hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Double dilution: Japan, IAEA are watering down the gravity of Fukushima dumping

“Double dilution” might be the best way to describe the recent decisions and rhetoric coming out of the Japanese government. Not only are they trying to dilute irradiated water by discharging it into the sea, but they are also watering down the gravity of the situation by trying to sell the public the idea that this diluted water is safe.

The truth of the matter is that a large amount of radioactive material has seeped out of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant since its meltdown, and this will continue to be the case for the next 30 or so years. Furthermore, TEPCO and the Kishida government are planning to systematically release all that material into the ocean.

What should we call the water that TEPCO intends to release?

Above anything else, it is water contaminated by nuclear materials. This is wastewater contaminated with various radioactive isotopes.

The 2011 meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant damaged four reactors and caused three of them to explode. The failure to cool the reactor cores resulted in the uncontrolled fission of the fuel rods in the cores, which are still melting. The heat melted and punctured the pressure vessel, releasing radioactive materials such as plutonium-239.

TEPCO, the public electric and power corporation that operates Japan’s nuclear plants, has ruled out the possibility that the outermost concrete containment vessel has been breached, but admits that groundwater and rainwater are being contaminated and leaking.

The plant uses groundwater for cooling, meaning that it inevitably produces contaminated water. However, TEPCO has taken various measures to reduce the amount of contaminated water produced, which is about 90 cubic meters per day.

Watering down any contaminate can bring it within safe boundsThe main radionuclide that remains in this contaminated water is tritium.

According to Joo Han-gyu, head of the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, the average concentration of tritium in the contaminated water from Fukushima is 620,000 becquerels per liter, while the standard for drinking water is 10,000 becquerels per liter.

This is exactly why you shouldn’t go straight ahead and glug down a liter of contaminated water from Fukushima, even though Wade Allison, an emeritus professor at Oxford University, claims that you can.

The water is contaminated with more than 60 radionuclides, including cesium-137, strontium-90, and carbon-14.

TEPCO is in the process of treating the contaminated water to remove these nuclides, which is why it calls the water it plans to release “treated water.”

First, cesium and strontium are routinely removed, and then 62 radionuclides are removed using a multi-nuclide filtration process called the Advanced Liquid Processing System, or “ALPS” for short.

However, as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) acknowledged in its report, ALPS does not completely remove all nuclides, so a small number of nuclides remain in the treated water.

ALPS fails to remove tritium from the contaminated water. High concentrations of carbon-14 also remain in the treated water, as TEPCO has reluctantly admitted.

But it’s not the water that remains after ALPS filtration that the Japanese government has decided to discharge into the sea. This “treated water” will be diluted with seawater, which will then be released as “diluted water.”

Why go ahead and dilute water that’s already been treated? Because the radionuclides in the treated water exceed Japan’s standards. Safety standards regulate the percentage of radioactive material remaining in the water, not the total amount, meaning that TEPCO meets that standard by adding uncontaminated water.

Like I said, it’s literally diluting. Any contaminant can be doused with water at will to bring the concentration down below the safety standard, so it’s hardly a measure that prioritizes environmental and human safety.

There is no way to check that the diluted water is fully compliant with safety standards.

While TEPCO released the results of its radionuclide measurement, those results only covered 10 of the 62 radionuclides in the contaminated water. Without any data about the other 52 radionuclides, there’s no way to check how much of them remain in the diluted water.

There are also many aspects of TEPCO’s data that seem to defy scientific explanation. For example, the concentration ratios of cesium-137 and strontium-90 varied by a factor of up to 16,000, even though they have the same half-life.

Even more importantly, TEPCO didn’t measure the change in concentrations over time or the difference in concentrations before and after ALPS treatment. By refusing to disclose such basic data, TEPCO has made it impossible to confirm how much of the radionuclides are actually being removed by ALPS.

The IAEA admits as much in the report it released on July 4, which notes that the efficiency of ALPS and other equipment installed to filter radionuclides from the contaminated water at the Fukushima nuclear plant is not considered anywhere in the report.

The IAEA justifies this on the grounds that the radionuclide concentration in the diluted water can be measured to confirm its safety, but that inevitably casts doubt on the effectiveness of the work to remove radionuclides. How do we know that TEPCO didn’t merely pretend to remove the radionuclides from water it meant to ultimately dump after dilution?

Preordained conclusion

So why is the IAEA backing up Japan’s plan? First of all, the organization’s raison d’être is to support and encourage the nonmilitary use of nuclear power. The IAEA initially categorized Fukushima as a Level 5 accident and didn’t confirm it as a Level 7 accident (the worst level) until the Japanese government acknowledged it as such.

In its second inspection report of the Fukushima nuclear power plant in 2013, the IAEA said that a sustainable solution should be found for the contaminated water and stressed that all options should be on the table, including the possibility of resuming the controlled discharge of the water into the ocean. In short, the IAEA had made this recommendation even before the Japanese government set up a task force about treating the contaminated water.

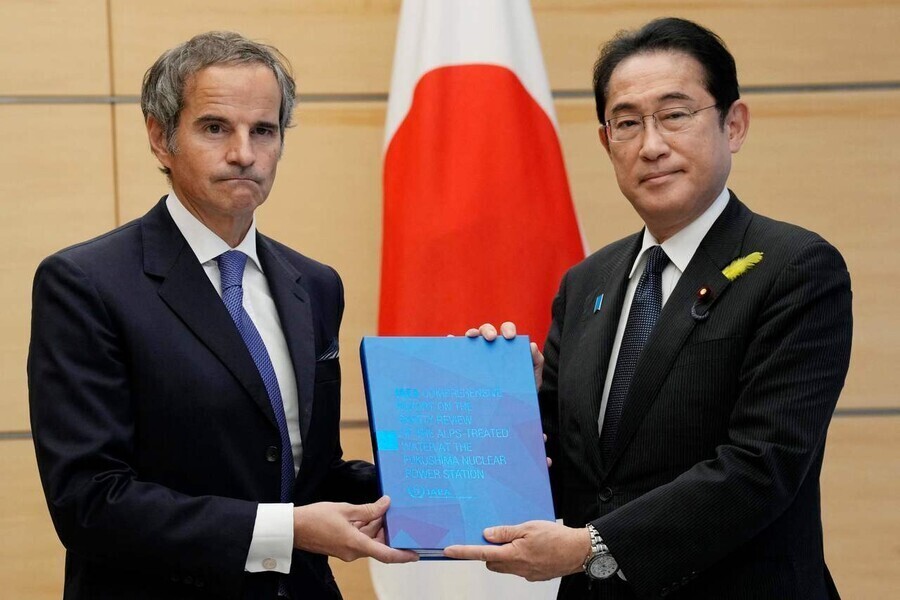

So it was only natural when the IAEA signed “terms of reference” with the Japanese government on July 8, 2021, about the scope of support that the IAEA could provide the Japanese government in reviewing the safety of contaminated water treated by ALPS at the Fukushima nuclear power plant. While announcing this development, the IAEA confirmed that it and Japan had been “cooperating extensively over the past decade to deal with the aftermath of the Fukushima Daiichi accident.” The IAEA also quoted Director General Rafael Grossi as saying that “Japan’s chosen disposal method is both technically feasible and in line with international practice.”

In short, the IAEA’s decision had already been made two years before the fact.

The “IAEA Comprehensive Report on the Safety Review of the ALPS-Treated Water at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station” that was released on July 4 was composed according to the IAEA’s terms of reference with Japan. In short, the report was the product of a service contract aimed at supporting Japan that was signed three months after the Japanese government announced its plan to discharge the contaminated water into the ocean.

Seeing as that contract was not designed to review the legitimacy of a plan prior to establishment, the Japanese government never had any intention of reviewing the plan’s safety from a third-party perspective.

The service contract lacked transparency, too. No information has been disclosed about the terms of the contract or about the cost of the project. Given the opaque contract and the foreordained conclusion, the IAEA’s support for Japan’s treatment of the contaminated water is losing credibility on an international level.

By Suh Jae-jung, professor of political science and international relations at the International Christian University in Tokyo

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0630/9717197068967684.jpg) [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

[Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated![[Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0628/7617195640940814.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

[Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

- [Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?

- [Editorial] Seoul failed to use diplomacy with Moscow — now it’s resorting to threats

- [Column] Balloons, drones, wiretapping… Yongsan’s got it all!

- [Editorial] It’s time for us all to rethink our approach to North Korea

- [Column] Why empty gestures matter more than ever

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- 2Dreams of a better life brought them to Korea — then a tragic fire tore them apart

- 3S. Korea joins US, Japan for first multi-domain drills at a time of escalating tensions

- 4Yoon echoed conspiracy theories about Itaewon disaster, former National Assembly speaker says

- 5Moscow tells Seoul to rethink ‘confrontational course’

- 6[Editorial] It’s time for us all to rethink our approach to North Korea

- 7[Column] Balloons, drones, wiretapping… Yongsan’s got it all!

- 8CIA record confirms US ‘completely destroyed’ Seoul’s Haebangchon in 1950 bombardment

- 9[Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- 10[Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem