hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

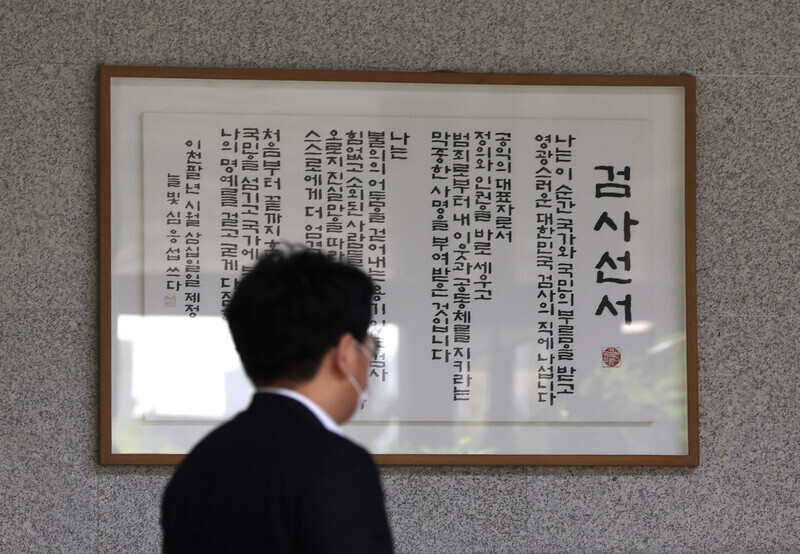

S. Korea’s 68-year debate over investigative authority of prosecutors, police

In 1954, a debate was held at the National Assembly to discuss which one of two agencies, the police or the prosecution service, was at a greater risk of becoming fascist. After the debate, the Criminal Procedure Act was enacted, granting the prosecution service both investigative and indictment powers.

The police’s negative image was a result of the role the police played during the Japanese colonial period in South Korea. At the time, the prosecutor-general, who attended the debate, argued that “theoretically, it is legal to leave investigations to the police and give the prosecutor only the right to indict, but this would only be possible 100 years down the road,” echoing the sentiment of the era. Thus marked the birth of prosecutors’ investigative powers.

The controversy over investigative authority, which had stayed dormant for nearly half a century, came back to the fore in 1999 during the Kim Dae-jung administration. President Kim Dae-jung promised to restore the independent investigative authority of the police, but the plan was halted due to strong opposition from the prosecution service. Similarly, President Roh Moo-hyun launched a consultative body in 2004 to discuss the same issue, but it failed to reach an agreement due to the stark differences between the police and prosecutors’ positions.

In 2011, the Lee Myung-bak administration reached an agreement through talks at the National Assembly to stipulate the police's right to initiate investigations while allowing the prosecution to retain its authority to investigate, but neither the prosecution nor the police were satisfied. The prosecution's collective opposition to the revision of the Criminal Procedure Act, which broke some of the original agreements, led to the resignation of then-Prosecutor General Kim Joon-gyu.

Discussions of prosecution reforms in Korea have mainly centered around two subjects: dispersing the powers of the prosecution — including investigation, indictment, warrant request, and execution of penalty — and securing the political neutrality and independence of the prosecution service.

The framework of the current setup of the prosecution service and police’s investigative authority was created through consultations between the Blue House, the Ministry of Justice (prosecutors), and the Ministry of the Interior and Safety (police) in June 2018 under the Moon Jae-in administration.

The Democratic Party of Korea, which had rushed to set up a body for investigating crimes by high-ranking government officials, handled amendments to the Criminal Procedure Act in January 2020 after controversy over the fast-track procedure in the National Assembly.

The amendments included limiting the prosecution service’s ability to directly initiate investigations to crimes in just six major areas (corruption, economic crimes, crimes of public officials, election crimes, defense industry crimes, and catastrophes), abolishing the prosecutors’ authority to direct police investigations, and granting the police the primary power to end investigations. The new rules went into effect on Jan. 1, 2021, following a grace period.

At the time, the changes affecting investigative powers garnered plenty of criticism. This is because, contrary to its stated goal of separating prosecutors’ investigative and indictment powers, the reforms only removed prosecutors’ primary control over police investigations, leaving prosecutors’ power to directly investigate those six fields of crimes intact.

Prosecutors’ power to direct investigations is seen as an effective means of reviewing the legality and appropriateness of police investigations from the initial stages of the investigation. At the time, Democratic Party lawmaker Keum Tae-sup, a former prosecutor himself, pointed out the importance of the prosecution service’s role in checking and supervising abuse of authority by primary investigative agencies such as the police and guaranteeing human rights.

Citing historical examples and cases in major countries such as the US, the UK, Germany, France, and Japan, he said, “The police have direct investigation rights, and in principle, prosecutors only carry out supplementary investigations into cases referred by the police.”

Few would disagree with the idea that prosecutors’ powers to carry out investigations should be further reduced.

“A monopoly on power was created [within] the prosecution because it carries out and commands investigations and even indictments,” said Han Sang-hoon, a professor of law at Yonsei University. “However, in my view, it will be impossible for the Democratic Party to pass their bill itself as it has many loopholes and problems.”

Even though the Democrats are pressed for time, Han says a “democratic procedure by which they canvass opinions from all walks of life, via a public hearing or otherwise,” is necessary.

The People's Solidarity for Participatory Democracy, which voiced criticism of the Democratic Party’s current legislative drive, proposed a basic stance of abolishing prosecutors’ direct authority to investigate and strengthening the police’s investigative control function. It also suggested “regulation by the prosecution, courts, and citizen participation organizations over the legality and adequacy of police investigations.”

In relation to this, a plan related to the prosecution maintaining the right to investigate and removing its authority to direct investigations has become a topic of discussion in legal circles and civic groups after it was proposed by Prosecutor General Kim O-su. But the Supreme Prosecutors' Office issued a separate statement saying it was not reviewing such an option.

The plan proposed by Kim is similar to the bill proposed by former lawmaker Keum Tae-sup in 2017.

“It appears possible to create a law by which when prosecutors request that the police carry out a supplementary investigation for the maintenance of a public prosecution, the police cooperate [with prosecutors] unless there is a justifiable reason for them not to,” said Ryu Byung-kwan, a professor of law at Changwon University, adding that such a law would be drafted on the premise of the prosecution having the right to request supplementary investigations to maintain a public prosecution.

“However, the expression ‘directing an investigation’ can be seen as a top-down relationship,” Ryu said.

Lee Ho-sun, a professor of law at Kookmin University said the plan “seems to be only half reasonable.”

“It’s right for the prosecution to manage and regulate the overall investigation situation. However, considering the police’s investigative capabilities, the power to investigate the six major crime areas should be left to the prosecution service,” Lee says.

Another high-level official with the prosecution service said they disagree with the Democratic Party’s proposed legislation while adding, “In a broad framework, it is correct to separate investigation and the maintenance of a public prosecution. The biggest problem with prosecutors’ investigations is that prosecutors decide what type of investigations to carry out and which they don’t.”

“An alternative could be to prevent the prosecution service from directly initiating an investigation, and instead leave it open for a supplementary investigation afterwards,” they added.

Besides the Democratic Party, which is calling for the complete abolition of prosecutors’ power to conduct investigations, there is also a hard-line all-or-nothing group within the prosecution service advocating the other extreme of the spectrum: pushing to fully defend the prosecution’s investigative powers.

Another high-ranking official in the prosecution service said, "Even if we try to think about alternatives to block the Democratic Party’s bill, it is difficult to raise different opinions internally.”

By Son Hyun-soo, staff reporter; Jeon Gwang-joon, staff reporter; Kang Jae-gu, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 3Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 4[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 5Historic court ruling recognizes Korean state culpability for massacre in Vietnam

- 6Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 7Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 8[Guest essay] How Korea must answer for its crimes in Vietnam

- 9Story of massacre victim’s court victory could open minds of Vietnamese to Korea, says documentarian

- 10Historic verdict on Korean culpability for Vietnam War massacres now available in English, Vietnames