hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Where did all the water on Mars go?

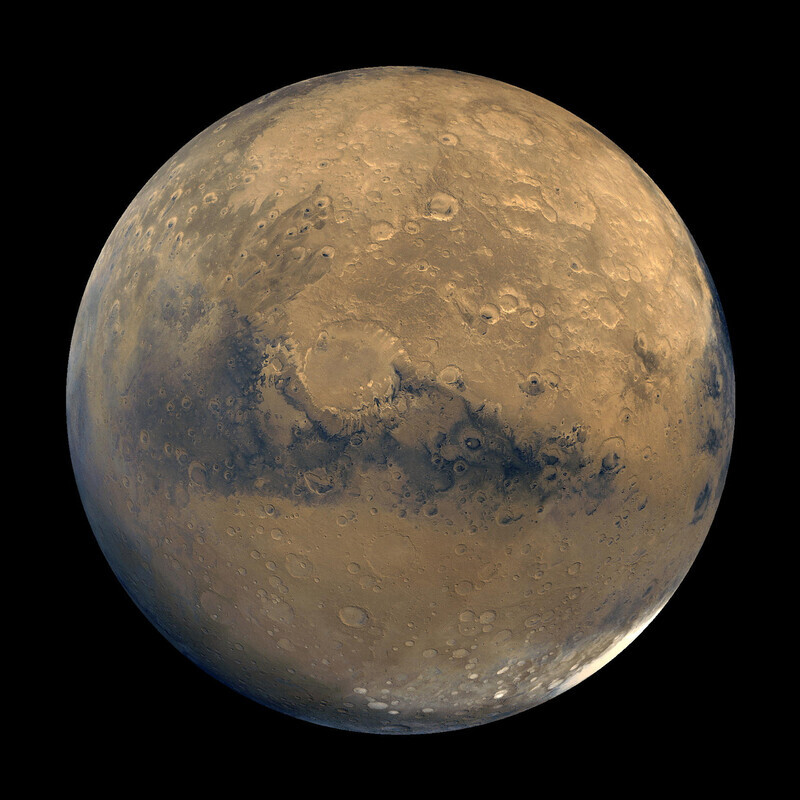

Scientists believe that four billion years ago, Mars had enough water to form lakes, rivers and seas just like Earth. Analysis based on the geological evidence obtained to date suggests the amount of water back then would have been enough to cover the entire planet of Mars to depths of anywhere from 100 to 1,500 meters — roughly half the water in the Atlantic Ocean.

But today, there is no water to be found on Mars’ surface. There is only observational data suggesting a very small amount present in ice form beneath the surface of the planet.

Where did all the water on Mars go?

The most plausible current hypothesis to answer this unsolved riddle is “atmospheric escape,” meaning that the water essentially flew off into space.

According to this hypothesis, as Mars approached the sun, the effects of rising surface temperatures and dust storms on Mars caused water to evaporate, rising to the atmospheric layer where it leaked out in space, unshielded by a magnetic field like the one that exists on Earth. The problem is that this hypothesis isn’t adequate to entirely explain how so much water was lost.

As the Mars rover Perseverance prepared to go to work, scientists with the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) ventured the possibility that water may lie hidden underground on Mars. In new research findings, they shared their speculation about how much there might be.

Estimated 30-99% of surface water trapped in minerals

Published on March 16 in the international journal “Science,” the researchers’ hypothesis was based on computer simulations using data gathered from Mars orbiters, Mars rovers and meteorites, along with studies of the chemical composition of Mars’ current atmosphere, particularly the ratio of deuterium and hydrogen.

Water molecules are made up of oxygen and hydrogen, but not all hydrogen atoms are alike. Most hydrogen atoms have a nucleus containing a single proton, but a very small proportion — roughly 0.02% — have both a proton and a neutron in their nucleus.

This type of isotope is called deuterium. Regular hydrogen atoms without nuclei would escape Mars’ gravitational pull far more easily than heavier isotopes. As a result, more deuterium would be left behind in the Martian atmosphere.

But researchers said the current ratio of deuterium in Mars’ atmosphere is not enough to fully explain the amount of water lost due to atmospheric escape.

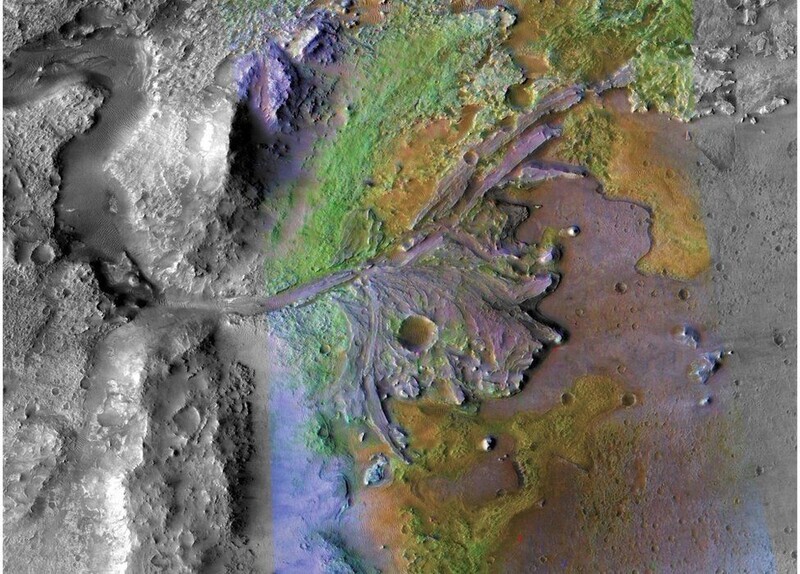

Another water-removing mechanism that they focused on was the trapping of water inside of minerals distributed through the crust of Mars.

When water meets rock, a chemical weathering reaction occurs, forming clay and hydrous minerals.

A hydrous mineral is a structure in which water molecules are present inside of mineral crystals. On Earth, amphiboles and zeolites are examples of hydrous minerals that arose due to this kind of chemical reaction.

But with the prolific crustal activity on Earth, older parts of the crust are constantly being dissolved into the mantle, forming new crust at the boundaries of tectonic plates. This results in a cycle, as water and various other molecules are released once again into the atmosphere through volcanic activity.

But Mars has no tectonic plates causing crustal deformation. Once the surface dries up, that’s it.

According to the researchers, the computer simulations showed that anywhere from 30% to 99% of the early water on Mars may be trapped in minerals within the crust. The reason for such a wide range of estimates is the current lack of sufficient information about the water content of Mars’ crust.

Mars already a wasteland by three billion years ago

“The hydrated materials on our own planet are being continually recycled through plate tectonics,” explained Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA’s Mars Exploration Program.

“Because we have measurements from multiple spacecraft, we can see that Mars doesn’t recycle, and so water is now locked up in the crust or [has] been lost to space,” he added.

With this atmospheric escape and weathering of the crust, Mars had transformed into the barren wasteland of today by anywhere from one to three billion years ago, scientists estimate.

Eva Scheller, a Caltech doctoral candidate in planetary geology who served as lead author for the paper, said the history of hydrated minerals in the Martian crust definitely dates back over three billion years.

This means that before that, Mars would be suitable for life, she added.

To identify evidence of life, the Mars rover Perseverance — which marked the one-month anniversary of its arrival on Mars last March 18 — would need to locate and collect hydrated minerals that are more than three billion years old.

By Kwak No-pil, senior staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 346% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 4[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 5‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 8[Interview] Dear Korean men, It’s OK to admit you’re not always strong

- 9Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 10[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far