Bak 10-odd years ago only to be forsaken as a product of the confrontation with fellow countrymen,” and promising “not sit face to face” with Yoon.

Given that Xi undoubtedly knows this, it’s hard to consider his statement as an expression of support for the “audacious initiative.” Regarding this, a high-ranking South Korean presidential office official said Xi’s statement could be read as “a positive message that China will lend full support as soon as North Korea accepts the plan.”

Rather than preparing negotiations on the North Korean nuclear issue and other matters, Yoon worked harder to broaden the base of international cooperation to pressure North Korea. Typical of this is how, during his summit with Biden, Yoon extracted a promise from the US president that the two sides would “respond with overwhelming force using all available means” if North Korea used a nuclear weapon, but when speaking to Xi, he asked that China play a “more active and constructive role.” However, Xi suggested another approach, expressing hope that Seoul would “actively improve North-South relations.”

Most importantly, Xi called for “speeding up negotiations” on a bilateral free trade agreement, while stressing the need to “oppose politicizing economic cooperation and overstretching the concept of security on such cooperation.” He also said the two sides should “jointly practice true multilateralism.”

“True multilateralism” is a concept often used by China when criticizing “mini-multilateralism” and “Indo-Pacific strategies” such as the US’ AUKUS and Quad frameworks. Xi’s message was that he opposes Yoon’s establishment of an Indo-Pacific strategy and a trilateral economic security dialogue with the US and Japan — suggesting that some rough weather may lie ahead for South Korea-China relations.

Various factors in Northeast Asia — South Korea’s closeness with the US and Japan, the rocky state of its relations with China, and the major crossroads that appears to be looming for its relationship with Russia — are poised to have a negative impact on its paramount tasks, namely resolving the North Korean nuclear issue through dialogue and negotiations and creating a permanent peace regime.

“In a Northeast Asian climate where ‘wedge diplomacy’ and ‘bloc diplomacy’ are on the ascendancy, it becomes more difficult to manage inter-Korean relations and the Korean Peninsula’s political situation in general, and it leaves a narrower space for South Korea to maneuver diplomatically,” said one veteran figure from the field of foreign affairs and national security.

A former senior government official noted, “In the wake of the Ukraine situation, South Korea’s trade with Russia has fallen by 17%, while Japan’s has actually risen by 13%.”

“We need to be looking at the reality of practical diplomacy, rather than getting taken in by talk of ‘values diplomacy,’” they urged.

But in a Facebook message posted from his presidential aircraft on his return flight, Yoon repeatedly emphasized a “spirit of freedom and unity.”

His words signaled that he only intends to double down on a divisive foreign affairs approach billed as “values diplomacy.”

By Lee Je-hun, senior staff writer; Kim Mi-na, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 3After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 4[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 5[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 6Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 7US exploring options for monitoring N. Korean sanctions beyond UN, says envoy

- 8US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 9[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 10Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76