hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Why was Korea divided after World War II instead of Japan?

How did Korea come to be divided after World War II, rather than Japan, the country that was defeated in that war? The question is one that pretty much any Korean will have asked at some point. The division is so unfair, especially considering that it began on Aug. 15, the very day on which Koreans celebrate their liberation from Japan’s colonial occupation. While Koreans were once again free to speak and write in their own language, it’s unfair that millions of families were separated, never to see each other again, and that the country became a global battlefield. It’s also unfair that the strife and tension of division persist until the present day. Are these ironies just a coincidence? Recent research has drawn upon declassified documents to shed light on how this came about.

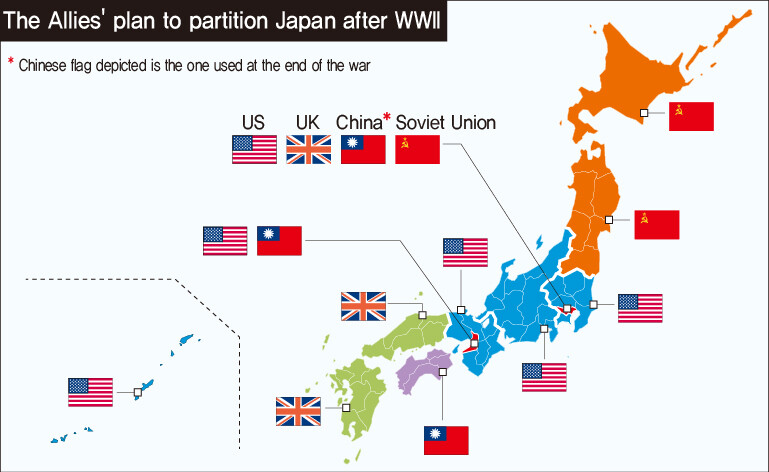

After their victory in World War II, the Allies decided to divide Japan into separate occupation zones, just as they had done with Germany, the other major Axis power. The occupation of Germany began in June 1945, and Japan was the next in line. The US, Great Britain, China, and the Soviet Union agreed on the division at the Potsdam Conference in July. Under the occupation plan that was discussed, Kanto and Kansai were to be occupied by the US, Hokkaido and Tohoku by the Soviet Union, Kyushu and Chugoku by the UK, and Shikoku by China, while Tokyo was to be split four ways, just as had happened to Berlin. On Aug. 13, the US State Department drew up a plan for the forces required for each occupation zone.

So why was the plan to carve up Japan not carried out, and Korea divided instead? What happened over those final days? Why did the Japanese, who had sworn to fight to the last man, so hurriedly surrender on Aug. 15? The orthodox view until recently has been that the Japanese were forced to surrender by the dropping of the atomic bombs. But according to Japanese-American professor Tsuyoshi Hasegawa, the Soviets’ entrance into the war was more decisive than the bomb. Hasegawa said that the Japanese surrendered to the US to protect the imperial system and to avoid a Soviet-involved partition of the country. The idea that the atomic bomb forced the Japanese to surrender provided support for the US’ unilateral occupation of the Japanese home islands. (Hasegawa’s argument can be found in his book “Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan.”)

From another angle, Japanese professor Yukiko Koshiro believes that the Japanese military leadership sought to center the American and Soviet standoff on the Chinese mainland, Manchuria, and the Korean Peninsula, rather than the Japanese home islands. Their goal was to create conditions favorable for Japan’s postwar recovery. The Japanese military had even identified the 38th parallel on the Korean peninsula as being one of the likely points of confrontation between the Americans and the Soviets. When the Soviets began their offensive on Aug. 9, they immediately struck into Manchuria and the southern half of Sakhalin island and seized Unggi in North Hamgyong Province within a single day. Japan communicated its intention to surrender the very next day, on Aug. 10. That same evening, Col. Dean Rusk proposed that the 38th parallel separate two spheres of control on the Korean Peninsula. It was only a matter of time before the Soviets made an amphibious landing on Hokkaido. On Aug. 15, the Japanese emperor announced the end of the war (rather than surrendering or acknowledging Japan’s defeat). This swift surrender enabled Japan to avoid what it had feared the most; namely, Soviet involvement in the partition and occupation of the Japanese home islands.

Japan’s late surrender brought Soviets into the war and precipitated atom bomb catastrophesBut paradoxically, the surrender came far too late, dragging the Soviet Union into East Asia and precipitating the human catastrophe of the atomic bomb. When the Allies were discussing the Soviet Union’s participation in the war against Japan at Yalta in February 1945, former Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe argued that Japan’s defeat was inevitable. If Japan wanted to avoid a communist revolution and preserve the emperor following the war, Konoe said, it ought to quickly negotiate with the British and the Americans to bring the war to an end. But Emperor Hirohito thought a harsh blow should be struck against the enemy first to gain the upper hand in the armistice negotiations. That was what led to the Battle of Okinawa in April.

Japan’s objective in Battle of Okinawa was not victory but maximum bloodshedThe battle proved to be one of the bloodiest of the war. The Japanese goal at Okinawa was not to win but rather to cause so much bloodshed that the US would offer more lenient terms of surrender. Bloodshed was demanded not only from the Japanese troops fighting the battle but also from all the civilians on the island. Kamikaze units were deployed to launch suicide attacks. The island was described as a “breakwater” defending the Japanese home islands and as a “sacrificial stone.” And the fighting was horrific. In addition to the large number of casualties on both sides, 120,000 of the 460,000 residents of the island were killed. An estimated 10,000 Korean workers and comfort women who’d been forcibly conscripted lost their lives, too.

The reckless and brutal bloodletting that the US military confronted in this battle accelerated the Soviet Union’s entry into the war, as well as the Americans’ development of the atomic bomb. Once the bomb was finished, the US dropped it on two cities inhabited by hundreds of thousands of people in an attempt to bring the war to a close. By brandishing the power of its newly developed weapon, the US also sought to consolidate its postwar hegemony. And the Soviet Union, by pulling forward the date of its invasion, hoped to seize its share of Japanese territory. As Japan delayed its surrender to preserve the imperial system and as the Allies maneuvered for their own strategic advantage in East Asia, millions of lives were lost and the Korean people were doomed to division.

Upon hearing of Japan’s surrender, Korean independence activist and politician Kim Gu (1876 – 1949), lamented the peculiar timing. Liberation was not an unalloyed joy for the leader of Korea’s government in exile, who had witnessed the brutality of geopolitics during the long civil war between the Chinese nationalists and communists. The division that accompanied liberation has now lasted for 75 years, and Koreans are still afflicted by inter-Korean conflict and the fear of war. Despite the pain of division, we have built the “strength of culture” that Kim had so fervently hoped for. Geopolitics once again threaten to make Korea the front line of a clash between the superpowers of the US and China. The time has come for us to seek the wisdom of an independent foreign policy.

By Chung Byung-ho, professor of anthropology at Hanyang University

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 2[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 3Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 4Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 5[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 6[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 7Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 8Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 9[Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- 10Video evidence surfaces showing Korean comfort women were massacred by Japanese military