hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Dispelling the myth of Cuban doctors as “slaves in white gowns”

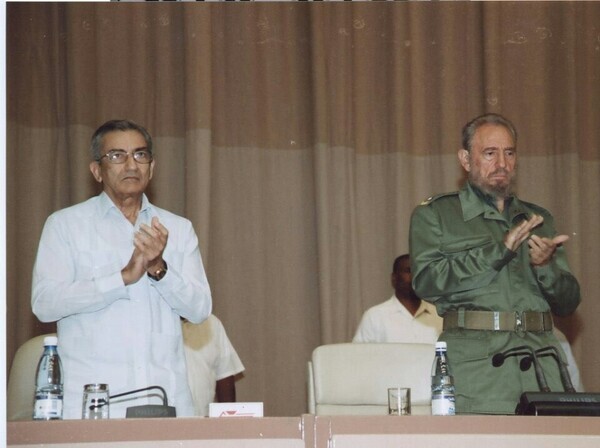

“Fidel [Castro] once said, ‘Cuba does not bomb our neighbors; we send doctors.’ But recently one South Korean news outlet published an article out of nowhere with the sensationalistic title, ‘White Gown Slaves: Another Name for Health Services in Cuba.’ I see this as biased and distorted reporting, which overtly shows the political aim of supporting a physicians’ strike in protest of policies to bolster health services by citing an overseas example where it’s difficult to verify the facts or for the people involved to respond directly. That’s why I felt like I needed to do something at least.”

Jeong I-na, 43, seemed quite earnest. On Sept. 7, the former professor at the Busan University of Foreign Studies published a rebuttal column titled “Eternally Unhappy about Public Health Services: The Truth about the Chosun Ilbo’s Unseemly Article” (http://thetomorrow.kr/archives/12784) on the website of The Tomorrow, a group of intellectuals seeking an alternative society. As a doctor of social anthropology specializing in Central and South America and a first-year premed at the Medical University of Havana, she is better acquainted than anyone with the reality of healthcare in Cuba. The Hankyoreh sat down with Jeong -- who is currently staying in South Korea since returning in July -- to hear what led her to quit her job as a professor and become the “oldest medical student” in Cuba in her 40s.

“The article was filled with falsehoods, from the parts about female doctors dispatched to Guatemala being forced into prostitution to the ridiculous claims about Cuban physicians being required to perform overseas medical services or about people having to spend years in jail if they want to give up their medical license,” she said.

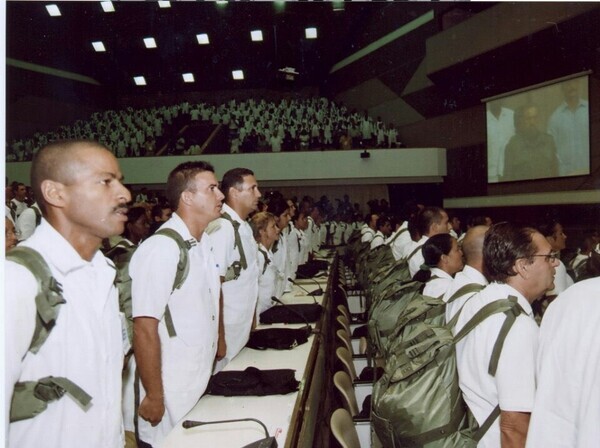

“Cuba’s Henry Reeve International Medical Brigade, which [the Chosun Ilbo] made out to be ‘slaves in white gowns,’ was awarded the 2017 Dr. Lee Jong-wook Memorial Prize for Public Health in honor of South Korea’s first World Health Organization (WHO) director-general Lee Jong-wook for its efforts in providing emergency medical assistance to millions of disaster and disease-afflicted people around the world since its establishment in 2005,” she noted.

Jeong also shared some of the things she had witnessed for herself in Havana prior to her return. “We watched a broadcast of 52 doctors returning home safely after finishing two months of duties in Italy, where they had been dispatched at the Italians’ request, and the pride on their faces was obvious,” she said, adding that Cuba “has sent physicians to over 30 different countries for COVID-19 control efforts.”

Indeed, Cuba’s efforts to combat the virus have been cited alongside South Korea’s as model examples. As of July 3, the cumulative number of confirmed cases of the virus in Cuba was under 2,400, with 86 total deaths. The respective totals were 1/27th of those in neighboring Mexico and 1/70th of those in Brazil.

“Early on the coronavirus pandemic, the Cuban authorities’ first step was to initiate joint activities focusing on local communities. It sent all physicians and medical students to different regions and organized a special dedicated team of healthcare workers to investigate conditions for senior citizens and segments vulnerable to infectious disease. The aim of these swift measures was to ensure that everyone enjoyed an equal right to survive. I think Cuba’s decision was the right one.”

Jeong’s belief stems in part from her own experiences with the benefits of Cuba’s international medical brigade. “As a high school student, I enjoyed Spanish and dreamed of becoming an interpreter. So I studied overseas at a private university in Guadalajara,” she explained. “After that, I attended the Seoul National University graduate school with a focus on Central and South American regional studies, but it was a lot different from what I’d been anticipating, and I ended up dropping out.”

“In 2004, I re-enrolled in a master’s program at the University of Salamanca in northern Spain with a scholarship from the Spanish government. During my doctoral program in 2008, I traveled to a barrio [poor neighborhood] in the Venezuelan capital of Caracas for field research. All of a sudden, I fell seriously ill, and I happened to encounter Cuba’s international medical brigade. I received free treatment and was able to write my paper. More than anything, the doctors in the brigade had a sense of mission, the belief that they are doing something honorable.”

The international healthcare solidarity between Venezuela and Cuba began in 2003 with the Hugo Chavez administration’s Mission Barrio Adentro (“into the neighborhoods”); today, over 20,000 Cuban physicians are reportedly working in healthcare blind spots in poor urban neighborhoods and agricultural communities.

In 2012, Jeong earned a doctoral degree in social anthropology from the University of Salamanca with a study on Venezuela’s resident councils, which are autonomous organizations of residents. She returned to South Korea, where she worked as a research professor at Korea University. In 2014, she was working as a researcher at the South Korean embassy in Guatemala when her father passed away, prompting her to return and settle in South Korea to look after her widowed mother. That same year, she began working as a research professor at the Busan University of Foreign Studies. But in the summer of 2018, she embarked once again on a “new challenge.”

“For close to 20 years, I had been mainly researching things like social movements, class struggle, social inequality, and the social structures of poverty in Central and South American regions like Venezuela, Mexico, Guatemala, and Cuba, but I sensed that there was only so much I could achieve studying them from the perspective of an observer and outsider,” she recalled. “I was in kind of a research slump. I wanted to build my ability to practically support local residents in their lives like the members of Cuba’s brigade.”

Jeong is one of four South Koreans currently enrolled at the Medical University of Havana.

“Tuition for international students is around 10 million won [US$8,559] per year. It’s free for scholarship students from vulnerable demographics in Central and South America, but they have a social volunteering requirement,” she explained.

“The focus is on preventive medicine and social medicine, so there’s an emphasis on communication between students and professors, between students and other students, and between students and communities. From your first year in medical school, you take time from classes to do weekly practice at neighborhood hospitals known as polyclinics and local treatment centers known as ‘consultorios.’”

Prioritizing the patient above everything elseJeong added that she truly sensed the meaning of “character education” and “prioritizing the patient” during full-scale COVID-19 testing of communities just before her return. One of the professors talked specifically about the importance of facial expressions. “Smile. Don’t act nervous,” the professor said. “The patients will only feel at ease when the doctor appears comfortable.”

Cuba’s family practitioner system

According to World Bank figures, Cuba has the largest number of doctors per capita in the world, with 8.4 per 1,000 people as of 2018. That large number of physicians serves as the basis for a “family practitioner system,” where disease prevention and health management are the responsibility of primary care physicians who regularly tend to families within their region.

All individuals who test positive for COVID-19 are housed at government quarantine centers for treatment.

“Since Cubans always get to see the same doctor when they visit their village clinic under the family practitioner system, they weren’t freaked out at all about COVID-19. The system is stable because med school students focus on what area they want to specialize in and lack a sense of privilege, the idea that they deserve high wages as members of the elite. I think that the essential lesson of the COVID-19 pandemic is that we need to have a social system that guarantees equal rights to protection from the common enemy of the coronavirus, without anyone being left out. Even if a vaccine were developed right away, it would be out of reach of the majority of people if a single country or firm were to monopolize its supply.”

Jeong plans to return to Cuba as soon as the airports there reopen. But her ultimate goal isn’t getting a medical license. “I want to become an ‘action anthropologist’ so that I can use my medical skills to engage in meaningful communication with the locals and take part in grassroots social movements,” she said.

By Kim Kyung-ae, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0512/3017154788490114.jpg) [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks![[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’ [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/5217153290112576.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’- [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

Most viewed articles

- 1Seoul’s plan to adopt SM-3 missiles is like wanting a sledgehammer to catch a fly

- 2[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- 3[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- 4Yoon rejects calls for special counsel probes into Marine’s death, first lady in long-awaited presse

- 5Korea poised to overtake Taiwan as world’s No. 2 chip producer by 2032

- 6Yoon voices ‘trust’ in Japanese counterpart, says alliance with US won’t change

- 7US expert says THAAD can’t distinguish between real and decoy warheads

- 846% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 9S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 10‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis