hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

How a survival-of-the-fittest culture kindles jingoism among Koreans, Chinese

“We spend years studying hard, passing exams, finding a good job, buying a house — in this process, meaning has been externalized. [. . .] We need to make it so that the public can discover the meaning in the small things of everyday life. Otherwise, everyone just wants their children to go to Beijing.”

This was the assessment of Chinese society put forward by the Chinese-born anthropologist Xiang Biao, director of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, in his 2020 book “Self as Method.”

The book reflects Xiang’s research approach as someone who has always preferred delving into the concrete aspects of life to grandiose discourse. It has also been quite popular in China, where it has sold over 200,000 copies. In late October 2022, the book was published in Korean translation by Geulhangari under a title that translates as “The Loss of the Periphery.”

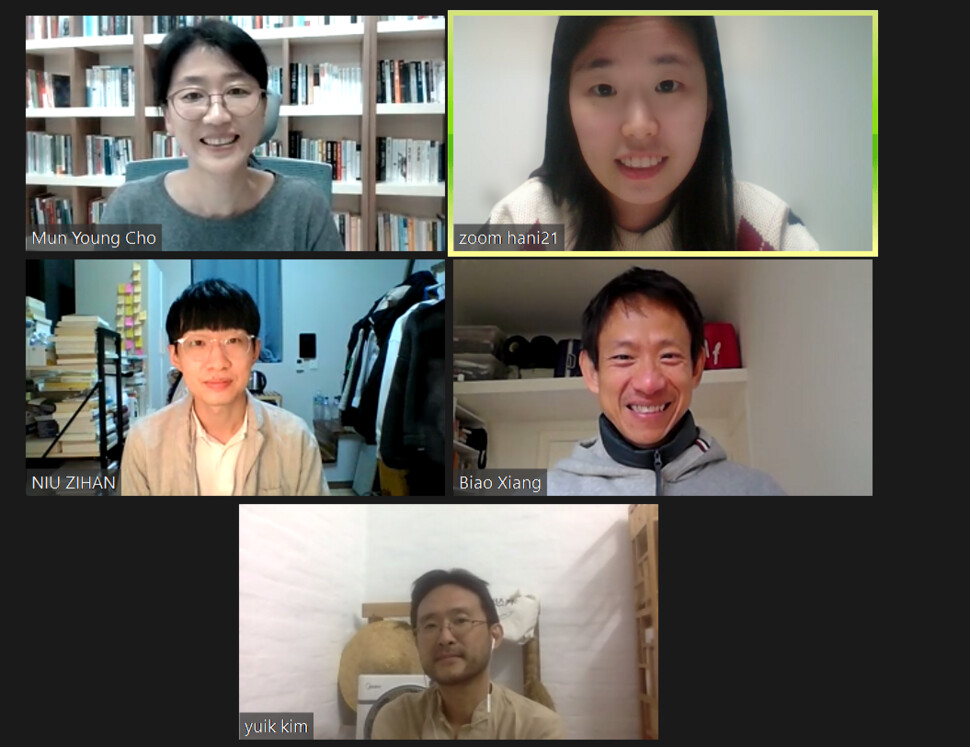

What connections does the overheated competition in China that Xiang explores bear with the situation in South Korean society? Xiang sat down for a videoconference with Yonsei University cultural anthropology professor Cho Mun-young — who wrote a recommendation for the book — to discuss the cultures of competition in South Korea and China.

The intense battle in China to move from the periphery to the center dates back to 1978 and the sudden opening of the country’s markets.

“The reforms and openness resulted in 1 billion people being thrust into market competition more or less simultaneously,” Xiang explained. “Everyone believed that the opportunities rushing by them might be the last, and they developed a willingness to defer present happiness for the sake of a better future.”

In this case, “center” and “periphery” are analogies referring to the places where social resources are mainly concentrated and those where they are not.

Four decades have passed since this intense competition for resources began. As fatigue has built throughout Chinese society, many have become more vocal in their scorn for competition.

Some of the recent coinages in China include the term “nei juan,” meaning “dragged into competition,” and “985 reject,” which refers to someone who has graduated from one of China’s elite universities (the “985 Project”) but is unable to find good employment.

“The message people want to share now is, ‘I’ve gone through all this competition, and even my most basic desires haven’t been met,” Xiang said.

Education has likewise been turned into a vehicle for the heated competition for class mobility. It is not rare to hear reports of suicides by students taking college entrance exams or studying for their master’s or doctoral degree in China.

“The reason isn’t that they failed at the competition,” Xiang explained. “It’s because they couldn’t account for their competition failures within the dominant discourse in Chinese society, or they couldn’t explain why they didn’t want to be part of the competition.”

The climate is not much different from South Korea’s with its experience of accelerated growth.

“Young people in Korea are also facing what they describe as being ‘stuck on a treadmill with no “off” button’ — where it isn’t clear what the rewards of the competition are or when it ends,” Cho said.

“These are young people who have acquired educational capital, but they’re experiencing extreme employment insecurity amid the clear labor market division between regular and irregular jobs. They’ve cast themselves as the ‘disadvantaged,’” she explained.

At the same time, Cho cautioned against excessively generalizing the sense of “fatigue” associated with the race to join the upper class.

“That’s an issue of young people who have some level of educational capital,” she said. “There’s a difference in the degree of societal rewards between the competition fatigue that a platform delivery worker experiences and the competition fatigue that a young person faces in the IT industry.”

“There are more discussion forums today where young IT workers and university students can talk about their anxieties, but we still lack understanding of the young workers who lost out in the competition early on,” she added.

She also added that many young people in Korea have consistently created their own discourses that break away from mainstream discourse, such as the basic income movement and the climate justice movement.

Xiang explained that in China, such attempts are not as common, and, in the case of many, it is difficult to imagine a life without competition.

“China has seen the rise of a term, ‘tangping,’” — a neologism meaning that it’s better to lie down and do nothing than participate in meaningless competition — “but, this sentiment doesn’t egg people on to resist competition, rather, it is just a way for people to get on terms with their feelings,” he said.

“Activists who have escaped from the clutches of competition or people who turn their backs on the city and go back to farming are likely to be a small elite. Currently, the youth are only aware of the feeling that they have failed, but they don’t understand the situation they are put in. They need to be given tools to analyze that situation.”

The gap that emerges from a lack of self-understanding is often patched up by “understanding others.” A good example of this is nationalism. “Little Pink” (xiǎo fěnhóng), a term used to describe jingoistic Chinese nationalists who are fiercely active on the internet, aggressively criticizing “enemies” who write anything that may affect China’s authority.

A case in point is the case in which Korean singer Lee Hyo-ri appeared on a TV show in 2020 and said, “How about we use ‘Mao’ as a stage name?” only to be the target of Little Pink. Her social media accounts were basically paralyzed by the malicious comments left by Little Pink.

Xiang believes that this phenomenon can also be credited to the “lack of self-philosophy.”

“We’re all just normal people who have nothing to do with the power of the state. We’re not familiar with national policies, too. Then why do we have to see the world from a nationalistic perspective? The urge to believe in the need for a “Chinese discourse” might stem from an unsatisfactory personal lifestyle. One only feels safe when donning a hat symbolizing the enormous state and its people.”

In Korea, “gukppong” — Korea’s own term for jingoistic attitudes, drawing on the metaphor of being as high on the nation, as one would be on a narcotic — is seeing a resurgence thanks to the internationally lauded Korean response to the COVID-19 pandemic and the Korean wave. While there have been fewer cases of Korean nationalists going after foreign influences, videos that boast of Korea’s respectable international status are a dime a dozen online.

“Political correctness,” a term used to describe the concept of avoiding any sort of behavior that may cause offense or disadvantage to members of particular groups in society, and which has soon turned into a new social value, is also becoming an important factor of this debate.

Xiang Biao says that political correctness has its limits when it comes to explaining oneself. This is because a neatly organized opinion is not the same as the experiences an individual goes through.

“The values of the highly educated middle class almost monopolize public discourse and are fast becoming the only way to express the ‘truth.’ People aren’t averse to political correctness because it is wrong or false. They simply believe it to be hollow. It is impossible to express yourself through something like this,” said Xiang.

“It is time for everyone to start writing about their own experiences through ‘real’ methods. When there are enough experiences, the truth will start to emerge. At that point, people will stop being petty about issues and grow to see what is true and add that to what is really important.”

Fragmentary individual opinions about controversial issues such as sexism or global warming are shared on online communities. However, online communities also show the risks that come with explosive and immediate communication.

“It takes a lot of time for individuals with very different opinions to reconcile. There needs to be enough time to argue and debate, and one needs to give their opponent time to reflect. This almost never happens online. If they don’t throw their opinions explosively at their opponent, they begin to feel anxious and think that they are losing,” said Cho.

The focus on grabbing instantaneous attention online also likely distorts communication.

“Social media does not deal deeply with any subject, and only focuses on symbolizing and commodifying it, as if it is dealing with a provocative TV show. That’s how it makes subjects distributable. Within that space, we only state that we ‘like’ or ‘dislike’ something, as if we were using emojis. We don’t exchange opinions about why a person is the way they are,” says Xiang.

What approach should we take in order to transcend consumptive communication and start to really understand ourselves and other people? Xiang suggests that individuals look around themselves.

“Nowadays, people only think of themselves through social atomism. Therefore, they only think about themselves or make grandiose comments about big phenomena. They only focus on themselves, their families, or on the world. But the meaning and dignity of the self can only be retrieved through relationships, not the individual. A being’s dignity is not a natural thing but is made in the process of building relationships around them,” he says.

The “periphery” central to Xiang’s thought is the physical community around individuals, such as their neighbors, store managers of their regular shops, apartment security guards, et cetera. This sort of periphery can serve as a middle ground that connects the small individuals to the bigger world.

Xiang titled his book “Self as Method” so that people could use the “self” instead of others to understand the world. However, the “self” here doesn’t refer to “individuals who have clear boundaries,” but, “a network that changes every time through various relationships with other people,” as Cho wrote in her blurb for the book’s Korean translation.

“Seeing how different the lives of one’s ordinary neighbor, such as security guards or cleaners, or seeing what sort of argumentative skills are used in squabbles between neighbors can be interesting topics of research. Students may think that London or New York is full of art while the countryside is boring, but if one takes this sort of approach, you can see that the countryside also has plenty of rich narrative,” writes Cho.

“The key is to see the world through your own gaze, instead of using something that is handed to you from outside sources.”

Cultural anthropology, which looks deeply into human life and history, can prove a useful tool.

Xiang suggested that young people could participate in acts such as writing non-fiction about their surroundings, or reading science fiction, which can take the ordinary and turn it upside down, in order to understand their periphery. Cho has also run projects in university lectures to enable students, who were finding it difficult to understand each other, to interact and discover questions to ask one another.

A new periphery created by digital platformsCho also emphasized on the possibility of new “peripheries” made through digital platforms. It is hard for young people to become attached to physical places, due to high housing prices and frequent movement from one place to the other.

As a second-best option, more and more people are turning to a “periphery” online.

“I’ve met a lot of youth who’re making their own ‘peripheries’ online. For example, young women artists who live in Busan often communicate more with young women artists in Seoul via the Internet, rather than getting to know local artists. When I asked why that was the case, they said it was hard to bond with Busan born-and-bred artists since those communities are still very patriarchal and network-oriented by nature. It seems that there’s a shift from only focusing on their physical whereabouts to choosing and making places, both online and offline, where they can really communicate and learn to love,” she said.

Master of global localityWho is Xiang Biao?

Xiang, who currently serves as director of Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, first gained academic attention for his master’s thesis, “Researching Zhejiang Village,” which focused on the residences of workers from Zhejiang Province near Beijing, China for six years. “Global ‘Body Shopping,’” his Ph.D. thesis, which focused on the relationship between global economic exchanges and regional “locality” based on the immigration of IT workers from India to foreign countries, received the Anthony Leeds Prize, an award that is considered a great honor from the American anthropology community.

His 2020 book, “Self as Method” has emerged as a must-read for the Chinese public, selling more than 200,000 copies. He was also a professor of anthropology at Oxford University.

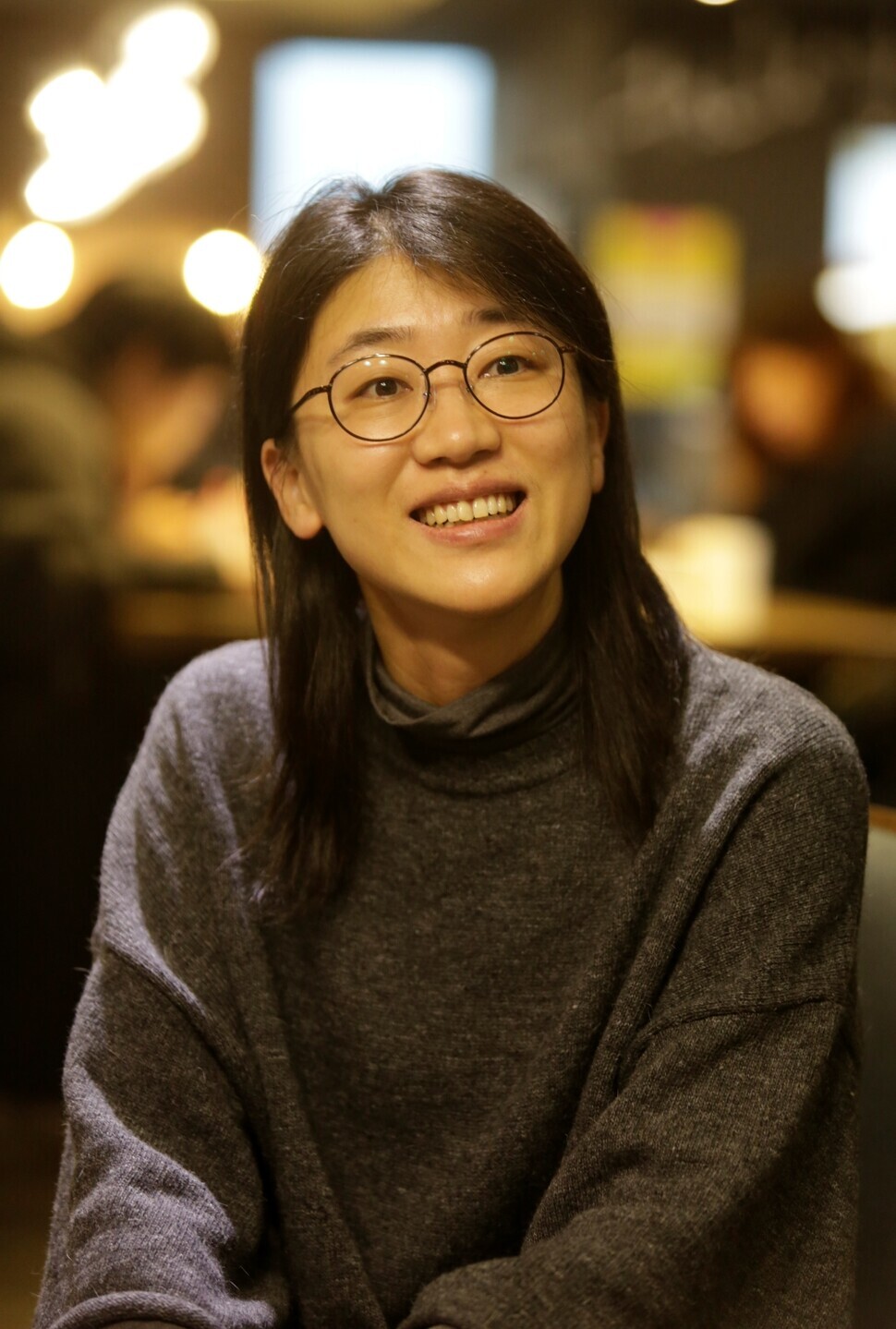

Cho Mun-young, a professor of cultural anthropology at Yonsei University, is a researcher who has devoted herself to researching poverty mainly in Korea and China. Her master’s thesis on the relationship between poverty and welfare in Nan-gok, the poor area of Gwanak District, Seoul gained much attention. Since then, she has written about how socialist workers in China’s Dongbei region became impoverished as her doctoral thesis. In 2014, she won the Anthony Leeds Prize for writing a research paper on urban poverty in northeastern China.

By Shin Da-eun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 260% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 3Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 4[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 5Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 6AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 7S. Korean chaebols comprise 84% of GDP but only 10% of jobs

- 8Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 9[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 10[Reportage] New funeral culture taking hold in South Korea