hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Korea’s atrocities in Vietnam, in the words of those who saw and survived them

In a historic ruling, a victim of a civilian massacre perpetrated by South Korean soldiers during the Vietnam War has won a compensation lawsuit against the South Korean government.

This marks the first time that South Korea, the perpetrator, has been held legally culpable for the civilian massacre that took place in Phong Nhị Village, Điện Bàn District, Quang Nam Province in 1968.

On Feb. 7, Park Jin-su, the presiding judge in the 68th civil division at the Seoul Central District Court, ruled in favor of plaintiff Nguyen Thi Thanh, 63, in her lawsuit filed against the Korean government.

The court ruled that South Korea must pay the plaintiff close to 30 million won (US$24,000) in compensation and pay for the damages incurred due to the delay in compensation.

“We acknowledge the fact that soldiers of the 2nd Marine Infantry Division (known as the Blue Dragon Division) shot the plaintiff’s family during Operation Giant Dragon and forcibly rounded up the plaintiff’s mother with other people before shooting them,” the court ruled.

The Hankyoreh 21 reported these facts in Issue No. 1256 published on March 29, 2019, titled “South Korean soldiers passed out candy to assemble villagers.”

At the time of the massacres, the Blue Dragon Division killed many civilians and burned villages under the pretext of an operation to facilitate the search for the Viet Cong.

It was only in 2019 that 103 bereaved family members and victims from 17 villages submitted a petition to the Blue House. They demanded a fact-finding investigation and an official apology.

In this article, we reintroduce the petitions of some of these victims through previously published articles that explained what happened during the massacre.

“Screams in the village every night”

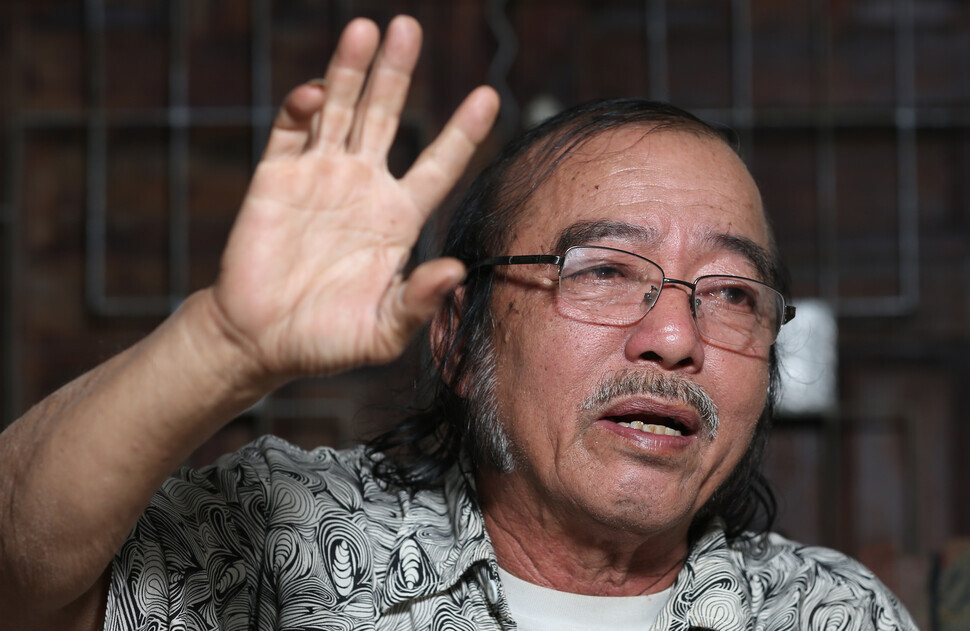

Nguyễn Tan Quy

Massacre at Tây Sơn Tây village, Duy Hải commune, Duy Xuyên District, Quảng Nam Province (massacre at Old Mr. Nho’s air raid shelter)

Date of birth: Registered as 1942; actual birth year 1940

Date of massacre: Nov. 12, 1969

Details of massacre: I was eating breakfast with my family at around 6 am when we heard the sound of shells. I was a member of the guerrillas, and the young men from the village and I fled to avoid the South Korean troops.

The villagers and family members remaining behind in the village hid in the air raid shelter at Old Mr. Nho’s house. The South Korean soldiers soon swooped in on the village. They dragged the residents out of the air raid shelter and assembled them in a bamboo grove next to it.

The soldiers first asked the residents if they were “VC” (Viet Cong). Then they opened fire on them. The people who were shot died on the spot. The South Korean soldiers threw a grenade toward the people who hadn’t come out of the air raid shelter.

After the soldiers left, the other young people and I returned to the village around 5 in the afternoon. We went looking for our family members among the bodies, which were so badly damaged that it was hard to make out their features. My mother Lê Thị Lạc (then 62), my wife Ngô Thị Khuê (23), my two daughters Nguyễn Thị Huệ (5) and Nguyễn Thị Bé (1), and my son Nguyễn Tấn Sang (3) all died that day. I was 24 at the time.

Not knowing when the South Korean troops might return to the village, I had to bury my family and leave the village in a hurry. I wrapped the bodies up in scraps of parachute and raincoats I’d picked up from the area, and I buried them quickly in the ground. I placed five stones there so I’d be able to find the gravesite again later on, and I left the village.

Fortunately, the markers were still there when I returned to my hometown after the war ended in 1975, and I was able to give my family members a funeral. At night, I could hear people crying and screaming in the village. I couldn’t be there anymore, so I moved to another village.

My neighbors also couldn’t bear to live in the village. They began leaving one after the other; today, the village has disappeared completely.

What I want from South Korea: I want the South Korean government to acknowledge and apologize for the South Korean troops’ massacres of Vietnamese civilians before it’s too late.

“South Korean soldiers passed out candy to assemble villagers"

Huỳnh Thanh Quang

Massacre at Cầu village, Bình Hòa commune, Bình Sơn District, Quảng Ngãi Province (Bình Hòa massacre)

Date of birth: March 3, 1959

Date of massacre: Oct. 25, 1966 (solar calendar Dec. 6, 1966)

Details of massacre: These are my family members who were killed by South Korean soldiers: my grandmother Đỗ Thị Quảng (then 60 years old); my mother Nguyễn Thị Niêm (28); my two younger sisters Huỳnh Thị Lem (5) and Huỳnh Thị Luốc (3); my two nephews; my aunts Bùi Thị Ngải, Bùi Thị Chi, and Bùi Thị Dung; my three cousins Huỳnh Đông, Huỳnh Nga, and Huỳnh Hậu; and two female relatives both with the same name, Huỳnh Thị Thương and Huỳnh Thị Thương.

My father had died the year before the massacre, and our family members were living separately. I was 7 at the time and living with my mother’s father in a strategic hamlet near the village. (Strategic hamlets were special resettlement villages, which had barbed wire or bamboo fences surrounding them to separate themselves from the Vietcong in the name of the pacification of the Delta.) My mother and two younger sisters had stayed behind in our village.

So I didn’t witness the massacre firsthand. Later, I would hear from my grandfather and neighbors that our family members had been massacred; they said the South Korean troops assembled residents by passing out candy and other things. I couldn’t go to the village after the massacre because it was too dangerous. My uncle survived the massacre and gathered the bodies; it was only later that I would see the humble family grave where they were hurriedly buried.

The South Korean soldiers also set fire to my family’s house in Bình Hòa and all their possessions. The massacre left me a war orphan, and I went on to live with my mother’s father and aunt in Bình Thời commune, about 10 kilometers from Bình Hòa commune. Just as I was finally learning to read, I had to quit school because of my family’s financial situation. I can remember being yelled at by my father when I was a boy for crying and looking for my mother.

What I want from South Korea: Even though time has passed and made this incident into a thing of the past, bereaved families and victims such as myself still live with the pain left to us from that day. I hope that Korea will, with the bare minimum of good conscience, help the Vietnamese victims heal their wounds.

“Thump! Thump! Thump! The sound of my dying father’s drumming”

Đặng Minh Khoa

Massacre at Thuận Trị village, Duy Hải commune, Duy Xuyên District, Quảng Nam Province (massacre of the Đặng So family)

Year of birth: 1950

Date of massacre: Feb. 16, 1969

Details of massacre: “Thump! Thump! Thump!” I could hear drumming outside the house. With one day till the Lunar New Year holiday, my father, Đặng Sỏ (then 59) was preparing for a memorial service at the shrine in front of our house.

But out of nowhere, Korean soldiers suddenly came into the house. They pointed their guns at my father, who loudly protested their presence, and pulled their triggers. My father tried to warn his fellow villagers of danger by beating the drum with his dying breath.

The sound of gunshots alarmed my family, who then ran out of the house. The Korean soldiers, who had been standing in front of the door, killed all nine members of my family and set fire to the shrine.

My sister, Đặng Thị Huỳnh (then 26) managed to flee from the scene of the massacre to come out alive. On that day I lost my father, my mother Nguyễn Thị Thêm (57), older brother Đặng May (34), younger sister Đặng Thị Mỹ Hương (16), my two sisters-in-law, Lâm Thị Ưng (32) and Hồ Thị Tửu (30), niece Đặng Thị Mỹ Yến and two unborn nephews who were being carried by my sisters-in-law to Korean soldiers. The Korean soldiers buried the bodies in secret.

This is all that I was able to hear from the sole survivor, my sister, Đặng Thị Huỳnh. I was 19 years old at the time. As I was studying in Saigon (Ho Chi Minh), I was unable to return to my hometown even for New Year’s, because of the war.

After hearing the sad news from my sister, I ran straight to my home in the Duy Hải commune. I could not bring myself to enter the house, and I was caught by the South Vietnamese police while wandering around the area. I spent eight months in prison in Hoi An for being part of the “student movement.”

After being released from prison, I returned to Saigon and only went back to my hometown after the Vietnam War ended in 1975.

What I want from South Korea: I have done everything I can to publicize the atrocities committed by the Korean troops who slaughtered my family. I do not want any material or financial help from Korea. My demand is that the Korean government acknowledges the crimes committed by the Korean military and gives an official apology to the victims and their bereaved families.

“Rain mixed with blood came up to my ankles”

Lê Thanh Nghị

Massacre at Trảng Trầm village, Bình Dương commune, Thăng Bình District, Quảng Nam Province

Year of birth: 1949

Date of massacre: Nov. 12, 1969

Details of massacre: The sound of guns had been constant since the day before. It was the sound of the Korean military shooting at a Viet Cong (VC) battalion. The next morning, the sound of guns stopped. Soon after, Korean troops entered the village.

The Korean troops dragged 74 villagers to the middle of an empty field, shot them and threw grenades to massacre them. As the leader of a guerrilla unit, I was monitoring the Korean military’s movements, and witnessed the atrocity from a mere 500 meters away. I was 20 at the time.

That night, I went to collect the dead bodies, which were stacked in piles. Rain mixed with blood came up to my ankles. Seventy-three people lost their lives. Only an 11-day-old newborn baby miraculously survived. That day I lost my mother Phan Thị Nguệ (then 47), three younger sisters Lê Thị Yên (16), Lê Thi Di (10), Lê Thị Lần (8), my older aunt, my younger aunt and her three children, my younger cousin and her three children, my sister-in-law and her two children, and my paternal aunt and her two children to the Korean soldiers.

For as long as I live, I will never forget the moment when I had no choice but to watch my family get slaughtered. I still have nightmares and wake up terrified. As a guerilla soldier, I stood on the battlefield with nothing but revenge in my heart toward the Korean military. After the massacre, the bodies of 18 members of my family (excluding the baby that my paternal aunt was carrying) were recovered. However, American soldiers bulldozed the entire village starting in 1970, which means there are still nine graves to be found.

What I want from South Korea: Many families were massacred because of Korean soldiers. The Korean government should pay the bereaved families and victims the appropriate amount of compensation — an amount that will make up for the pain and the loss that the victims and bereaved had to endure their whole lives.

By Ku Dool-rae, staff reporter; Joh Yun-yeong, staff reporter; Lee Seung-jun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 3Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 4BTS says it wants to continue to “speak out against anti-Asian hate”

- 5After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 6Gangnam murderer says he killed “because women have always ignored me”

- 7South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 8AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 9Ethnic Koreans in Japan's Utoro village wait for Seoul's help

- 1046% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds