hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

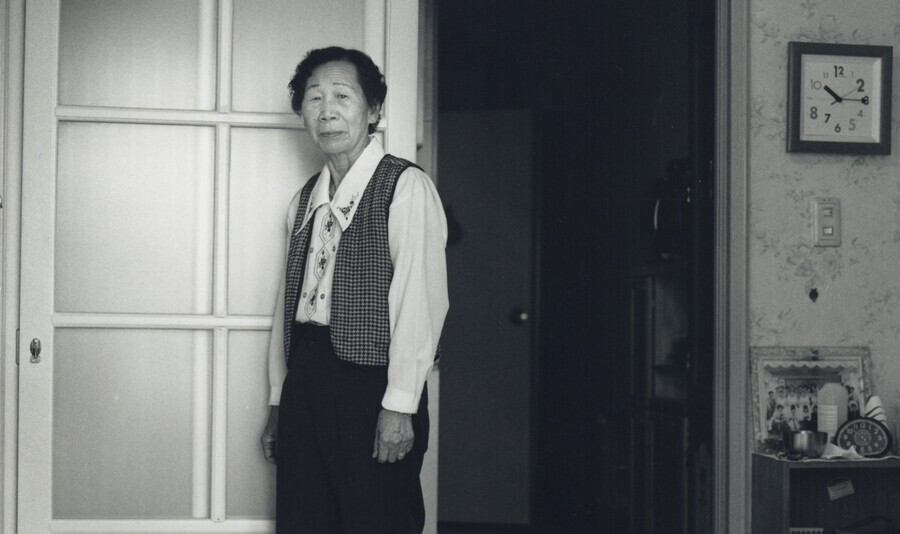

Holding space for “comfort women” survivors’ multifaceted lives, victimhood

The woman Koreans know as Kim Sun-ak, a survivor of the “comfort women” system of sexual enslavement practiced by the Japanese imperial army during World War II, was called by countless names: Kim Sun-ak, Kim Sun-ok, Walpae, Sadako, Deruko, Yoshiko, Matsudake, comfort woman, courtesan, madam of the brothel, housekeeper, mom, granny, mad dog, wino, gangster granny, and Ms. Sun-ak.

Kim was born in Gyeongsan, North Gyeongsang Province, in April 1928 under the lunar calendar. She endured many trials and tribulations before passing away at the age of 82 in 2010.

Kim’s family was “the poorest in the village.” Though her family called her Sun-ok, when her father went to register her birth, the township official wouldn’t let him use the character for “ok” in her name. The official’s explanation was that “that kind of name [was] for girls with pedigree.” That’s how Sun-ok became Sun-ak.

When she was 16, Kim left home with a neighborhood uncle to get a job at a sewing thread factory in Daegu. This was to avoid the Japanese empire’s forced drafting of unmarried virgins. For the first time in her life, she got on a train and said goodbye to her hometown. But where she arrived was not a factory but a human trafficking agency that aided the operation of the Japanese military’s “comfort stations.” She had been scammed into being forcibly drafted into the Japanese military’s system of sexual slavery.

From Gyeongsan to Daegu, from Daegu to Seoul, then to Harbin, Qiqihar, Beijing and Zhangjiakou — Kim was hauled to distant, faraway places. Her name changed four times — to Sadako, Deruko, Yoshiko and Matsudake — before the war ended. When she returned to her liberated homeland, there was not much she could do with an “already ruined body,” to borrow her expression.

So, Kim worked as a gisaeng courtesan in the red-light district to make a living, then became a “mamasan” madam who sold women in US military camp towns. But she never mentioned any of the stories from these times during official appearances at events where she testified as a victim of the “comfort women” system. This was because doing so would have been unacceptable during those times.

The erasure of life beyond the paradigm of victimhoodWould it be possible to accurately reproduce the lifetime of a “comfort women” victim in popular culture? More specifically, would Korean society accept the circumstances that led these victims to work in the sex industry after returning home? This has been a lingering question for some time.

Since the mid-2000s, Korean pop culture has represented “comfort women” victims as either innocent victim-girls or grandma-activists in old age who shepherded a worldwide movement of peace while erasing the survivors’ middle age from popular narratives. Korean society didn’t ask how the girl became the grandma, or what kind of difficulties these women suffered during that process after coming home — nor did popular culture try to imagine them. That in-between time of bitterness only existed as shadows in the regretful hearts of “comfort women” survivors, now in their old age — just like the grievances murmured by Na Ok-bun, played by Na Moon-hee, in front of her mother’s grave in the movie “I Can Speak” (2017).

Imagining “comfort women” victims’ 20s to 50s wasn’t always taboo. From the 1970s to the ‘80s, narratives and images related to the Japanese military’s “comfort stations” were sometimes provocatively portrayed in fiction and film, and in 1992, when the “comfort women” issue finally started to become known thanks to the courageous testimony of Kim Hak-sun, the popular drama “Eyes of Dawn” had its protagonist Yoon Yeo-ok, played by Chae Shi-ra, appear as an “eroticized adult woman” — an unimaginable character by today’s standard.

In the book “The Donkey Ears of the Powerless” (published by Humanitas), scholar of Korean literature Heo Yoon points out that popular culture’s girl-grandma binary in representing “comfort women” victims became even more entrenched via the mobile photoshoot incident of 2004, in which a famous actress was heavily criticized for doing a “comfort women”-themed photoshoot. The “comfort women” movement in Korea had changed social perceptions on sexual violence through its tireless efforts, leading to such overwhelming criticism.

But an unintended effect of the response was that certain periods within the life cycle of “comfort women” victims became off-limits from popular cultural imagination. While this is inappropriate in and of itself, it’s even more problematic considering that it made it harder for Korea to reflect on its patriarchy.

The political situation was no different. Those deviating from victimhood as defined by the patriarchy were subject to erasure.

Many “comfort women” survivors who returned to Korea and had to do whatever work to make a living became gisaeng like Kim or lived in US military camp towns, but to mention these circumstances of life publicly might bolster those claims of “comfort women” as “voluntary sex workers,” so they remained hidden. The myth of victimhood became a shackle restricting the “comfort women” movement in Korea and pressured not just “comfort women” victims but countless other women to feel shame for what happened to them.

From how daughters of poor families who couldn’t even use the character for “ok” in their names at will being sold off to the Japanese military, to how these women couldn’t live comfortable lives even after suffering through ordeals at the hands of the Japanese military and coming home, the struggles of “comfort women” victims were made possible by the enduring collusion between Japanese imperialism and Korean patriarchy.

The documentary “Comfort” (2020) renders the entire life of Kim on the screen based on the oral statements she left behind and other various records, comforting Kim by each and every name she was called. Then, the film asks viewers to come face to face with times from which popular discourse and diplomatic politics averted their gaze.

Director Emmanuel Moonchil Park said in an interview, “There’s no such thing as a clear-cut, model victim. The same goes for the Japanese military’s ‘comfort women’ victims.” From now on, Korean society must cast an unflinching gaze at the figures we erased. As much as it would be a way to restore the victims’ honor, it would also be a way for Korean society to reflect on the patriarchy that pervades it.

There’s still one thing we must remember. That’s the fact that, regardless of the kind of life Kim lived, we’ve managed to create a rich discursive field on which nothing would contradict the fact of her victimhood. Based on the history of the “comfort women” movement in Korea and the history of popular narratives about “comfort women” in Korea, the documentary “Comfort” was able to take a courageous step forward. The legacy left behind by Kim has become the basis on which we’ve expanded our world by one little step today.

By Son Hee-jung, author and film critic

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 4Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 5BTS says it wants to continue to “speak out against anti-Asian hate”

- 6AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 7Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 846% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 9Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 10Ethnic Koreans in Japan's Utoro village wait for Seoul's help