hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] Can S. Korea-Japan relations get back on track?

On June 29, the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) Dispute Settlement Body held the first meeting to initiate a dispute settlement process about the export controls that Japan imposed on South Korea in July 2019. The meeting, held at Korea’s request, adjourned inconclusively, with Japan staunchly refusing to set up the panel that represents the first stage of the process. Japan is stubbornly stonewalling the process even though the panel’s establishment cannot be stopped without the unanimous agreement of member countries.

Korea and Japan are also bickering once again over a number of sensitive issues, including the recent controversy over historical distortions connected with an exhibition about Hashima Island (also known as Battleship Island), which has been registered as a UNESCO world heritage site. The two countries appear to have returned to their brawl, ending a brief truce that began during the height of East Asia’s COVID-19 pandemic in early March.

July 1 marks one year since Korea-Japan relations turned rocky after Japan imposed export controls on hydrogen fluoride and other materials that are essential for Korea’s manufacture of semiconductors. Yet the two countries’ relations still haven’t rebounded from what represents a historical low point. Japan’s measures were regarded by Koreans as “economic aggression,” prompting a nationwide boycott against Japanese products and travel to Japan. Then the South Korean government announced that it would be scrapping its General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA) with Japan, shifting the point of contention from the economy to national security. A rupture was avoided when Korean backed down, opting to extend the agreement, but there are still no indications that relations will improve.

The consensus among experts is that repairing and normalizing Korea-Japan relations will require finding an amicable compromise to the South Korean Supreme Court decision that is the ultimate cause of all these disputes; namely, the decision in which the court ordered that Korean victims of forced labor during Japan’s colonial occupation of Korea should be compensated. But the prospects for such a compromise are grim, with both sides demanding decisive concessions from the other while reiterating that the current course spells mutual destruction.

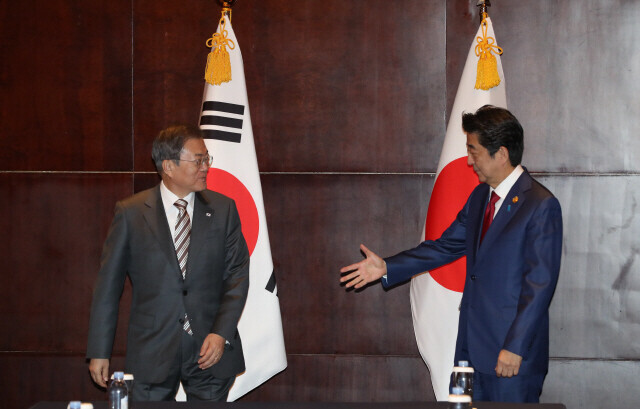

Japan insists on maintaining 1965 claims agreementThe deadlock in the Korea-Japan negotiations was dramatically illustrated by the crossfire between the two countries’ leaders early this year. During a New Year’s press conference on Jan. 14, South Korean President Moon Jae-in underlined his commitment to finding a solution through dialogue and called on the two sides to “put their heads together and gather wisdom.” The response made by Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe six days later was callous to the extreme: “Promises between states must be kept.” Abe was demanding that Korea abide by a 1965 claims agreement in which the two countries declared that all outstanding claims were “completely and finally resolved.” “After making its first offer in June 2019, the Korean government has sweetened the pot several times. But Japan’s obstinate refusals means that nothing can be done,” said Yang Gi-ho, a professor at Sungkonghoe University.

The Blue House has also remained flexible in diplomatic deliberations, only insisting on the minimum standard that the payments made to the plaintiffs must come from the Japanese companies. But Korean negotiators have reportedly been taken aback by Japan’s hard line.

“Japan is committed to defending the ‘1965 System,’ the foundation of its contemporary relations with Korea. The moment that the money made by liquidating assets belonging to Japanese companies is put in the hands of the plaintiffs, the claims agreement would be nullified,” said Hideki Okuzono, a professor at the University of Shizuoka.

In short, Korea is seeking a solution inside the framework of the Supreme Court’s decision, while Japan is desperately defending the 1965 System, in what amounts to a fierce struggle with no obvious compromise available.

While the Korean government doesn’t want another run-in with Japan, its position is that such a run-in is unavoidable. The government and the ruling Democratic Party are making preparations to minimize the shock of additional retaliatory measures that Japan could take if the plaintiffs proceed with liquidating the assets in the second half of this year.

“By firmly standing up to Japan’s sneak attack a year ago, we managed to turn evil into good,” Moon said during a meeting with his aides and senior secretaries on June 29. In March 2019, Japanese Deputy Prime Minister Taro Aso said that the measures available to Japan include tariffs, halting remittances, and suspending visa issuance.

Japan’s consistent roadblocks in inter-Korean peace processKorea and Japan are shifting from a dispute over historical matters to a structural dispute over vital issues that reflect the two countries’ irreconcilable differences over the future of East Asia, which is entering a new Cold War. Since 2018, Japan has thrown up roadblocks at every crucial turning point in the North Korea-US nuclear talks and in the South Korean government’s efforts to improve relations with the North, with Koreans’ fate hanging in the balance. More recently, Japan even opposed an American proposal to include South Korea in an expanded G7 summit, taking issue with South Korea’s stance on China and North Korea.

The conflict over the Supreme Court’s decision during these past two years has also shown that Korean and Japan’s strategic interests — which were once assumed to be headed in the same direction — are in fact quite different. Itsunori Onodera, who has twice served as defense minister in Abe’s cabinet, has said that Japan should “respectfully ignore” Korea rather than working to improve relations with it.

Korea’s dismissal of Japan would only strengthen US-Japan relationsBut other observers say it’s extremely dangerous for Korea to disregard its relations with Japan. That would allow Japan to draw upon its alliance with the US — which has priority over the South Korea-US alliance — to repeatedly interfere with South Korea’s advancement of the Korean Peninsula Peace Process.

“I don’t think that the [South Korean] government has ever properly discussed the Korean Peninsula Peace Process with Japan. Difficult times demand leaders to exercise wisdom and make tough calls,” said Cho Jin-gu, a professor at the Institute for Far Eastern Studies at Kyungnam University.

By Gil Yun-hyung, staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 3AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 4[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 5Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 6Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 7Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 8Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 9The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 10Yoon says collective action by doctors ‘shakes foundations of liberty and rule of law’