hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

S. Korea faces a labor shortage of its own, but for different reasons than the US

In a Nov. 26 report, the Financial Times cited the labor supply as one of the reasons that inflation isn’t as severe in Asia as it has been in the US and Europe. The article said the region has suffered less of a shock from the pandemic, which has also spared it from the kind of labor shortage that’s driving up wages elsewhere. Indeed, South Korea’s labor market has nearly returned to its pre-pandemic level.

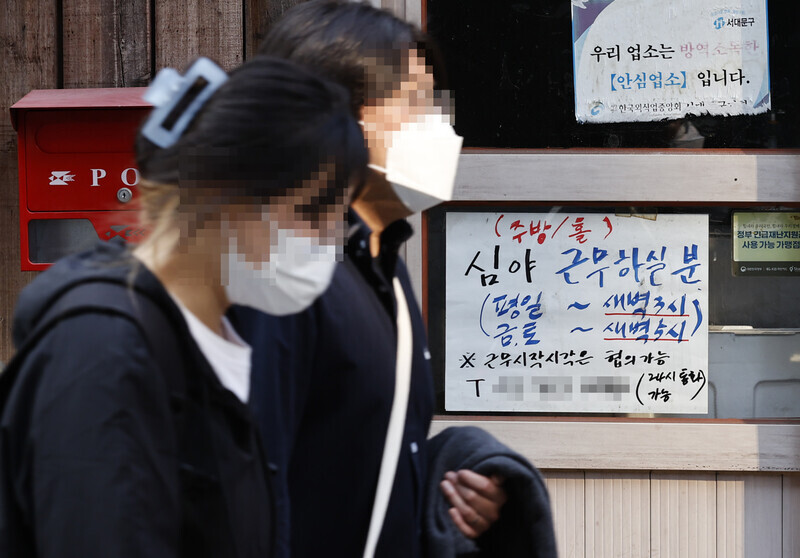

But recently, something unusual has been taking place in some parts of the in-person service sector, including lodgings and restaurants: it’s getting harder to find workers.

“My son has been helping out because I haven’t been able to hire an employee for a month now,” said the proprietor of a coffee shop in Seoul’s Songpa District who asked to be identified by the surname Lee.

Is Korea on the verge of a labor shortage, too?

An analysis of microdata provided by Statistics Korea shows that while Korea isn’t facing the same kind of across-the-board labor shortage as the US and other countries, a shift in jobs among people in their 20s and 40s, whose employment situation had been poor even before the pandemic, is causing a labor shortage in some parts of the economy.

Korea’s labor market is different from that of the USOverall employment indicators strongly suggest that Korea doesn’t have the kind of labor shortage being seen in other countries. Comparing figures from Statistics Korea with those from the Department of Labor in the US, where the labor shortage is most severe, we find that there were 148,611,000 nonfarm payroll workers in the US last month, which was still 3,147,000 fewer than before the pandemic, in November 2019 (151,758,000).

But in October, Korea reported 27,741,000 employees — an increase of 232,000 from October 2019 (27,509,000).

Americans have been dragging their feet about returning to the labor market. The labor force participation rate in November 2021 (61.8%) was lower than in November 2019 (63.2%). That contrasts with Korea, where the labor force participation rate in October 2021 (63.2%) was almost the same as two years earlier (63.6%).

The primary reasons for the labor shortage in the US are believed to be early retirement by elderly people worried about catching COVID-19 and the slumping labor market participation rate of women, who have been forced to shoulder a larger share of childcare as schools have closed.

The labor market participation rate for those aged 55 and above last month was 38.4%, a full two points below November 2019 (40.4%). The labor market participation rate for women also decreased 1.5 points (59% to 57.5%) over the same period.

But in Korea, the opposite has occurred. The labor market participation rate for those aged 60 and above is at 45.7%, which is higher than in October 2019 (44.4%). The labor market participation rate for Korean women is at 53.8%. While that’s lower than the pre-pandemic rate of 54.1%, it’s still just a 0.3-point drop, considerably less than in the US.

A job transition for people in their 20s and 40sGiven the aggregate figures in the labor market, therefore, it doesn’t appear that Korea is dealing with the kind of labor shortage in which economic players stay out of work. So why are businesses having a hard time getting help?

When Hankyoreh reporters analyzed the number of employed people per industry in each age group using microdata from Statistics Korea on Tuesday, they found that the number of employees in the lodging and restaurant sectors in October 2021 was 205,000 lower than in October 2019, prior to the pandemic. The biggest decrease was seen among people in their 20s, at 81,000, followed by people in their 40s (66,000), 50s, (59,000), 30s (25,000) and teens (21,000). Among people aged 60 and above, the number of employees in these sectors rose by 47,000.

In contrast, the industries in which the number of employees in their 20s and 40s has surged in recent months are transportation and warehousing, which include food and parcel delivery and related jobs in logistics. Jobs in those areas have increased by 190,000 between October 2019 and October 2021, with the most-represented age groups being people in their 40s (54,000 new jobs) and 20s (45,000 new jobs).

The job shortage in the US has also been heavily felt in the in-person service industry, including restaurants, entertainment and hotels. But Statistics Korea’s microdata shows that a somewhat different trend is presenting itself in Korea. This isn’t an avoidance of jobs over concerns about infection, but rather a shift in jobs from one sector to another. Analysts assume that the shift is taking place among people in their 20s and 40s, whose employment situation was already more vulnerable than other age groups even before the pandemic.

The unemployment rate was close to 10% among those in their 20s at that time, and corporate rounds of hiring became even scarcer after the outbreak of the pandemic. At the same time, part-time work in the in-person service sector, including restaurants and lodgings, started to dry up.

Those workers appear to have migrated to the platform economy in that process.

Workers in their 40s, who make up the bulk of the economy, have had so much trouble finding work that President Moon Jae-in even set up a task force to tackle the problem after taking office.

People in their 40s have been hit hardest by a sluggish manufacturing sector and by restructuring in the self-employed sector. Over the course of one year after the pandemic began (August 2020 to August 2021), the number of people in their 40s running small businesses with employees decreased by 34,000, which was the biggest reduction among all age groups.

Considering that the number of self-employed individuals in the transportation and warehousing sectors has been increasing, it’s possible that some people in their 40s who had been running small hotels or restaurants have now moved to the platform economy.

“We appear to have a partial labor shortage, rather than a total labor shortage as in the US,” said Oh Min-kyu, head of Haebang (meaning emancipation), a research institute focused on labor issues.

“There had already been a bottleneck in employment opportunities for young people even before COVID-19. Then when even the low-quality service sector jobs that had been relatively accessible moved out of reach in the pandemic, [young people] seem to have moved to platform labor. It’s possible that people in their 40s are moving away from self-employment,” Oh added.

Flexible but unstable jobsIf the labor shortage in Korea is due to a shift in jobs between sectors of the economy, Korea is still unlikely to face the inflationary pressure of rising wages as the US has seen. Instead, this leads to worries of another sort: the quality of employment. People in their 20s and 40s have moved from low-quality service sector jobs to unstable platform work where they find themselves straddling a gray area between workers and entrepreneurs.

“A backlog of issues including youth employment have collided with the growth of the delivery market and the outbreak of COVID-19, which seems to have led to a shift in jobs. While platform labor can have flexible working conditions, it still can’t be regarded as good work. We’ll have to wait and see whether the shift in jobs continues,” said Nahm Jae-wook, an analyst at the Korea Research Institute for Vocational Education and Training.

By Jun Seul-gi, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 7Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 8[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be