hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

S. Korea’s delayed jump into space and the challenges that lie ahead

Due to the incomplete nature of its initial launch, celebrations for Nuri’s success have been postponed until next year. But that hasn’t changed Korea’s blueprint for space development.

The global space race has become an irreversible trend. Money flowing into the space industry has been increasing rapidly since the 2010s. According to the venture capital firm Space Capital, private investment in space companies exceeded $10 billion in the third quarter this year. Prior to this, the record high was US$9.8 billion, set last year.

This coincides with the lifting of restrictions on Korea’s space development. These restrictions were part of a 1979 South Korea-US missile guideline agreement that imposed limits on launch range and payload weight. This agreement expired in May.

Reflecting this change in circumstances, the government revised the Third Master Plan for Promotion of Space Development in June. The plan prioritizes the reliability of the Nuri rocket. Reliability is a key issue as 10 out of the 114 rockets launched worldwide in 2020 failed. This is why 680 billion won (US$581 million) has been invested in four repeated launches.

In order to launch a lunar probe with the Nuri rocket, upgrades in its performance are necessary. Although Nuri has the ability to send a small payload of 500 kilograms to the moon, experts point out the inevitability of developing a new projectile to be able to send a moon lander to perform exploratory functions. However, in a preliminary feasibility study in June, the plan to improve the engine performance of the Nuri rocket was postponed.

The government is considering adding a solid propellant kick motor to the tip of the Nuri rocket as an alternative. It’s been calculated that a lunar probe can be sent into low-Earth orbit with the Nuri and then propelled into lunar orbit with a solid kick motor. The Nuri rocket’s future will depend on which direction the space program chooses.

The development of solid fuel projectiles, which was stalled during the 1979 missile guideline agreement, has resumed. The government intends to develop small solid fuel projectiles by 2024. Solid fuel rockets are simpler in structure than their liquid fuel counterparts such as the Nuri, and allow for low-cost, short-term launches.

In consideration of this, the government has decided to promote the development of solid fuel rockets backed by private companies. Professor of aerospace engineering at KAIST, Ahn Jae-myung, notes, “In the future, in order to satisfy diverse demands, we need to establish state-backed high-performance rockets such as the Nuri as well as smaller projectiles developed by private companies.”

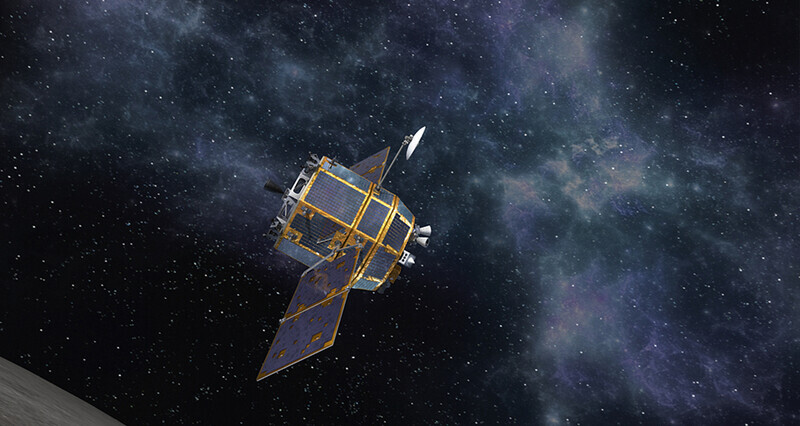

After several delays, lunar exploration is expected to commence next year. First, the Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter will be launched off a SpaceX rocket in August next year. After entering lunar orbit by the end of next year, the probe will orbit 100 kilometers above the surface of the moon and conduct exploration activities for a full year. Assembly of the 678-kilogram lunar orbiter is expected to be completed by the end of this month.

While Korea was concentrating its efforts on developing the Nuri rocket, the international space industry has changed significantly. Instead of governments, private companies are spearheading the new space era by combining space technology with industry. We’re entering an era where space development prioritizing low cost and high efficiency has become an indicator of systemic and national competitiveness.

Currently, the biggest topic in the international space vehicle launch market is reusable rocket technology. Reusable rockets significantly lower costs. SpaceX, unrivalled in terms of advanced technology, has recorded 100 instances of first-stage rockets being recovered for reuse. One rocket can be launched 10 times. First-stage rockets account for 60% of the total rocket launch cost. Because of the low cost, reusable rocket technology accounts for 20% of the global rocket market. China is independently developing reusable rocket technology as is Japan, in collaboration with Germany and France.

Korea has secured the technology, but with no tangible success to go along with it, it still has a long way to go. The Nuri is a medium-sized rocket that performs better than its predecessor the small-sized Naro. However, compared to the main rockets of the major countries in the space industry, the Nuri comes up short at one-tenth the size.

Another hot topic is the development of rockets for the small satellite market. With the development of miniaturization technology, the demand for launching small satellites weighing less than 500 kilograms is rapidly increasing. In particular, the construction of communication networks by utilizing low-orbit satellite clusters has become a hotbed for competition in many countries. Market research firms predict that the space market will grow from US$2.8 billion in 2020 to US$13.7 billion in 2030.

In Korea, however, even if private companies develop small rockets, there are currently no launch pads available. As such, the government first plans to build a private launch site for solid-propellant rockets at the Naro Space Center by 2024.

These developments will pose new questions for the future of Korea’s space policy. A successful Nuri rocket launch next year will herald the completion of the first stage of Korea’s space infrastructure. After the launch, the priority will be on the efficient use and improvement of this infrastructure in consideration of global trends.

Hwang Jung-a, a senior researcher at the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute, remarks, “The history of space development in Korea will be marked as either being pre-Nuri or post-Nuri.”

“In the post-Nuri era, we will set goals and have a clear vision before working on the technology to fulfill these objectives,” Hwang continued.

By Kwak No-pil, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 1Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 2Trump asks why US would defend Korea, hints at hiking Seoul’s defense cost burden

- 31 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 4[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- 5Fruitless Yoon-Lee summit inflames partisan tensions in Korea

- 6[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 7[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 8Bills for Itaewon crush inquiry, special counsel probe into Marine’s death pass National Assembly

- 9[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 10At heart of West’s handwringing over Chinese ‘overcapacity,’ a battle to lead key future industries