hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

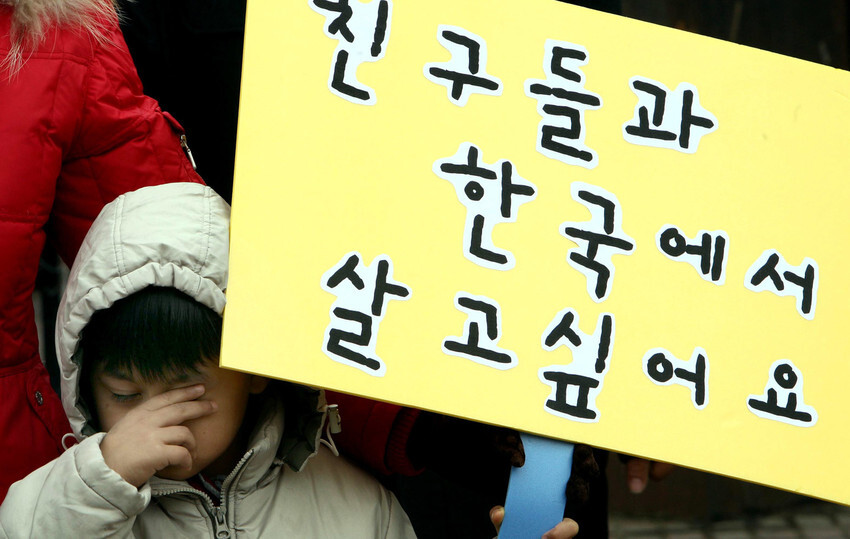

“Shadow children” of undocumented migrants fall through cracks of COVID-19 response

Eight-year-old Habib (pseudonym) is a “shadow child.” Born in South Korea in 2013, he speaks only Korean and eats only Korean food. But his birth was never registered, and he cannot receive an alien registration card. His father Nathan (also a pseudonym) applied for refugee status when he arrived in South Korea 10 years ago from Kenya, but his status as an undocumented resident means that his life is still insecure. Under the South Korean system, children born to undocumented residents and couples who have applied for refugee status exist outside the law.

On May 5 -- the Children’s Day holiday and the day before the novel coronavirus response system transitioned from “social distancing” to “everyday disease prevention” -- amusement parks all over South Korea were thronged with small children and their parents. But Habib spent the day unable to leave his home in Dongducheon, Gyeonggi Province.

Obviously, Habib does not qualify for health insurance either. Last month, he suddenly came down with a cough and fever, but he was unable to go to the hospital.

“We’re worried about being arrested, and the hospital fees are more than we can afford, so I haven’t been able to take my son to the hospital even with the coronavirus outbreak going on,” Nathan explained.

“All we’ve been able to do is weather the storm taking cold medication that people have helped us to get from the pharmacy,” he added.

Article 24 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which the South Korean government adopted in 1991, stipulates health rights for all children, while Article 4 of South Korea’s own Child Welfare Act states that children must be able to grow up without “experiencing any kind of discrimination on the grounds of their or their parent’s gender, age, religion, social status, property, disability, birthplace, race, etc.”

But in practice, the agreement is not effectively observed.

As many as 10,000 or more undocumented migrants’ children like Habib are currently living in the “shadows” in South Korea. The results of a survey of “children residing in South Korea” published in November 2018 by the Korean Association for Public Administration estimated the number of undocumented migrants’ children as ranging from 5,200 to as many as 13,000. In May 2019, the government announced plans to institute a “childbirth notification system” under which healthcare professionals involved in childbirths would be responsible for reporting them -- but the measure ran into objections from the healthcare workers who would be taking on the new legal responsibility. This has left no apparent practical alternatives for protecting the rights of undocumented migrants’ children.

“Any other year, civic and social groups would be joining forces on Children’s Day to organize small-scale events and give gifts to undocumented migrants’ children. Unfortunately, most of the events this year have been cancelled because of the coronavirus,” explained Seok Won-jeong, director of the Seongdong Global Migrant Center.

“Undocumented migrants’ children and their family members have been completely excluded from the coronavirus prevention measures,” Seok added. “It’s important to establish measures to guarantee their health, if only for the sake of South Korean society as a whole.”

By Lee Jae-ho and Kang Jae-gu, staff reporters

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 3[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 4[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner t

- 5Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 6[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

- 7‘Shot, stabbed, piled on a truck’: Mystery of missing dead at Gwangju Prison

- 8China calls US tariffs ‘madness,’ warns of full-on trade conflict

- 9Seoul government announces comprehensive measures to prevent lonely deaths

- 10Records show how America stood back and watched as Gwangju was martyred for Korean democracy