hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Auto rally for Korean unification travels 18,000km from Moscow to southern end of Korean Peninsula

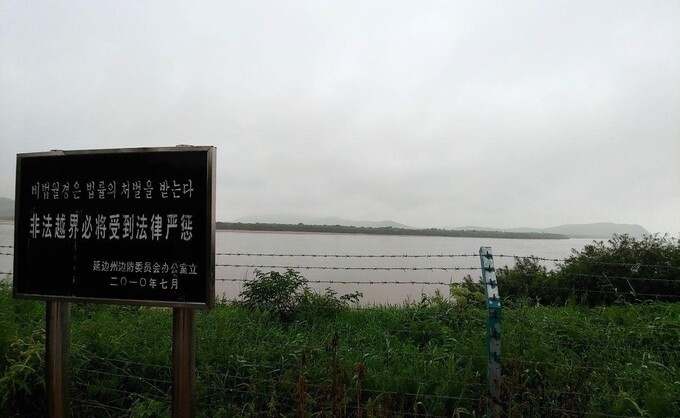

They had hoped to cross the Duman (Tumen) River and continue on through Pyongyang to Haenam Ttanggut Village (“Land’s End”) in Haenam County, South Jeolla Province. But the railroad linking Khasan in Russia’s Primorsky Krai – the route of entry to the Korean Peninsula – with Rajin in North Korea never ended up being opened. As they looked out onto North Korean territory after a 16,500km journey from Moscow, members from the auto rally to commemorate the centennial of the March 1 Independence Movement and wish for Korea’s peaceful reunification truly sensed the reality of Korea’s division. With peace having yet to establish itself between South and North, the Korean Peninsula was effectively an island. The Hankyoreh followed along for the final journey of the rally, which was organized by the group PeaceAsia.

“The present situation is not one in which a rally can take place.”

With the final word from North Korea, the slender strand of hope turned to despair. The sad news came three days after reports that the North had launched a missile to protest joint South Korea-US military exercises. Rally members had difficulty accepting that the path had been closed to them with just 1,300km left to their destination. Some Kareisky (a term used to refer to ethnic Koreans from the former Soviet Union) participants packed their bags and returned to Russia, concluding there was “no point in paying only a half-visit to the homeland.”

As a last resort, 23 rally members boarded a boat on Aug. 14 traveling from Vladivostok to Donghae, Gangwon Province. On board the vessel at the same time that they should have been heading to Pyongyang, the members appeared glum. The boat was swaying heavily from the effects of Typhoon Krosa, the 10th such storm of the season. “It’s just too bad. This is the reality [of division],” said Oleg Kim, a 50-year-old third-generation Kareisky, as he looked out over the shoreline toward North Korea. By land, the distance could be covered in six hours; it was only after 23 hours of travel by boat that they arrived on land in South Korea.

On Aug. 17, the rally’s vehicles traveled along a winding road, the misty landscape of the Soyang River Dam beside them. To the Kareiskys and overseas Koreans who were the rally’s main participants, it was the homeland vista they had spent a lifetime dreaming of. Their first stop was the House of Sharing in Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province, home to comfort women survivors drafted into sexual slavery for the Japanese military. Only 20 of the 240 comfort women survivors registered with the government remain alive today; six of them live at the House of Sharing.

The encounter between the Kareiskys and the elderly survivors was warm. Two of them, both with the name Lee Ok-seon, cheerily greeted their compatriots visiting their homeland. All of them shared the experience of being victims of the painful history of Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea. Mere teenagers at the time during the height of the Pacific War in the early 1940s, the two survivors were taken to China from their respective homes in Daegu and Busan and subjected to torturous experiences; the Kareiskys, who lived in Russia’s region, were forcibly resettled in the wastelands of Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan by the Joseph Stalin government slightly earlier in 1937 after being falsely accused of spying for the Japanese military. The aim of their journey – which took them across Central Asia through the Independence Movement’s sacred site of Harbin and on through Primorsky Krai before arriving at the Korean Peninsula – was to look back of the harrowing history of the Japanese occupation.

Greeting Lee Ok-seon from Daegu, rally leader Ernest Kim, a 60-year-old second-generation Kareisky, said, “I came here from Russia. I very much wanted to meet you.” Lee clasped his hands and said, “It must have been difficult traveling such a long way.” Wishing the elderly survivors good health in their halting Korean, the Kareiskys offered a deep bow. Rally members laughed when Lee urge them to “go back and make a lot of money.”

“They were worried about the women’s health and were relieved to see they were well,” explained Yu Eun-jae, the 58-year-old director of the Dongdaemun Kareisky Korean School in Seoul, who also took part in the rally. “We came to offer comfort, but we ended up drawing more strength from them.”

The same day, the rally members headed to Ansan, Gyeonggi Province, to meet with family members of victims of the Sewol ferry sinking. For these participants living in different parts of Central Asia, the Sewol tragedy was a painful chapter of their homeland’s history in need of remembering.

The rally members began tearing up almost from the moment they met Yoon Gyeong-hee – whose daughter Si-yeon was among the tragedy’s victims – at Hwarang Park, the future site of the “April 16 Sewol life safety park.”

The group was told how Si-yeon’s body had been recovered six days after the accident, her mobile phone still clutched in her hand, and how her bereaved family members were still attending protests, demanding a thorough investigation of the disaster. “We mustn’t let such a painful event happen again in Korea, or anywhere else in the world for that matter,” said 61-year-old Larissa Chang, a second-generation Kareisky.

Rally members promised the bereaved family members that they would wear the yellow ribbons that symbolize solidarity with the Sewol victims until they completed their trip to South Korea and returned to Moscow. After spending a moment of respectful silence before the funeral portraits of the 304 victims, the rally members got back into their cars.

The vehicles headed toward Ttanggut Village in Haenam County, the rally’s final destination. Along the way, they stopped at Independence Hall of Korea, in Cheonan — which recently hosted a ceremony marking the 74th anniversary of Korea’s liberation from the Japanese occupation — and at the Presidential Archives in Sejong. At these sites, rally members pondered painful episodes in Korea’s history, including the military dictatorship and the impeachment of former president Park Geun-hye.

Fifty-one-year-old Leonid Choi, a third-generation Kareisky, spoke with pride of the historic achievements of the Korean people, mentioning the independence movement during the Japanese colonial occupation, the mass protests that brought down the dictatorship of Syngman Rhee in April 1960, and the candlelit rallies that ultimately led to the impeachment of Park Geun-hye in 2017.

When the rally members neared the cemetery where the victims of the Gwangju Massacre are laid at rest, they took a detour that put a damper on their excitement about only being 130km away from the end of their trip. After paying their respects at the cemetery, they paused in front of the memorials to Yun Sang-won, an activist during the Gwangju Democratization Movement who was killed, and Park Gi-sun, a labor activist who lost his life from exposure to gas in 1978. Together, the rally members sang “March for the Beloved,” a song made tragic by its performance at Yun and Park’s “spiritual wedding,” a symbolic ceremony held after their death.

This song was familiar to the members, since it had been widely sung at protests in several Asian countries, including Taiwan, the Philippines, and, most recently, Hong Kong. This song, which crystallizes a painful period in history, helped to unify Koreans who came from all corners of the diaspora.

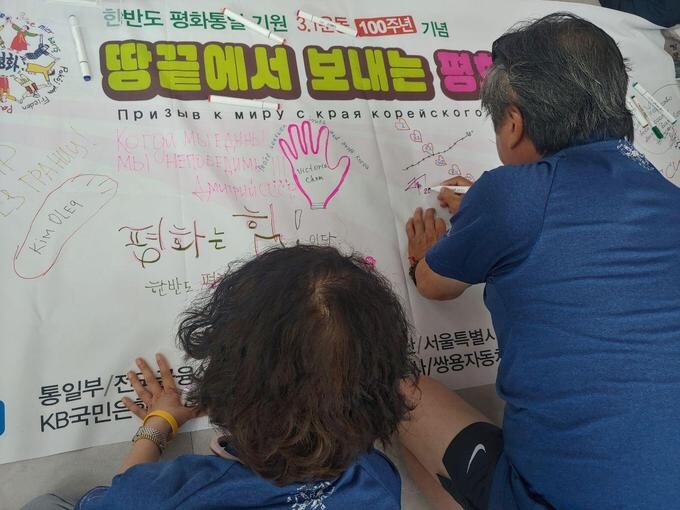

On Aug. 20, the rally members arrived at Ttanggut village, the southernmost village on the Korean Peninsula. This was the final moment in their great journey, which had begun in Moscow and continued through Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, and China, finally bringing them to South Korea. This was the first time I’d seen a broad smile flash across the faces of the Kareisky, after the troubled expressions elicited by the news that the road through North Korea had been closed and by their encounters with the comfort women, the Sewol tragedy, and the Gwangju Massacre.

“This was a record-setting rally that crossed national borders on eight occasions and covered 18,000km on land and sea in 42 days. I hope this rally will be remembered as an attempt to accelerate peaceful reunification and to bring comfort to the hurting on the Korean Peninsula,” said Jang Sang-rak, the chair of Peace Asia’s executive committee for the rally.

Standing in front of a stone memorial that symbolizes Ttanggut village, the Kareisky and other rally members looked north as they raised a hearty cheer for Korea and for its peaceful reunification. On Aug. 25, they will be boarding a ship at Donghae bound for Vladivostok. From there, they will return to Moscow by land, through Russian territory.

By Ock Kee-won, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis![[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track? [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/1617144616798244.jpg) [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

Most viewed articles

- 1Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors

- 2[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 3Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 4[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 5Value of Korean won down 7.3% in 2024, a steeper plunge than during 2008 crisis

- 6After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 7Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 8First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 9[Editorial] Japan’s removal of forced labor memorial tramples on remembrance, reflection and friends

- 10Strong dollar isn’t all that’s pushing won exchange rate into to 1,400 range