hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

When she was reunited with her birth family, she realized her entire adoption file had been false

Editor’s Note: To mark the 35th anniversary of the newspaper’s founding, the Hankyoreh is featuring the stories of 20 transnational Korean adoptees in several installments. May 11 was Adoption Day, and this year marks 70 years of international adoption from Korea.

South Korea is also the third country in the world, after Chile and Ireland, to launch a state-level investigation into human rights violations in the adoption process.

The Danish Korean Rights Group (DKRG) is the world’s largest community of Korean adoptees, with more than 650 members from 10 countries, including Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, and the US.

Since August 2022, the group has submitted 334 adoption cases to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea for investigation, leading to the opening of the investigation into human rights violations in the overseas adoption process in December 2022.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission plans to conduct a local investigation in Copenhagen starting in June. The attention of the estimated 200,000 Koreans who were adopted across the world is on the case.

The Hankyoreh respects the desire of international adoptees to restore truth and justice by looking into their history, which has been tampered with from their birth by instances of infant trafficking and record falsification.

These brief personal histories of 20 adoptees are accompanied by their hopes for the TRC investigation — that the truth is revealed, and they can reconcile with their past.

Visited the orphanage I had spent the first 6 months of my life at only to learn I\'d never been there

Betina. Adopted at 6 months old. Currently 49 years old. Denmark.

My name is Betina Jung-Hee.

According to my adoption files, I was born on Feb. 7, 1974, and my given name was Cho Jung-Hee. I was the result of an unmarried young woman who got pregnant by accident and gave birth to me, then (in desperation) left me in front of the Star of the Sea Catholic Children’s home with a paper slip with my birth date as the only information about my past. On Aug. 15, 1974, someone put me on a plane and I left Korea as a Korean child. On Aug. 17, 1974, I arrived in Denmark to become a Danish citizen.

Until November 2022 that was all I knew about what I left behind when I was adopted by my Danish parents as a 6-month-old baby back in 1974.

I grew up as an only child in a regular and pretty normal average Danish family. I had parents, I went to school, had a job, friends, a cat, and did all those normal things you do while growing up. But I always felt a bit different compared to other people and the people and culture that I grew up in. I can’t really describe it because looking back, it all seems like a big blur. Like a song you’ve forgotten the lyrics to but still know how to hum. All I know is that in the back of my head I always knew that I had to find out more about my past to find myself in the future.

Years went by and, to be honest, I was too scared to do anything about it. Mostly because my Danish parents were against me searching for my birth family and my past. So, apart from a few sparing attempts where I wrote and tried to correspond with some of the agencies and offices who have had something or anything to do with my adoption in Denmark and Korea, I fulfilled my adoptive parents’ wish while they were still alive. In 2015 my Danish mom died followed by my Danish father in 2018.

In 2019 I went back home to Korea to do a well-planned birth family search. I went to the Mapo police. I had DNA tests done. I had a translator. I went to community centers in the area where my birth mother supposedly lived when I was born. I went to the orphanage where I (according to my case file) stayed for the first six months of my life only to find out that I’d never been there. I found out that I was born in Seoul and that I’d never been to any orphanage — I’d been with my birth mother for the first three months of my life, and she’d brought me to KSS on May 9, 1974, where she left me.

I was not allowed to have a full copy of my case files without revisions or information about my birth family nor any further information about myself. It made me frustrated, and I knew that I had to follow up on this as soon as possible. I did a lot of hard work searching for my birth family and in the end, I was exhausted as I went back home to Denmark.

In November 2022 I went back to Korea again. This time I also discovered a lot more. I got a more truthful copy of my case file without revisions and yet again I got in touch with a translator to help me with all the handwritten hangul and hanja (Korean and Sino-Korean script). The case files revealed that my given name was given to me by the director of KSS who became my legal guardian in the absence of birth parents. My birth mother was 24 years old and unmarried at the time she brought me to KSS. Her full name, date of birth and the address where I was born was written in the case file. Next time I go back home to Korea, I will take the next step and search again. It’s like I get a step further every time I go back home to Korea. How I wish that this could have been a lot easier. I know that it could.

My wish and hopes are that the TRC case will show the importance of the rights of adoptees. That adoptees should have the right to have access to their adoption documents and the opportunity to see their own case files according to their own adoption at any time and this should be accepted as well as protected by law.

As it is now, searching for one’s birth family can be really complicated. I’m living proof. It’s like Pandora’s opulent box which the Danish Korean Rights Group has only begun to uncover. There are so many layers to uncover, and it’ll take time, patience, and so much more. But the DKRG has done a great job so far and I believe and hope they will continue to do so in the future. I know that many of us adoptees agree on this. I know that many of us wish for clarification, we wish to know the truth. The truth about our own identity. Our own past. I do myself. No more. No less.

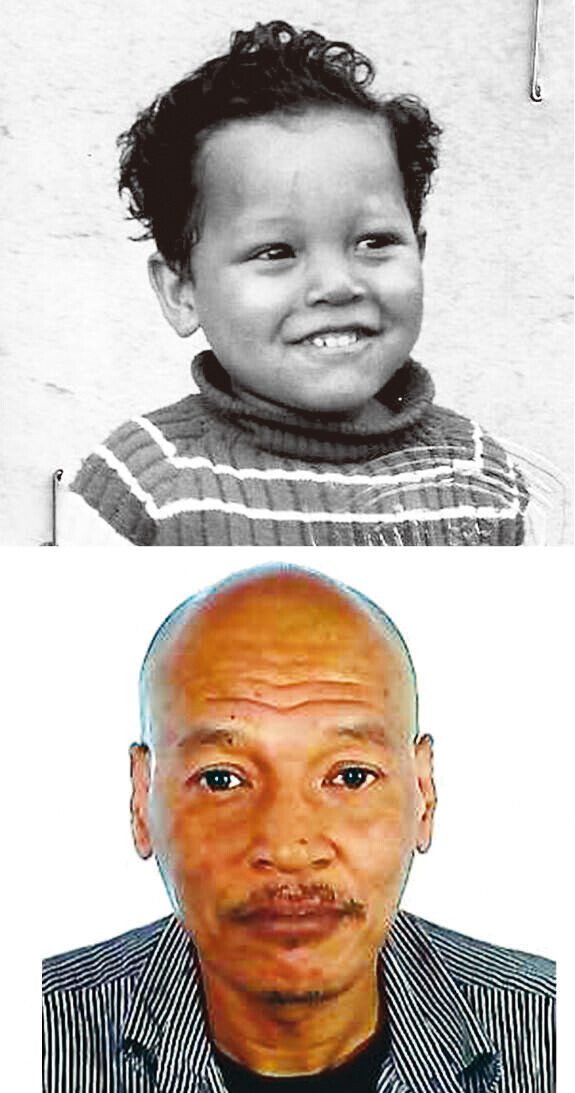

Are the photos in my file even me?

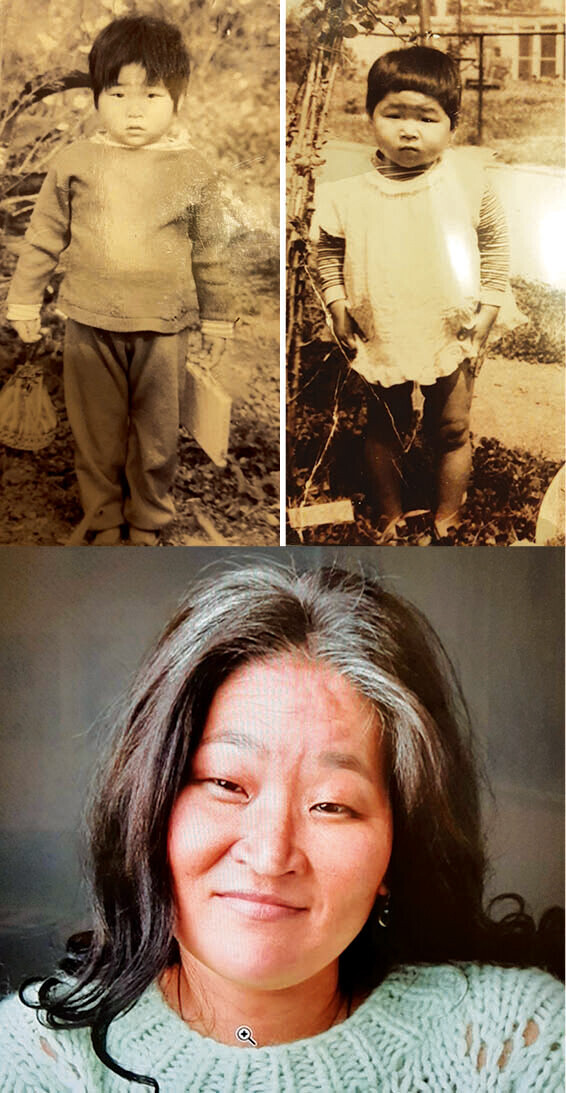

Mie Schlichter. Adopted at 3 years old. Currently 46 years old. Denmark.

My adoption story - Version 1

I arrived in Denmark as a 3-year-old to a Danish nuclear family with two children. They had a desire to make a difference and help an orphaned child. Everything was joyful and I had a safe and happy childhood, although at times I didn’t quite feel like all the others.

My adoption story - Version 2

I only became aware of this story less than a year ago. By chance, I heard about the DKRG request for an investigation into Korean adoptions. I became curious and started digging myself. With the help of many people, I pieced together my adoption story bit by bit. I landed in Denmark on Dec. 16, 1976, at the age of just over 3 years. My adoptive parents had been at the airport three weeks before. They were told I would arrive, but I wasn’t on the plane, and they were sent home again. At the moment, we actually believe that I died on the plane, but we are not sure yet.

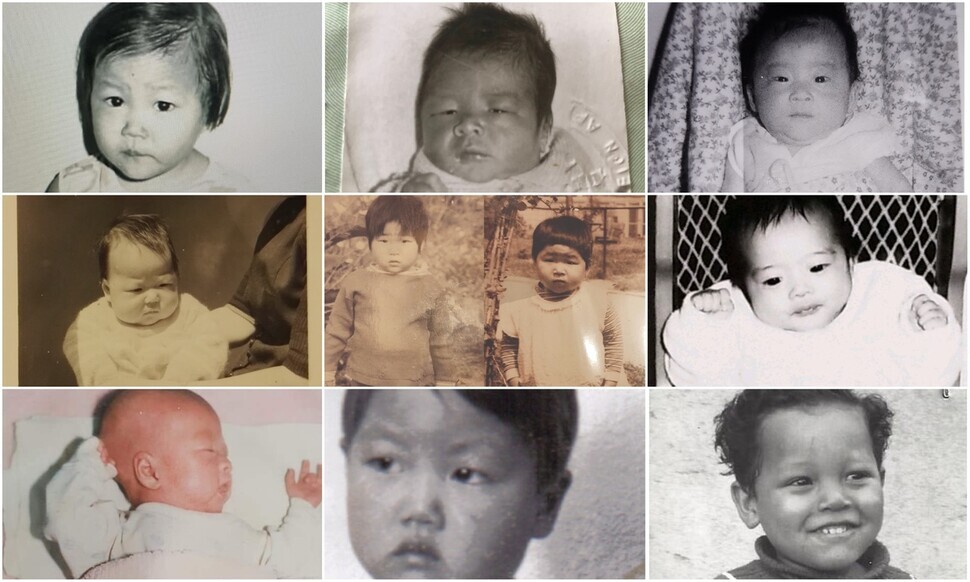

The pictures (above) are of me. These are the pictures I had with me when I arrived in Denmark and met my new parents. What I have found out is that the two pictures may not even be of the same child. Perhaps none of the pictures are of me because many of the documents I have don’t match up. My birthdate has been changed several times and my medical records indicate that I was very seriously ill just before I arrived in Denmark. Or was I? Was it really me who was sick, or was it someone else who unfortunately didn’t make it? If that’s true, then who am I?

My wishes for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s work: I would really like to know who is in the pictures. Is it me? And who is the other person? If I’m a child who was suddenly replaced, what else about my adoption story isn’t correct?

So far, almost nothing fits together. Perhaps I wasn’t actually found on the street? Are there perhaps people in Korea who missed me or still miss me? And what about all the other adoption stories?

Mismatched immigration, adoption records put a question mark on everything

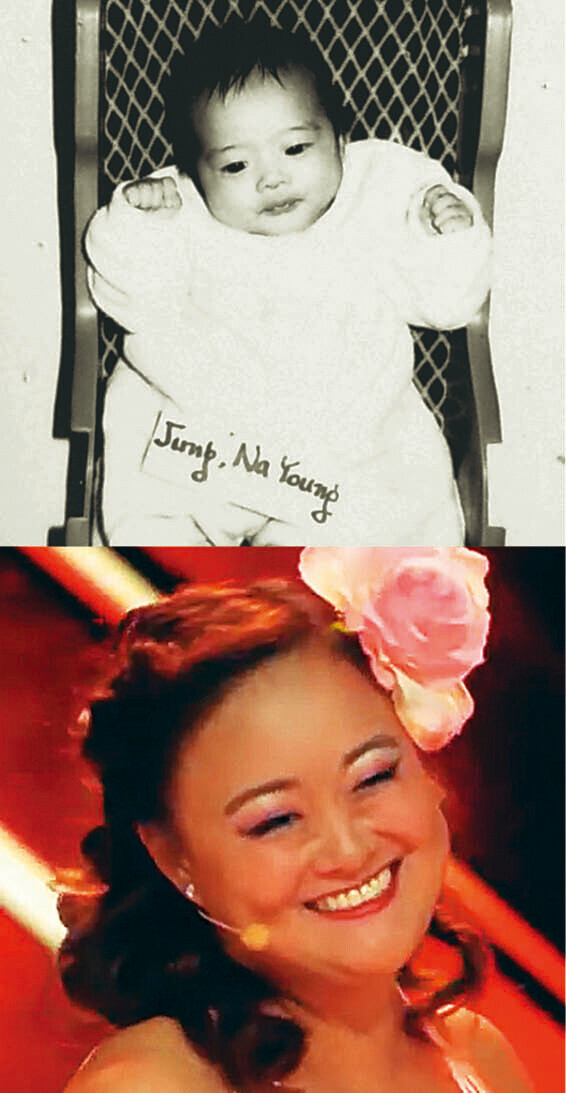

Mary Bowers. Adopted at 5 months old (presumed). Currently 40 or 41 years old. US.

One of my first memories is of my adoptive grandmother decorating a cake. It had three tiers and beautiful buttercream flowers. The sugar sprinkles sparkled like stars. I wanted to live inside that cake, spending my days sledding down hills of snowy, white frosting and hopping through fields of fondant.

Though I would like to imagine that my obsession with cake is rooted in that happy memory, my true connection to this celebratory food isn’t exactly worth celebrating. Between my adoption records, immigration files, and Korean tradition, I have five birthdays every year. At that rate, my life expectancy is somewhere around 433 years. But I have no idea when I was really born. My birthday is marked as “presumed” in the adoption file.

Society tells me I am “lucky” to have been doomed to such a fate. After all, I grew up in the United States with an adoptive family who could feed me birthday cakes like Marie Antoinette before the beheading. There’s not much sympathy for a perceived princess – even one who has been violently severed from her identity, family, and country.

So, I eat my emotions between layers of vanilla frosting. Most of the time, I eat with joy and happiness. But sometimes, each bite comes with grief so deep it doesn’t feel survivable. Regardless of the emotion, it’s always honest. The world has welcomed my unusual truth by inviting me to eat on stages and television sets in places I never could have imagined. Complete strangers have provided profound comfort to my broken heart. I remember their faces, their stories, and the brief moments of connection we’ve shared. Yet, I remain devastatingly invisible to my own family.

On the surface, a confectionary world of wonder may look like a different universe than that of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. They are investigating serious human rights violations ranging from child abuse, to identity laundering, to human trafficking. But the thing about cake, the thing about truth, is that it is easy to decorate even the most bitter, burnt realities and make everything appear to be fine.

I am not okay.

My families are not okay.

My countries are not okay.

Korea’s authoritarian years were violent and tragic. We honor the sacrifices made by the protesters at Gwangju. We celebrate the journalists who were jailed for speaking truth in the fight for democracy. Yet the parents of adoptees who refused or failed to conform to autocratic standards, then were punished with the separation of their families? They continue to be shamed by society.

I would like the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to identify the toxic ingredients of our history, so we can avoid baking them into our future. We cannot keep putting frosting roses upon horrific child abuse, shaming innocent victims, decorating crimes against humanity, and declaring it to be “cake.”

My birth family thought I had died at birth

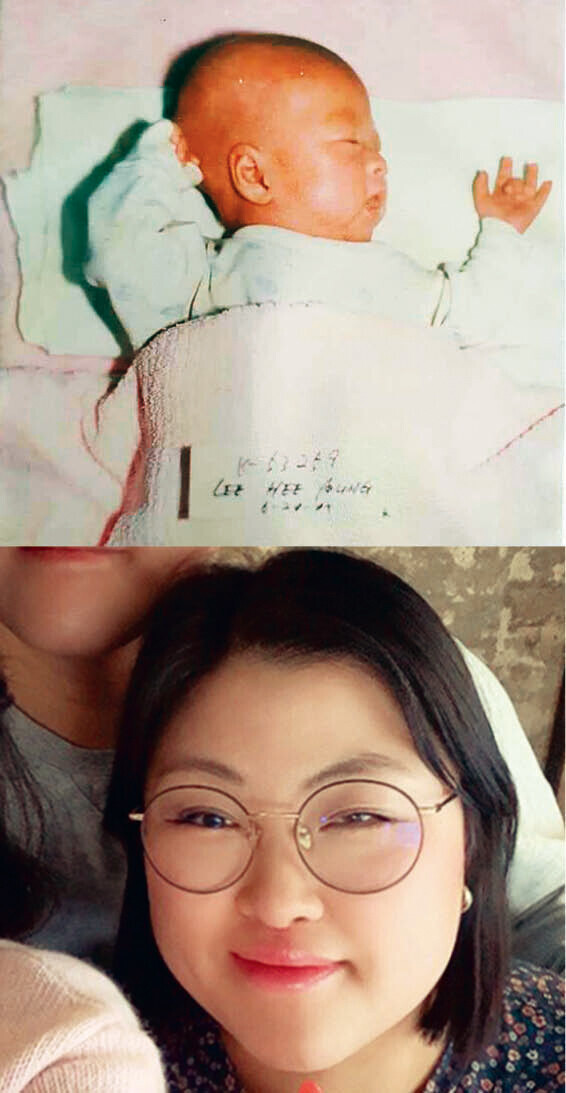

Mia Lee Sørensen. Adopted at 9 months old. Currently 35 years old. Denmark.

My life began around nine months before I came to Denmark, in Gwangju in 1987 when my Korean mom gave birth to me. She went in a rush to the nearest hospital and gave birth to me even though she was 25 weeks pregnant.

It was a true miracle that I survived without any serious damage. But I’m sure I was on a respirator at a hospital for a very long time. No one can tell me for sure.

After that, the doctors told her that I had died at birth and that she should go home. They would take care of it, like I was just some kind of trash going into the garbage. From that day and until I arrived at Copenhagen Airport, Denmark, it’s unsure where I have been, how long and even who made these terrible decisions about my life.

Even my birthday is erased from my Korean family’s memory and there are apparently no records to be found.

I always have thought and believed in the story, that my birth family was poor, didn’t have the means and just wasn’t able to raise me. That’s why they gave me away so I could get a better life. They gave me away so I could live — they gave me away because of love. This is what is written in my adoptive file. And what I believed in for my whole life until last year, when I was reunited with them, and found out that my entire adoption file was made up and fake.

Well, we all got tricked.

My birth family always thought I had died at birth, I always thought my family gave me away because of their unfortunate and poor situation, and my Danish parents always believed that they got me, so they could give me a better life with a lot of love, which my Korean parents weren’t capable of doing.

Although I now have had many of my questions answered and found out that my birth family is without any guilt, I still need to know this (and so are they):

Who did this to me — who did this to my birth family? Where was I while staying in Korea? And who has the right to end and begin a life, the way they did with my life? When is my date of birth, my actual birthday? And how is it possible to be so blinded by money that you can take these inhuman decisions at the cost of a pure and innocent child’s life?

If it happened to me, how many others did this happen to?

In the end, I need justice to be fulfilled. And if it does, then maybe I will be able to live the rest of my life in more peace. This is my hope for the investigation made by the Korean TRC.

All I want is to be with my mother in the time we have left

Simon Hokwerda. Adopted at 4 years old. Currently 57 years old. Netherlands.

I was born Oct. 6, 1966, in Paju County. My mother is Korean, her name is Kim Gwi-ja and my dad was an Afro-American soldier. They met at the bar where my mother had to work, called the UN Club, which must have been in or somewhere near Paju.

Later in 1969, my younger brother was born.

In 1970, I was adopted to the Netherlands because I was a “hapa” (multiracial Asian). I had no chance of going to school, and the safety of our family wasn’t guaranteed by anyone in Korea.

Growing up in the Netherlands I had lots of problems because I had to become someone else.

In 1986 I sent a letter to KSS to ask if they could try to find my mother and brother again. The one person who still remembered me went back to the old address in Paju. But they had changed the whole city and the address didn’t exist anymore. Sadly, he passed away shortly after, and the search stopped. I think he did the search on his own initiative, because it wasn’t followed up by anyone else. There was no Post Adoption Service back in the day.

When I learned from the things that had happened in the camptowns to hapa children like me and their families, I became very angry at Korea and all Koreans. It took a very long time for me to realize that there had always been good and nice people in Korea. Today, I have no anger towards Korea nor Koreans.

I wish that the results of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission will be that Korea and Koreans will come clean with this black chapter in modern history. I hope that the government will take better care of the women who had to work in the army camps. I hope that all the adoption agencies are made to stop adoption to foreign countries. I hope that someone will have the strength to apologize for all the horrors that we adoptees and our biological families still have to go through.

All I want now is to hold my mother and cry with her for the years we’ve lost. This year she turns 79. All I want now is to be with her and share moments in the time we have left. If I ever succeed in finding her.

By Koh Kyoung-tae, senior staff writer

Joint planning and execution by Han Boon-young, co-founder of the DKRG

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 4[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 7[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 8Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 9Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 10Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US