hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Sex, screen and sports: How Chun Doo-hwan’s plan to distract the public backfired

Memories of the Gwangju massacre were more than a thorn in the side of Chun Doo-hwan, they were something that needed to be erased.

It was no coincidence that then-Blue House press secretary Heo Mun-do scheduled the start of the massive Gukpung 81 festival to fall 10 days after the first anniversary of the Gwangju Uprising. The festival featured singing contests and theater competitions, an academic forum, and exhibitions of traditional arts such as nong-ak farmers’ music, talchum mask dancing and archery.

Gukpung 81 had international food stalls and performances by top musicians such as Cho Yong-pil and the Great Birth, Shin Jung-hyeon and Music Power, Song Chang-sik, and Kim Chang-wan. A Seoul National University band won the grand prize at its singing competition, in which 6,000 students in 250 clubs representing 197 universities across the country participated.

The government had manufactured this event in order to be remembered as having put on a world-class festival and to shift public attention away from politics.

Ironically enough, Chun — a man who rather than seek legitimacy for his rule, began it with a massacre — brought about diverse changes to Korean culture. He intended to distract the people by implementing a policy known as the “Three S’s” — sex, screen and sports — which involved establishing professional sports leagues, easing censorship in extra-political domains, and lifting the nighttime curfew.

This plan did not go as intended, however. Relaxing these strictures did not make the populace complacent or docile, but rather whetted their appetite for freedom and democratization.

It seems that the masses are not so foolish as to follow their government’s lead without question, but neither do they always make the right choices. While it is true that they can fall off course and even bring about their own calamities, sometimes their decisions go on to make history.

Chun’s policy changes became apparent when the nationwide curfew was lifted in January 1982. With the curfew gone, a whole culture sprang into being as people began to enjoy leisure after dark. Late-night coffeehouses and soju tents popped up, and late-night movie screenings and sightseeing became widespread.

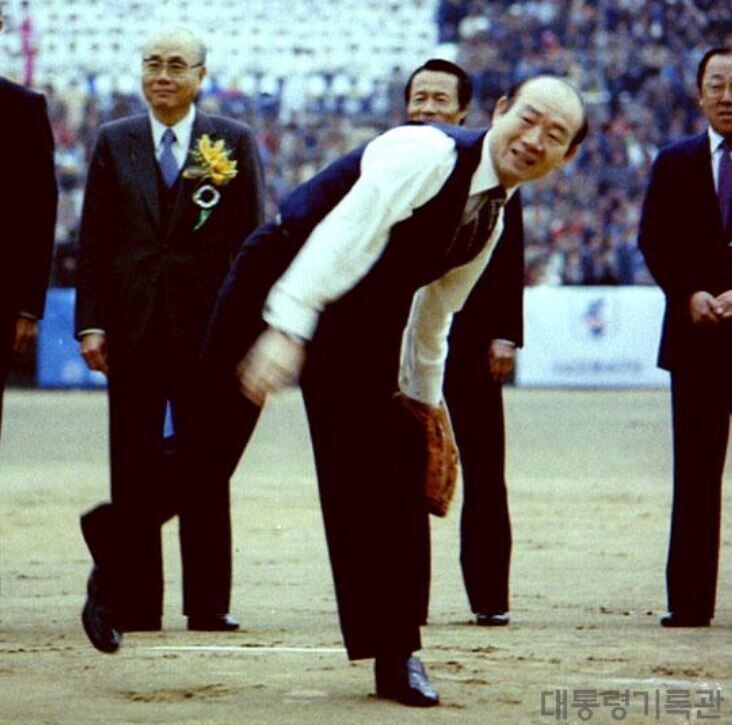

Korea’s professional baseball league, the KBO, was launched on Dec. 11 of that year, after which came the professional soccer league and investments in large-scale basketball tournaments and professional Korean wrestling, known as ssireum. Chun’s No. 2, Roh Tae-woo, was appointed minister of sports, and plans were carefully laid for the Asian Games in 1986 followed by the Summer Olympics in 1988.

Hitler used hosting the Berlin Olympics in 1936 as a form of cunning propaganda intended to create a false sense of unity and whitewash his dictatorship. In the same vein, Chun’s regime in Korea promoted professional soccer and basketball so that the people would refocus their attention to sports. It is possible that Chun’s personal love of soccer may have been a factor as well.

The Chun regime also gave the film industry more freedom. Small theaters were allowed to open, and censorship was eased to an extent. Under the Park Chung-hee administration, film studios had taken part in a licensing system. According to the terms of the revised Motion Picture Law enacted in 1973 in the wake of the Yushin Constitution, anyone establishing a film studio was required to put down a deposit.

Licenses acquired previously were annulled, and only 12 companies that reregistered under the new rules were permitted to operate. A film studio was given the right to import one foreign movie for every three movies it produced. This law was not intended to promote local films, but rather to tighten control over the film industry. Censorship was also extreme, and the representation of social problems and real-life events was forbidden, as was political content.

Chun ordered the promotion of the film arts in 1984, and the Motion Picture Law was amended in 1985. The licensing system was changed to a registration system, and small-scale production companies were allowed to make films. According to an article appearing in Hankyoreh on Sept. 23, 1989, 69 production companies had been formed as of 1988, and 18 more were added in 1989. Censorship remained an issue, but by this point, a legitimate pathway had opened for multiple filmmakers to produce diverse movies. From the mid-80s, independent film organizations and works were beginning to emerge.

Despite this development, the Korean films most identified with Chun’s regime are erotic films produced in keeping with Chun’s Three S’s policy.

It is worth considering that as censorship intensifies, there is only a narrowing range of material available for use in a mainstream motion picture. Social criticism must be conveyed metaphorically, with a trend towards the depiction of personal, private scenes. This meant that even in the 1970s, before the erotic blockbuster “Madame Aema” rocked Korean society in 1982, so-called “hostess movies” such as “Heavenly Homecoming to Stars” (1974), “Young-ja’s Heydays” (1975), and “Winter Woman” (1977) were in vogue.

The Yushin period under Park Chung-hee was essentially a dark age for Korea during which everything was suppressed — if a song were even slightly melancholy, it would be banned under the pretext of being decadent and undermining public order, and any explicit representations of sex or violence were strictly forbidden.

The irony being, of course, that even as the regime made the hypocritical demand that people live morally and frugally, Park and other members of the ruling class enjoyed illicit pleasures in high-class restaurants, and the Korean Central Intelligence Agency violently cracked down on innocent people.

In this regard, Chun’s actions were transparent and his demeanor childish. He allowed the proliferation of sports and entertainment but took violent action if anything threatened his grip on power.

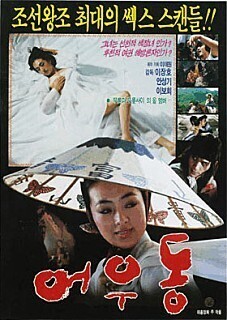

In the 1980s, a glitzy, frivolous spirit prevailed worldwide, and the Three S’s policy happened to capture it quite well. As compared with the Yushin period, Chun allowed relative freedom in the sports and entertainment industries. A wave of adult films followed up the release of “Madame Aema” (1982). In 1982, 35 out of 56 Korean movies were classified as adult films, a proportion which rose to more than 60 out of 80 in 1985. But even this genre boasts its share of masterpieces, thinking back on such titles as “Between the Knees” (1984), “Mulberry” (1985), “Eoh Wu-dong” (1985) and “Daengbyeot” (1985).

When censorship is eased, more space opens for thought and imagination. The boom in adult films at the time was also linked to the growth of the videocassette market, which was dominated by adult video series such as “Mountain Strawberries,” “Red Cherry” and “Night Market.”

The Chun administration attempted to loosen the reins on sports and popular culture and impose a state-controlled national culture. But his efforts were rife with contradictions. People were given freedom but banned from crossing certain lines, and the same government that promoted national culture suppressed the national culture of the universities and the political opposition.

One infamously ludicrous incident occurred when the producers of “Madame Aema” used the homophonous character for “hemp” in the title instead of “horse” following objections from the censors. Wouldn’t a cannabis lover have been more subversive than a lover of horses?

The activists who were pushing for Korea’s democratization also advocated a culture that stresses Korean national sentiments and reflects Korean reality through national literature, national films, and the public folk theater of madangguk. So while the two sides were using similar language about “freedom” and the “Korean nation,” their goals and subject matter were bound to be different.

But the fundamental objective of the Chun administration’s cultural policy was keeping the public in the dark. It was evident that Chun was trying to divert public attention away from politics.

Chun may have been hesitant to sustain the regime with the same methods as his predecessor Park Chung-hee given public hatred for Park’s Yushin regime. Chun would have resorted to any method to prop up a regime he’d instituted through a coup and a massacre.

But while Chun may have basically stuck to the formula of the Three S’s, there was no guarantee the public would follow the script. Democracy protests finally made strides in June 1987, power changed hands ten years later, and institutional democracy was implemented.

So perhaps it would be more accurate to say that both policy and the world were transformed by the demands and changing attitudes of the masses. Korean culture’s huge impact on the world today can also be traced back to the achievements of democracy.

By Kim Bong-seok, pop culture critic

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 9[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 10[Editorial] Government needs to stop impeding Sewol mourning