hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Xi and Putin re-up their “no limits” cooperation as world’s blocs become entrenched

After previously wrestling with the question of whether to distance China from Russia over the war that erupted in Ukraine in late February 2022, President Xi Jinping signaled even greater closeness with a visit to Moscow this week.

The message Xi sent points to a strategic decision to counter the US- and European-centered liberal global order with a “multipolar” system that China and Russia each play pivotal roles in shaping.

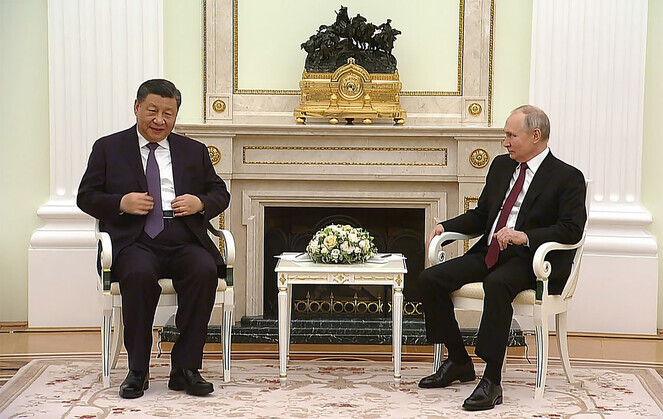

Sitting down together for a summit for the first time in six months, Xi and Russian President Vladimir Putin committed to strengthening their strategic partnership and formed an economic cooperation plan with a target date of 2030.

The two leaders were all smiles as they met and shook hands at the Kremlin on Monday afternoon, referring to one another as a “dear friend.”

In a message of gratitude, Putin said, “[A]ll of our Chinese friends devote much attention to Russian-Chinese relations, taking a fair and balanced stance on the majority of topical international issues.”

Xi responded by saying the two countries have “many overlapping or similar goals as we move forward.”

Remarking on Chinese concerns about the war in Ukraine, Putin said that Russia had “carefully studied” Beijing’s suggestions concerning the “acute crisis in Ukraine,” indicating that Moscow has been seriously concerning the mediation plan submitted by Beijing on Feb. 24.

But despite the cordial mood between the two leaders that day, the closeness between their two sides has been strained by the war in Ukraine.

In a meeting at the opening ceremony for the Winter Olympics in Beijing on Feb. 4 of last year, they issued a lengthy declaration stating that there were “no limits” to their friendship and no areas where they could not cooperate.

Their statement sent the message that they were obliged to raise the level of their partnership in response to the activities of the US and other Western countries, which had been expanding NATO and using frameworks like AUKUS and the Quad to hem them in.

But despite the “no limits” pledges, cooperation did not proceed for some time. The reason was Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February of that year.

Unsettled by the move, China maintained a stance of neutrality and declined to provide the weapon support that Russia wanted. For Xi, the invasion created an awkward situation at a key moment when he was gearing up for his third term as China’s head of state.

Relations between the two leaders were also strained. Meeting with Putin in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, when the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit was held there last September, Xi only said that China is “willing to make efforts with Russia to assume the role of great powers, and play a guiding role to inject stability and positive energy into a world rocked by social turmoil.”

Compared with the mood seven months earlier, the remarks were downright frosty — enough so for Putin to state that he “understood China’s questions” about the war in Ukraine and would “explain our position on them today.”

But after failing to improve relationships with the US owing to the “balloon war” sparked by China in early February, Xi ultimately opted to step up Beijing’s relations with Moscow.

After his third term as China’s president was confirmed in mid-March, Xi’s first overseas stop was Moscow. Having secured another five years in office, he is responding to the imperative posed by the confrontation with the US by embracing Russia again after the previous awkwardness. Xi’s visit to Russia was his first in nearly four years, the last having come in June 2019.

Putin welcomed the visit with open arms. With Russia facing harsh economic sanctions from the US and Europe since the invasions, China has been the sole source of support it can rely upon.

China imports Russian crude oil and natural gas and exports daily essentials that Russia needs. In the process, Russia has been able to duck being dealt a devastating blow by the US and European economic sanctions.

In a piece published Monday in the Chinese Communist Party-operated People’s Daily newspaper, Putin said that China-Russia relations had “reached the highest level in their history.” The same day, he reiterated his position that there were “numerous issues for economic cooperation” between the two sides.

But there are also many areas where their interests do not align — as evidenced by the events of 1969, when the two countries, which share a border stretching for several thousand kilometers, arrived at the brink of war over a border dispute. Internally, many in Russia have voiced concerns about relying too much on China.

In its response, the US bristled over the strategic closeness between the two sides. On Monday, Secretary of State Tony Blinken blasted China for providing “diplomatic cover” to Russia for its crimes.

John Kirby, the White House National Security Council coordinator for strategic communications, downplayed the significance of the closeness between Beijing and Moscow, calling it a “marriage of convenience [. . .] less than it is of affection.”

Instead of the “Kissinger approach” of the 1970s — where it sought to divide China and Russia to achieve victory in the Cold War — the US is opting to beef up its alliances in Europe and Asia. It has repeatedly sent the message that it is working resolutely to confront both China and Russia on two fronts.

With Beijing beefing up its strategic ties to Moscow, and with Washington signaling its continued aim of confronting them on two fronts, the “new Cold War” framework putting the US against China and Russia appeared certain to intensify.

By Choi Hyun-june, Beijing correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1South Korean ambassador attends Putin’s inauguration as US and others boycott

- 2Family that exposed military cover-up of loved one’s death reflect on Marine’s death

- 3Behind-the-times gender change regulations leave trans Koreans in the lurch

- 4Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 5Yoon’s revival of civil affairs senior secretary criticized as shield against judicial scrutiny

- 6[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 7Japan says its directives were aimed at increasing Line’s security, not pushing Naver buyout

- 8Marines who survived flood that killed colleague urge president to OK special counsel probe

- 9‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 10Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar